For over a decade, Joseph James DeAngelo, better known as the Golden State Killer, terrorized the State of California, first committing a series of burglaries, before murdering 13 people and raping more than 50 women. DeAngelo wasn’t any old serial killer, though; he had a degree in criminal justice and worked as a police officer, which helped him avoid capture for more than 40 years. And for all intents and purposes, he probably assumed he’d never get caught. When police finally showed up at his front door in 2018, he was the picture of retired bliss: He’d just put a roast in the oven and was more worried about its cooking time than the murderous crime spree that had finally caught up with him.

Last year, a 74-year-old DeAngelo was sentenced to life in prison without parole. And that day came because investigators stumbled upon a groundbreaking new DNA-tracing technique called genetic genealogy (straight genealogy is done on paper–think family tree–while the added “genetic” refers to the use of DNA). Basically, it’s the exact same method that genealogy websites like 23andMe and Ancestry.com have been using to help everyday people track down ancestral data or locate missing/unknown relatives. The only difference is that criminal investigators’ starting point is DNA-laced crime scene evidence, which is then compared against public DNA data records and transformed into a “family tree.” In the case of DeAngelo, a tiny DNA swab from the handle of his car door was matched to DNA evidence taken from one of his victims, whom he raped and murdered in 1980.

As of October 2020, Saratogians and law enforcement agencies alike have had an expert genetic genealogy consultant in their midst, ready to solve family mysteries and cold cases. Veteran criminalist and forensic scientist Tobi Kirschmann, who actually worked on the Golden State Killer case and recently put in time with the New York State Police, has launched Saratoga business DNA Investigations to do just that. Kirschmann is looking for clients who want to solve family mysteries and better their own adoption research. But she’s also looking to partner with local law enforcement agencies to help them utilize genetic genealogy, in house, to identify human remains and potentially solve cold cases. “This field is moving forward like wildfire,” says Kirschmann. “Nobody could have guessed that.” There are two reasons for that, she says: It was impossible to predict how interested people would become in learning about their ancestral profile or whether they had a secret family history; and those companies, like Ancestry.com, that have been making millions of dollars from customers like you and me have, in turn, been pouring millions of dollars into genome-sequencing research, perfecting genetic genealogy and leaving traditional forensic laboratories in the dust. “These companies have been getting really slick at sequencing the genome, and they’re constantly advancing their technology and using different machinery and going really, really fast,” says Kirschmann. “And just by accident, which really first came out with the Golden State Killer case, someone realized that they could use the same exact technique of genetic genealogy to find a person’s killer.”

