For Paul “Tucker” Jancsy, a major in the New York Air National Guard and first officer with Delta Air Lines, it had been just another normal work week—if you call flying passenger jets packed full of travelers “normal.” It was March 16, and Jancsy, a Saratoga native, who owns a home up here but flies out of Delta’s New York City hub—which includes LaGuardia Airport and John F. Kennedy (JFK) International Airport, both in Queens, and Newark Liberty International Airport in New Jersey—had just completed an “out and back” from JFK to West Palm Beach, FL, returning to the city that evening and driving up to Saratoga Springs to join his wife, Sara, to spend some much-needed, scheduled time off. That’s when the symptoms started. By March 26, the couple was dialing 911, and Paul was being rushed to Saratoga Hospital with a suspected case of novel coronavirus (COVID-19).

Paul remembers not feeling so hot the week before his hospital admission, but shaking it off as just another late-winter cold. He wasn’t sure where he’d caught it, whether it had been at work or on public transportation down in the Big Apple—”taking the bus to the parking lot just like everybody else,” he wonders out loud. In hindsight, he’d been working in Queens, one of the eventual epicenters of the COVID-19 outbreak downstate, so he practically could’ve contracted the virus anywhere. Symptoms had included some higher temperatures, but nothing that a little Tylenol or a cold shower couldn’t knock out. “I might have let my hubris keep me home a day or two longer than I should have,” he says. “But when you’re a healthy 40 year old, and you do what you’re supposed to do your entire life, ’tis merely a flesh wound, you know?” Things took a decided turn for the worse when Paul lost his appetite and began “fighting for every breath.” That’s what led to the 911 call. “I’ll tell you, I’m glad I was up [in Saratoga],” says Paul. “I was glad I was here.”

What unfolded from there was nothing short of a 28-day waking nightmare. After arriving at Saratoga Hospital, Paul learned that he had, in fact, been infected with COVID-19 and had caught a particularly virulent case of it. He was almost immediately separated from Sara, and from there, eight days after being admitted to the hospital, found himself in critical condition, fighting an infection in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), having been intubated—a breathing tube inserted through his mouth, down his throat and into his airway—and hooked up to a mechanical ventilator, fighting for his life. At that point, Paul’s chances of survival weren’t altogether high—at least on paper. (I’ll get to that shortly.) If you’ve been following New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s daily press briefings, one of the grim data points the governor has repeated time and again has been the fact that 80 percent of COVID-19 patients, who are intubated and put on a ventilator, never get off of it. (New data suggest that that percentage could be even higher.) In other words, patients on ventilators normally succumb to the virus—become those sickeningly high daily death statistics the governor reads off at the top of his briefings. (At last count, 23,144 New Yorkers have lost their lives to COVID-19.) “When I went on a vent, I didn’t realize how low my chances of survival were,” he says. (Throughout our interview, Paul referred to the ventilator as the “vent.”) “I’m glad I didn’t know; the vent-with-COVID survival rate is fairly low as it is. And with the condition that I’d been in, I was much lower. The pulmonologist and I—once I was on the road to recovery and able to understand more—had a discussion about that exact thing. They didn’t give me much [of a chance]—less than 10 percent is a fighting chance, and I’m glad, ’cause it was a fight.”

