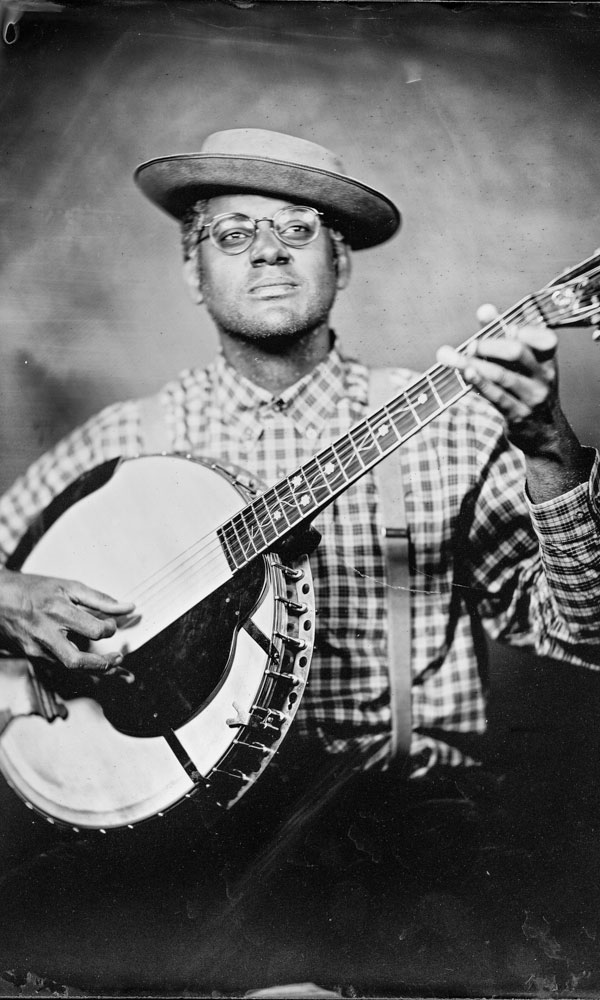

The best word to classify folk singer-songwriter, multi-instrumentalist and musical scholar-historian Dom Flemons (or at least the word he prefers) is “songster,” which in the early 20th century meant someone who could play and sing a wide variety of musical styles. Flemons, whose repertoire covers nearly a century of traditional American tunes, ballads and folklore, is returning to Caffè Lena at 7pm on Thursday, August 30, to play a set of music from his new album Black Cowboys.

Released on nonprofit record label Smithsonian Folkways, as part of the African American Legacy Recordings series, Black Cowboys is a refreshing collection of original and reimagined traditional songs—plus one poem—that examines the history and culture of African-American pioneers in the West.

A founding member of the Grammy Award-winning, old-time string band, Carolina Chocolate Drops, Flemons has been a solo artist since 2014 and was inducted into the Grand Ole Opry as such earlier this year. Black Cowboys has earned rave reviews and was on the Billboard Bluegrass charts for seven weeks. I recently talked with Flemons about the roots of American songwriting.

This isn’t your first time playing at Caffè Lena. Is Saratoga a good town for folk and old-time music?

Oh absolutely. Caffè Lena is one of the sacred venues of folk music. Being a place that’s halfway between New York and Boston, that’s always been one of the things that attracted different performers all the way back to come to Saratoga. And I’m no exception. I find it to be a nice location, and to be able to stand on the stage where so many great performers have stood and played their music is a real honor.

When did your interest in historical, old-time music begin?

When it came to doing music as a profession, I focused on old-time music, folk, blues, early country music, jazz, rock ‘n’ roll and ragtime. And that’s always been part of my musical trajectory from the very beginning. I started out in Phoenix, AZ, and I would busk on the streets as well as do my gigs with an acoustic guitar. And I did that all the way from high school up to college. Once in college, I started to delve into the Library of Congress of field recordings as well as the early recordings made on 78 rpm records. So my knowledge base for music expanded from there.

It seems like the more you dig into American music, the more you find that almost all of these musical genres have African roots. Is that what you’ve found?

You know, around 2005, I went to an event called Black Banjo Gathering, a kind of symposium talking about the African roots of the banjo. And that’s when I first became aware that country music and folk and old-time music also have roots in African-American vernacular music. I was inspired by the gathering to pursue this type of music, wherever it might be, and to present it and create awareness through the music that I performed. And that was the same year that I started the Carolina Chocolate Drops; and we had a long run for nine years where we won a Grammy and traveled all over the world.

What inspired you to do an album like Black Cowboys—your interest in musical history or your own personal history?

Being from the Southwest and being someone of African-American and Mexican-American descent, the stories [of African American cowboys] were interesting to me. I was visiting family out West about seven or eight years ago, and I happened to find a book called The Negro Cowboys. One of the main things that this book wanted to convey was that about one in four cowboys who helped settle the West were African American. That was something I had never heard before, and being a fan of cowboy music as well as movies, I saw there wasn’t a ton of African-American representation in those movies and in those books.

You refer to yourself as the “American Songster.” What exactly do you mean by that?

Well, one of the reasons that I took the moniker of “The American Songster” was to be able to place a label on my music that would be fairly open-ended in terms of the material that I presented on stage. A songster, in the 19th century was a book of lyrics of popular songs, kind of like a secular version of a hymnal, and they were very popular. Then in the early 20th century, before the rise of the recording industry, the term took on a new meaning, describing a musician who played a variety of diverse material. The term “songster,” from the first moment I heard it, I knew it was a very powerful word. When I refer to myself as “The American Songster,” it’s not only as a folk musician, but also as a practitioner of all different types of music. And, of course, original songs as well as traditional songs that are reimagined are a big part of that whole process. That’s why I ended up settling on “The American Songster,” so if I did throw in a country number or a rock ‘n’ roll song, it wouldn’t necessarily be out of the scope of what the American Songster can do.

So it’s the job of the songster to bring these old tunes forward?

Yes! And it’s funny that you say “bring it forward,” because that’s originally an expression from the Gold Coast of Africa called Sankofa, a proverb that means “go back and fetch it.” It means to bring all the wonderful parts of the past, the parts you want to retain, and move those into the present or future, moving forward while still retaining those good lessons from the past.