The first time I visited Saratoga was in 2015 when I landed a scholarship to the Summer Writers Institute at Skidmore College. The very first thing I did in town? What any respectable writer would: I visited the public gardens at Saratoga’s famed artists’ retreat, Yaddo. I’ll never forget standing next to one of the estate’s fountains, staring at the Victorian-inspired Trask Mansion and thinking: “That’s like something out of Harry Potter…or maybe even Scooby-Doo.”

The mansion, which sits at the center of Yaddo’s 400-acre wooded estate, is looking a lot different these days than when I first saw it. It’s been given a $10 million face-lift, reopening just this past June, along with some other nips and tucks to Yaddo’s grounds. For a place that’s offered residencies to authors, composers, artists and many other creatives since 1926—76 of whom have won a Pulitzer Prize; 68, a National Book Award; and 1, a Nobel Prize for Literature—the money spent was certainly worthwhile. One thing that hasn’t changed since my visit? Its president is still writer and former Elle magazine Editor in Chief Elaina Richardson, who’s been helming the colony for nearly two decades. I sat down with the charismatic Richardson to talk everything Yaddo. It was a good day.

You shocked the publishing world when you stepped down as editor in chief of Elle in 2000 to become Yaddo’s president. What was so alluring about the position?

I’d started to feel what I think many journalists feel who begin as writers— [that I was] being promoted and, in a way, succeeding in journalism, but getting farther and farther away from the things I cared about. The job at Elle was exciting and it was a certain kind of glamour, but I realized that I didn’t hands-on edit stories anymore. I didn’t assign stories; I didn’t write very much myself. One of the things that appealed to me about the Yaddo position was that I thought I’d get closer to the original moment of the work again. I’d be back with people when they’re in the idea stage, the failing stage, the I-have-no-idea-what-I’m-doing stage, which is the stage I actually like a lot. [Laughs]

Tell me some of the most memorable artists you’ve had a chance to host during your tenure at Yaddo.

Gosh, so many. We had Jayne Anne Phillips work on Lark & Termite, Jennifer Egan on Manhattan Beach and all kinds of filmmakers—everybody from Dee Rees (Mudbound) to Noah Baumbach (The Squid And The Whale). Also, big authors such as Jonathan Franzen and Jeffrey Eugenides.

Who do you think are the most important artists to have ever stayed at Yaddo?

I think it’d depend on your taste and your lens. You could probably take a million different approaches. If I were writing a book about Yaddo, I’d focus on just the summer of ’68, when there was a lot of cultural tension and chaos. You had artist Philip Guston and novelist Philip Roth in residence then, and they were working together on a project, basically cartooning the Vietnam War. It was never published, but Guston did the drawings and Roth did the text. So you could take that approach. It’s hard to imagine a more interesting conversation. I also think of Langston Hughes going into Saratoga to have a beer. I wonder what that was like, getting to sit on a barstool next to Hughes.

Historically, Yaddo’s been a pretty mysterious place—especially to Saratogians. Has that been intentional?

It’s conscious in the sense that Yaddo and the whole idea of “retreat” led to the development of some core habits and roles. So, for example, we have quiet hours between 9am and 4pm and after 10pm, which means nobody can come visit your studio. No fellow artists will knock upon your door, and the staff won’t do anything either within quiet hours. We have to protect the idea of “retreat” and peace and quiet and uninterrupted thought time.

But over the decades, what’s also become apparent is that, of course, there’s curiosity. People want to know what happens in these buildings. So we’ve realized the obvious truth that the better a neighbor we are and the more welcoming the public areas are, the more understood “retreat” is, and that you help both by paying equal attention to them. The gardens get more than 50,000 visitors a year. That’s the next stage for this big campaign we’ve been in: to do work on the access roads, the parking area and the gardens themselves. So we’re trying to keep in balance the necessity of “retreat” and that of public access, while also demystifying, in a sense, what happens here at Yaddo.

What’s motivated that decision to start opening up Yaddo to the community more?

To have invested $10 million in the facility, it felt important to me that we were doing that not just for the 300 artists a year who are residents here, but also for the wider community as well, and especially Saratoga Springs and the Capital Region, which were very generous during the renovation campaign. We realized that because we’ve restored the mansion, we have this incredible resource where we can do more year-round events and robust programming, such as concerts in the music room or a movie night on the lawn. And when we fix the access road and public area, it opens up all of these really exciting ideas about how these public areas can be used, perhaps even for mini-festivals.

Also, when I first took the job, I remember feeling strongly that Yaddo was too well-kept a secret. It has a national reputation and a lot of status within a small world, but it really felt to me, especially as times became more charged politically and culturally, that Yaddo had to fill a bigger role in the cultural landscape. We have the history of having been around for 100 years, and we have the power of attracting the world’s greatest artists.

You’re closing in on two decades at Yaddo. Would you say that these renovations have been your biggest accomplishment so far?