And fight he did, though, it actually sounds more like all-out war, the way Paul describes it. (Somewhat ironically, he’d actually seen the real McCoy, as a member of the US Air Force, having fought in Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom and the Continuous Bombing Presence Mission.) “One thing with the vent and the drugs, no matter what they had me on, I still fought,” he says, “and I fought and I fought. And I’m proud of this, but they had to physically restrain me to the bed, both legs and both arms, because I was getting physical. I wanted that tube gone; I wanted people away; I wanted to go. I obviously don’t remember that. And then the doctor’s telling Sara that I’m wild and ballistic and fighting every inch. But that fight was driven beyond just me. It was driven for hope for the future.” It was a higher cause, he says, something that eclipsed the condition that he was in. “I was told many times in the hospital, ‘the most stubborn patients get out first.’ And I refused to quit. I refused to quit. Part of that is something I’d like to get out,” he tells me, switching gears from his personal battle to the one waged by others in his name. “This isn’t a story about me, you know? This is the story of a community coming together to fight something that we didn’t know, whether it was the fire department showing up [on March 16], and it was [their] first time with a possible COVID patient; the medics putting on their Tyvek suits and protective gear [to treat me]; being wheeled into an isolation unit in Saratoga Hospital that was set up specifically for COVID, with one nurse in there only, trying to do all the work-ups that, usually, [are done] as a team. And the fear of everything—the fear of me having something communicable, having something that [the hospital staff] hadn’t seen yet and having to do all the testing themselves. [In] the COVID ward and the ICU, the nurses in each were my only line to life. Every day they walked into that building, [and] they didn’t know what they were going to see, they didn’t know who’s coming through those doors, they didn’t know if they were going to catch it and take it back to their families—their sons, daughters, wives, husbands. The sense of community, the sense of ‘we’re going to get through this together, we’re going to beat this.’ [The hospital staff] walked through that building [every] morning wondering if they had a temperature at the door, and they were going to be isolated, or who’s going to be wheeled in by the next ambulance that shows up or the next frantic family in the emergency room with an open car door and someone sick in the backseat. They have done phenomenally well. My friends and colleagues and neighbors and complete strangers have reached out to Sara. We’ve gotten groceries at the door, we’ve gotten food delivered, sometimes anonymously [and] sometimes we figure out who did it.” (One of those do-gooders has been Saratoga Springs Police Department investigator Steven Reside, an old friend of Paul’s, who’s served alongside him in the New York Air National Guard.)

Paul’s fight wasn’t all meted out through blunt force, though. He says he found strength in Sara reading him stories via FaceTime in the ICU, whether it was the ones she’d written about their travels around the world together or the news stories I’d written about him (I’m thoroughly embarrassed that I had to write that last clause, but Paul mentioned it two or three times during our interview). She’d sing him songs and play him music. One day in particular, Sara played Paul a Jimmy Buffett song, “Changes in Latitudes, Changes in Attitudes,” and Paul says he “stopped dead.” “Because that actually drove one of my dreams,” he says. Whether it was from the heavy drugs he was on or just the virus itself expanding his consciousness, Paul clearly remembers dreams in which he was on “islands,” sometimes alone, sometimes not. “I’m able to picture even now what the islands looked like,” he says. “When she played me Jimmy Buffett, it brought me to a Jimmy Buffett resort in the Caribbean. I can’t tell you which one or if it even exists, but in this dream, it did exist.” Paul describes being on a different plane (i.e. level of existence) than his wife, but “the words and the music could still influence me,” he says. “[The song] put me in the resort, not quite healthy and still trying to fight for my way home. And I remember trying to get out of the resort, if you will, and there was no way out, because there were storms coming. I don’t know if there’s something to be said for that, me subconsciously knowing that, hey, it might be sunny and beautiful now, but [the virus is] still after you. You’re going to be stuck there during the worst of it.”

He also found strength from the medical staff at Saratoga Hospital, who cared for him every step of the way—”the nurses talking to me, that would take care of me and everybody that would keep me clean,” he says. Paul didn’t take too well to his feeding tube, so nurses also had to make sure he was getting the nutrients he needed on a daily basis through an IV. “They came and they talked to me,” he says. Making mention of that “other plane” again, Paul says he couldn’t respond back, but that he “knew that salvation was there.” “Without them, I’d be dead,” he says. He takes that a step further: “The doctors kind of take credit for it, right? Because they do what they do to get us, scientifically and medically, to where we are. But without the sustained support from the nurses and the techs, I wouldn’t be here. And I recognize that. When I did wake up and I couldn’t eat, they would come in and feed me. I went to sleep as a guy that could fly supersonic [jets] and I woke up a guy who couldn’t even take a piss on his own.”