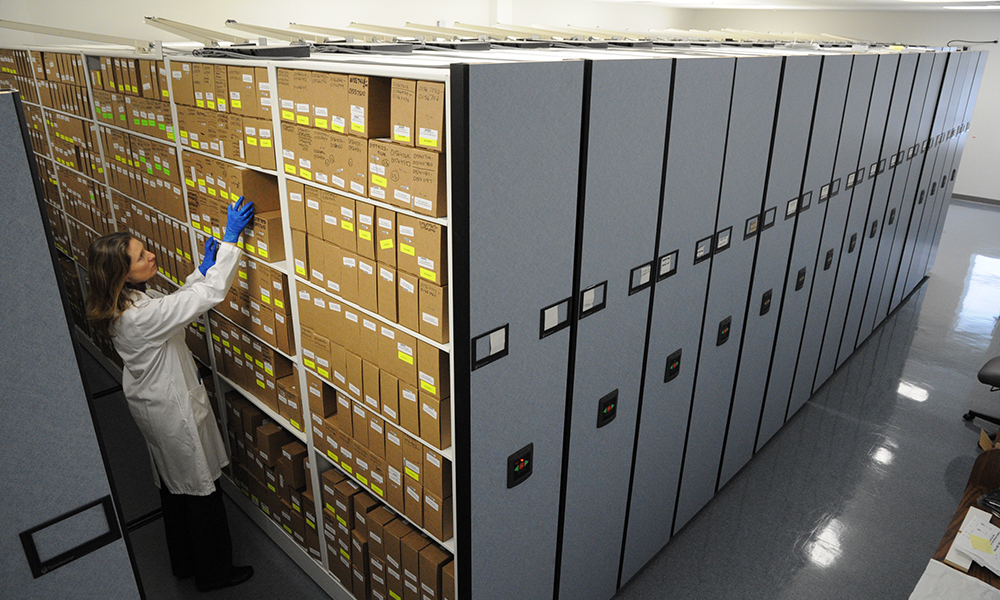

Kirschmann wound up in the trending field in a rather circuitous manner. After earning a bachelor’s degree in women’s studies from the University of California, Berkeley in the early ’90s, she landed a job at a hospital with the hopes of launching a career in medicine or health administration. But when the doctors whom she worked with advised her against the path they’d taken, she switched gears to biotechnology and then forensic science, on the advice of a friend. Though she basically had to start her education over from scratch to become a forensic scientist, Kirschmann worked diligently throughout the aughts, earning first a BS in biology from Humboldt State University and then an MS in chemistry from UC San Diego. While she was working on the latter degree, she accepted a job at the California Department of Justice’s DNA databank in Richmond, CA, the state’s repository for all DNA-related crime scene evidence (think blood spatter or hair samples). She ended up spending nearly a decade there, hence her work on the Golden State Killer case.

“For the last 30 years, every state has been tasked with setting up a DNA bank of profiles,” she explains. “California has done this by getting legally obtained samples from prisoners and felony arrestees.” In New York, on the other hand, any person convicted of a felony or misdemeanor must provide the state with a DNA sample. So, say, someone is arrested for misdemeanor trespassing in Saratoga and gets booked there. His DNA swab, which comes in the form of buccal cells scraped from the inside of his cheek, is then added to a profile in the state database, which also includes his name, date of birth and fingerprints. If his DNA profile happens to match evidence from a murder 10 years beforehand, then, boom! You’re able to potentially solve a cold case. (Per the US Department of Justice, there were some 250,000 cold cases in 2019, and that total has increased by 6,000 every year since.)

Despite genetic genealogy being a potential Rosetta Stone for cold cases, it hasn’t been devoid of controversy. There’s a key ethical question lodged in the practice: Who should own your DNA data, and for what purpose should it be used for? If you’re one of the approximately 50 million Americans who voluntarily paid for and sent in your DNA data to Ancestry.com, for instance, you’ve likely already waived the right to ask such questions. What genetic genealogy companies bury deep in the fine print is that you’re DNA data is basically under their control and can be shared with third parties such as pharmaceutical companies and biotech startups. A recent episode of 60 Minutes shined some troubling light on the subject, noting that a number of those genealogy companies’ prime objective is not helping you find Uncle Joe, but rather harvesting your personal DNA data, which they can then sold to the highest bidder. Also, if those data were to be hacked and fall into the wrong hands—or were simply sold to a foreign investor—there’s no telling what could happen to your most personal information. Identity theft is one thing; now imagine if someone owned your DNA profile.

But at least from Kirschmann’s perspective, the positives of genetic genealogy far outweigh the negatives. “I’m totally OK with every single company having all of my DNA,” she says. “Most people think I’m crazy, but it’s just how I feel.” Of course, there are some people who don’t want anyone other than themselves to have access to their DNA records, and that’s OK, too, she says. “If you feel that way, you might not want to play this game,” says Kirschmann. To try to help locals make up their minds, she’s been teaching a class through Empire State College’s Academy for Lifelong Learning, educating people about genetic genealogy and what goes into the DNA comparing process. Whether you’re in or out, you have to admit that the endgame can be pretty profound: “When you were just innocently curious about the DNA in your family, you had no idea that you could be implicating someone in a crime. You had no idea that you were going to be the missing link that would solve the 50-year-old cold case.”