Oh gosh, yes. I think, undoubtedly, this moment. We have five new live-work studios—the first new livable spaces ever built on Yaddo’s grounds—as well as a completely restored mansion. Before, the mansion was magnificent but under threat of falling into disrepair. So what makes me feel really proud is this feeling of having set Yaddo up both in terms of outreach and who comes here, as well as the stability of the infrastructure for at least the next 100 years. So we did it!

All these years after leaving Elle, did you ever get back to that original work?

I’m writing again, yes—nonfiction in my case. I went back to doing a lot of reviewing, but I’m working on a big mess of a project, which is about resilience. It’s about why we keep fighting when we’ve lost—a kind of investigation of lost causes.

And when do you think that’ll publish?

[Laughs] I can tell you it’s five years late. Does that help?

Yaddo’s All-Stars

Here are five of the biggest names to spend time at Saratoga’s famed artists’ colony.

It’s fair to say that many artists dream of being able to do a Yaddo residency. Housing everybody from Pulitzer Prize winners to Nobel laureates, Saratoga’s resident artists’ colony is one of the—if not the—most prestigious in the country. But who are the biggest of the big deals to have ever spent time there? saratoga living reveals our top five on this fascinating list.

Aaron Copland One of America’s greatest composers, Copland garnered a Pulitzer Prize in 1945 for his masterwork Appalachian Spring. Fifteen years beforehand, he was working on one of his groundbreaking early works, Piano Variations, during a residency at Yaddo. During that visit, and on a subsequent one in 1932, Copland organized Yaddo’s Festival Of Contemporary American Music, a series which ran into the 1950s, too.

Langston Hughes The quintessential poetic voice of the Jazz Age, Hughes broke down social and literary barriers with his lyrical poetry that embodied the African-American experience. During his stay at Yaddo in 1942, Hughes took part in some early civil disobedience in Saratoga, when he visited the New Worden, a popular bar and restaurant which, at the time, was still segregated.

Leonard Bernstein The first time Bernstein applied to Yaddo, he didn’t make the cut (and he even included Copland as a reference). But Bernstein got the call in 1952. While there, he worked on Trouble In Tahiti, the one-act opera that laid the groundwork for his next two much, much bigger musical scores, Candide (1956) and West Side Story (1957).

Sylvia Plath Revered as one of America’s most brilliant confessional poets and writers, Plath stayed at Yaddo with her husband, poet Ted Hughes, in 1959. On Yaddo’s grounds, the Boston-born Plath participated in an author’s reading and finished poems for The Colossus, the only collection of poetry that she ever published in her lifetime.

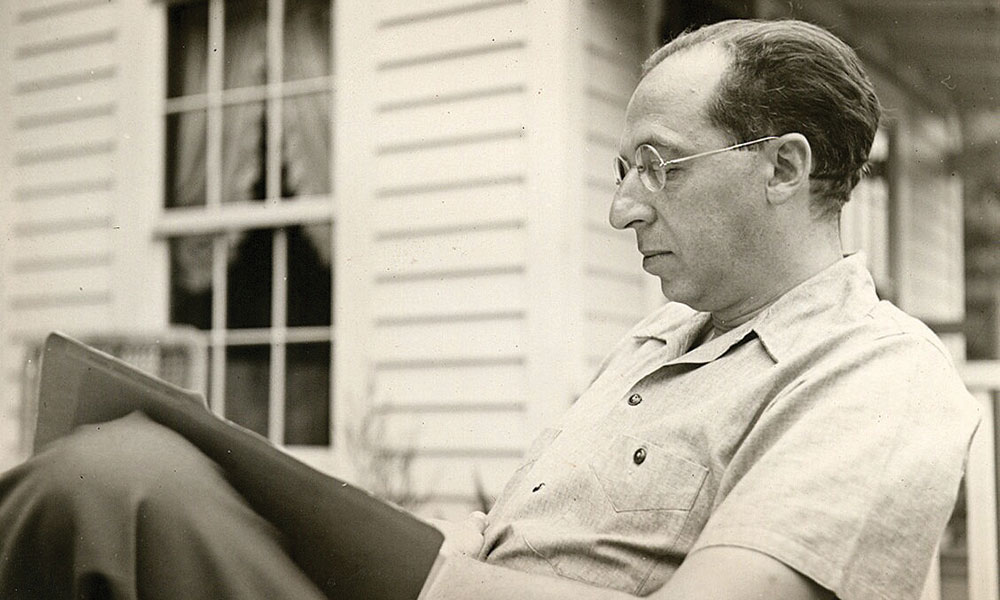

Saul Bellow The only Yaddo resident to have been awarded a Nobel Prize, Bellow was a regular colonist throughout the 1950s (along with his good friend, American novelist John Cheever). During a stay in 1959, Bellow worked on portions of Henderson The Rain King, one of the Canadian-American writer’s most enduring works.