But brighter skies were closer than he thought. Paul’s road to recovery officially began on April 13, the day he was extubated and taken off of the ventilator, a little over 10 days after being hooked up to it. “A lot of people, when they’re on the vent, have a lot of issues with speech afterwards, a lot of motor issues,” says Paul. “I didn’t have speech issues. I came out talking, which kind of shocked everybody.” Paul immediately began asking for his family. “There was some gibberish in there as well,” he says. “I asked for ‘Harold’—we have no Harold in the family. We never even had a dog named Harold.” He believes that “Harold” had been one of his mind’s creations, part of the mushroom cloud of hallucinations he had been suffering while on the “nuclear” cocktail of drugs he’d been put on (his doctor’s adjective, not mine). He also asked for a box to put his personal effects in so he could go home. “I asked for Sara…I don’t remember our first conversation,” he says, addressing his wife from across the room. (Sara was present during our entire FaceTime interview, but wearing a mask and socially distanced from Paul, who had his mask off while we talked; his face was gaunt, and he had a bushy red beard, with flecks of gray in it, that he’d grown in the hospital; several times during our conversation, he had to cough, vociferously, the after-effects of the virus still present in his body.) He had been able to communicate with Sara via Saratoga Hospital’s telemedicine network. It was only a day and a half later that he actually realized he was there. “I knew who my family was,” he says, “[and] I knew I had to go.”

For most people who get put on a ventilator in the ICU, things like talking and motor functions come back gradually, through intensive speech and physical therapy. And while it was astonishing that Paul immediately began talking after coming off of the ventilator, it was even more incredible, a day and a half later, when he discovered movement again. “I still remember my first step,” says Paul, triumphantly. “The ICU physician taking care of me thought maybe PT could come in, and we were going to try. So, they come in, and I’ve got a walker—I don’t have one now, which is amazing—and a gait belt, which is a little weight belt that they can grab you from [behind with] so you don’t eat it, and I stood up and I took my first step. It was ungodly painful—it was physically painful, it was emotionally painful. It was emotionally painful, because I knew I could walk—I thought I could walk. I knew I would be able to walk again, but physically, I was like a baby giraffe attempting to stand up for the first time. It knows that it has to stand up and it knows something, but it doesn’t know exactly. Physically, I wasn’t able to take another step. So, they shifted me, and I sat down in a chair. Very painful. The physical therapist in the ICU looked at me and said, ‘In my 15 years of experience, I’ve never seen anybody take a step a day and a half off a vent.’ That motivated me so much. I was going to walk out of that building. I was going to be able to walk again. I’m going to be able to run again. I’m going to be able to play sports again. My second step was having to go back to the bed. I took my second step, I sat down and promptly puked.” And while it was clearly nothing short of a superhuman feat to have taken any steps at all that day, ironically, it was actually the puking that lifted the spirts of the medical staff in the ICU that day. “They were so excited because of the response my body had,” says Paul. “They said your body is responding to pain.” That also marked a major turning point for him—at that exact moment, he felt his emotional pain evaporate. “There was zero sympathy in that room for me,” he says. “There was true hope, and you could feel that. And that was the last time, I decided, that I was going to feel bad for myself. One thing I’ve learned [is that] sympathy doesn’t get me anywhere, sympathy doesn’t get this solved, sympathy doesn’t drive this forward, but empathy does. Everybody’s had struggles; all of our struggles are different. Sara didn’t know the outcome, no one knew the outcome of the vent, and I think that was the most emotional toll anyone could have.”

One particular interaction that Paul had, after recovering enough to be able to carry on a conversation with his care team, stands out. “One of the providers, a pulmonologist named Dr. [Numan] Rashid, said, ‘You have one of the strongest hearts I’ve ever seen.’ And I started laughing and said, ‘Oh, jeez, it’s all those stupid miles [of running] in the Army all of those years ago.’ And then he says, ‘Your kidneys are unbelievably strong as well.’ And then I started laughing and I said, ‘It was probably all of the beers with those same guys running that got my kidneys strong.’ Then he laughed, and I said, ‘We probably should’ve been drinking water.’ But again it goes back to the community aspect of it. If I hadn’t been motivated all those years ago by all of my friends and colleagues, military and civilian, I wouldn’t have had the heart that I had; I wouldn’t have had the kidneys. And [Dr. Rashid] said, ‘You wouldn’t have had the outcome that you did; your chances were so low going in, but you were so ready. You were physically prepared for this.’ Emotionally, [Sara and I] have a very, very good life, and we’re eternally grateful for everything that we have. Delta’s treated me very well, the military’s treated me very well; I’ve had a great adventure. I’ve lived a phenomenal life. And I’ve been ever so grateful in the faith in someone bigger than yourself. I’ve realized that in that hospital, the names I’ve come across, everybody’s different, everybody has a different faith and everybody has the same goal. That faith is unified in strength for us to get better. [The medical staff’s] faith is unified walking through those doors every day confronting what they are. And that’s huge.”

This whole time, of course, Paul’s life was in the balance, but only a choice few times did the word “death” or “dying” come up during our more than hourlong interview. “You know, there was only one time in one of my nightmares and hallucinations [that] anyone said that I was ‘dying,'” says Paul. “I don’t know if they said that around me, and I could hear it, but someone did say that once. And I remember looking with this glare of hate. The Angel of Death came to find me, man, and we were there, and we fought the entire time. They weren’t taking me.” (That last sentence Paul said with equal parts contempt and disgust.)

The day Paul was released from the hospital is still very much front of mind for him. “When I was being wheeled down in the chair at the hospital, I figured something was up,” he says. “One of the techs that truly helped me the entire time—Liz Vazquez—had a heart that was indomitable. She helped me every day to get up, when I didn’t want to get up; to stand, when I didn’t want to stand; to walk, when I couldn’t find the strength. She said, ‘I’m going to wheel you out of here,'” he says. But instead, the day of his release came, and one of his nurses started wheeling him out of his room instead. He knew something was up right then and there, because he and Vazquez had made a deal that she was going to wheel him out on the big day. The nurse looked at Paul and said, “Liz is downstairs; she wanted to watch you walk.” So, Paul was wheeled downstairs, and he noticed that the medical staff had communicators on, “kinda like Star Trek,” he jokes. “And the nurse’s goes off, and they say, ‘Let us know when you get off the first floor elevator.’ And I said, ‘What’s going on here?’ And the nurse goes, ‘We need a win.'” He then explained to Paul that the condition he’d been in and the level of care he’d gotten and where he was now—just about to take his first steps of freedom in weeks—motivated the entire hospital staff “to do what we do every day. And we need this just as much as you do.”

“I’ll never forget that,” says Paul.

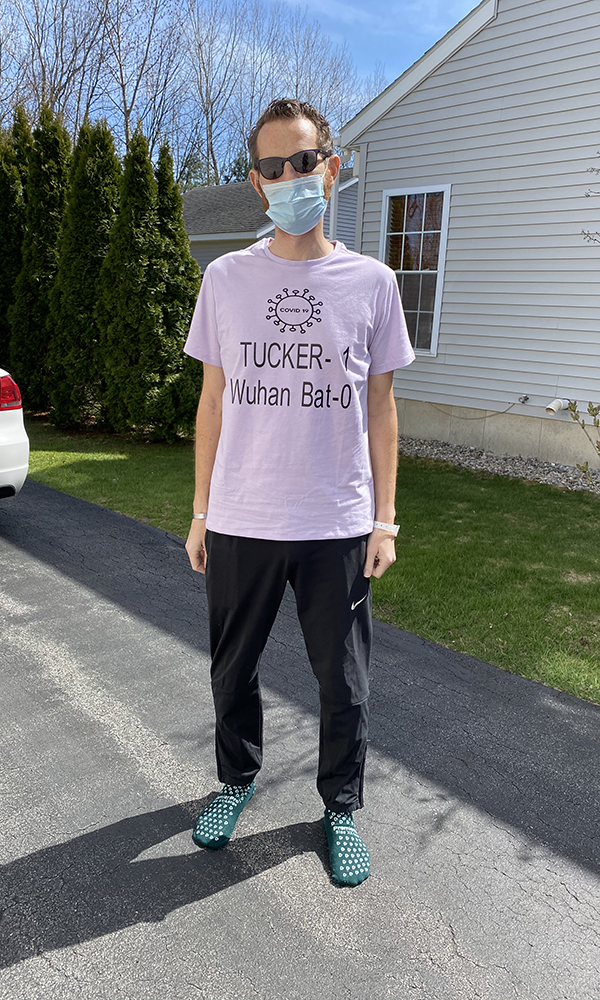

At 2:13pm on Thursday, April 23—and I know the exact time because I was watching the joyous moment unfold, via live stream, on Sara’s Facebook page—Paul emerged from Saratoga Hospital, victorious, wearing a shirt that read: “Tucker 1, Wuhan Bat 0,” referring to his call sign (“Tucker,” which is a long, hilarious story that I promised not to print) and the supposed origin of the COVID-19 virus (a bat in Wuhan, China). The nurse that had been wheeling him stopped right before the entrance and said, “Do you want to do it?” Without thinking, Paul threw off the blanket that he’d been wrapped in, stood up and walked out the emergency room doors, and who was there waiting outside, along with his wife, family and hundreds of well-wishers? Liz Vazquez. “Liz was the one right at the door,” says Paul. “She was the one that gave me the American flag. And I told her, ‘I wish I could give you a hug right now,’ because obviously I couldn’t.” Almost immediately, Paul was overcome with emotion. Vazquez started crying, too, and a big cheer rose up from the gathered crowd. “Those next steps were easy because of the support that I had the entire time and I never knew—that I took for granted before,” says Paul. “I think, maybe, we all take for granted the network of people, strangers even, that we have. G-d forbid you wind up in the hospital tonight, those strangers will take care of you.” When he saw the medical staff with tears in their eyes, he was compelled to give a little impromptu speech. “It was a true ‘thank you,'” he says. “I couldn’t have done it without them; they were my only link to life for a long time.”

Then Paul says something that truly shocks me. “I don’t feel bad that I caught this,” he says. “I’m glad I got it rather than Sara or anyone else, because I was able to do this. I’m able to fight.” (Paul noted early on in the interview that neither Sara nor any of his coworkers at Delta had shown the symptoms of COVID-19.) “I don’t know if I’d have the emotional strength that Sara has; her fortitude through this has been unbelievable. She’s been unbelievable.”

When Paul and I connected, through Sara, of course, for our interview on April 25, it had been almost exactly 48 hours since Paul had taken his first steps out of Saratoga Hospital to a crowd of jubilant and emotional family and friends, Saratoga Hospitals staffers, first responders, members of the military and onlookers. The first thing Paul did when he walked in his front door? Went off and took a long, hot shower. (He hadn’t had the luxury in 28 days, because the medical staff had been worried that the steam from the shower, mixed with the viral breath he was breathing, could’ve gotten into the air and infected others.) His first meal? Filet mignon prepared by Sara, which he was able to cut and feed to himself (again, something that he hadn’t had the ability to do just days previously). Unbelievably, he was also able to return home without an oxygen tank—something he’s been told is a rarity among recovering COVID-19 patients. And unfortunately, he and wife have to stay socially distanced even within their own home, with masks on; and they can’t even use the same bathroom or sleep in the same bed. “I don’t have a timeline, I’m still in therapy for at least another month, I’m still walking those stairs and learning how to stand up and sit down again—I have to take my pulse and monitor my oxygen levels,” he says. But he’s getting better every day, thanks to virtual visits from his care team and in-person appointments with his physical therapists.

Paul’s still amazed by everything that went in to getting him to wake up in the ICU on the 13th and walk out of the hospital on the 23rd. “I joke with Sara that ‘you unplugged me,'” he says, referring to the ventilator. Sara actually has a record of the settings that the ventilator was on, and throughout the nearly 11 days Paul was on it, he says, “the amount of pressure and oxygen that was required says I shouldn’t be here right now.” (Off screen, Sara almost whispers, “It was maxed.”) Near the end of our interview, Paul’s mind shifts to his current profession—and maybe, unknowingly, makes an eerie analogy between it and his fight against the virus. “When you lose all control of everything, you go back to the process that brought you safely under control in the first place,” he says. “Whether it’s an emergency in an airplane…it’s experience, of course. But that experience drives me to go back to the process that keeps us safe. [To] go back to the process that’s been proven by the engineers, the scientists—all the nerds—and the physicists, that this will just still fly like this.”

“You’ve never had any situations like that in the air, have you?” I ask him.

“Not with Delta,” says Paul. “I’ve had a lot with the military: I’ve lost engines, [had ones] that have caught on fire. But again, you rely on your training, you rely on your crew, you rely on that process. And it’s tough, because we’re not necessarily ‘process’ individuals. As Americans, we’re goal-oriented, man. ‘We’re going to do this, goddammit.’ Sometimes it’s hard to slow down and find that process. But sometimes that process will get you through the tough times. I think, sometimes, it’s the only way to get through the tough times.”