It’s not everyday that you graduate from college. Nor is it everyday that you graduate at the age of 31—1,100 miles from where you were born and raised. This past Saturday, May 19, was Skidmore College’s 107th graduation commencement ceremony. Attended by approximately 5,000 people, yours truly was there but not as a spectator or a member of the press (as you might think), but rather a participant. With 672 others dressed in cap and gown, I walked across the stage to shake the hand of Skidmore President Philip Glotzbach and receive my diploma. The truth is, I never thought I’d be here, in this beautiful, unique city, graduating from this tiny but prestigious liberal arts college.

Honestly, I thought the whole thing would be a snooze-fest (nothing specific to Skidmore—most graduations are so formulaic and sententious that they’re almost designed to be snored through). And while there were still plenty of platitudes to go around, I was genuinely struck by the stories and diversity of my graduating class. Skidmore sometimes has the reputation of being a school only for affluent, white students from the East Coast; yet the class of 2018 had graduates from almost 30 different countries, 87 of which were first-generation college students. Even more impressive, however, were the words of the two main speakers at the commencement.

Many will remember that last year’s commencement address was given by none other than American TV icon Oprah Winfrey. A tough act to follow, I realize. Though perhaps not quite as well known, this year’s speaker, Alison Bechdel—an American cartoonist, whose critically acclaimed graphic novel, Fun Home, was turned into a Tony Award-winning Broadway musical—gave a speech that, in my opinion, was more impactful and personal than her predecessor’s (Fun Home played at Proctors last fall). Aside from her bestselling graphic novel, Bechdel’s also known for her cartoon strip, Dykes to Watch Out For, which gave the world the now-famous Bechdel Test, a set of criteria that asks whether a work of art (fiction or film, for example) features at least two women in a scene together who talk about something other than a man (the test is an indicator of gender inequality and misrepresentation in the arts, and you’d be surprised how much art fails it). Awarded an honorary doctorate of letters at the ceremony, Bechdel spoke about her own experiences post-graduation and how, instead of going to graduate school and following the straight and narrow, she started a comic strip for a magazine that later became Dykes to Watch Out For. Though she wasn’t paid anything to start this comic, it became the very thing that launched her career. “I don’t often like to give advice, because I rarely follow it,” said Bechdel. Still, she told my graduating class one simple thing: follow your passion. “Because the job of creating positive change in the world is such hard work, it will go a lot better if you really enjoy what you’re doing.”

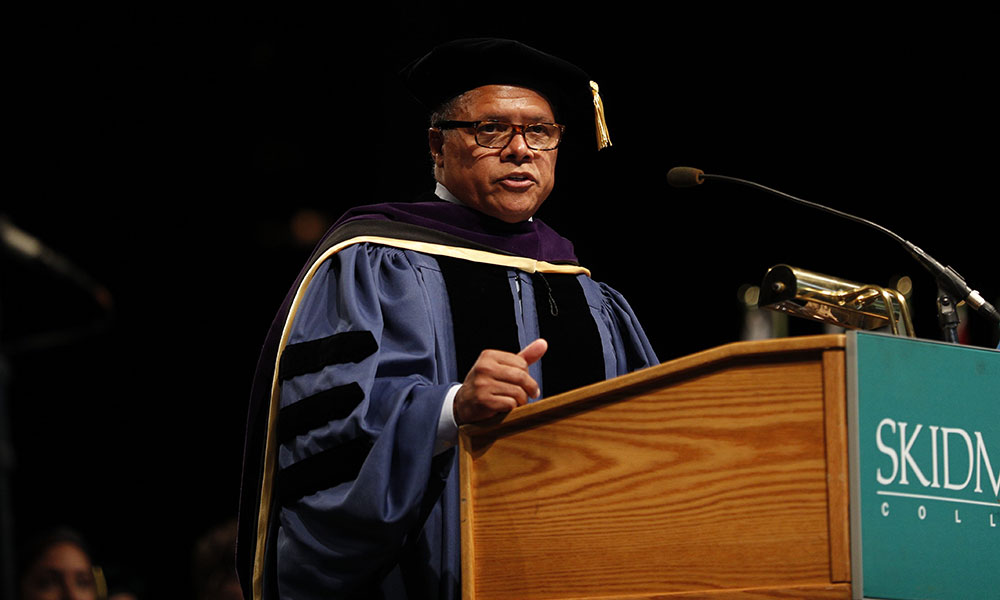

While Bechdel gave a short, funny and effective speech, the portion of the ceremony that moved me the most was a short anecdote told by Dr. Robert S.D. Higgins, who was awarded an honorary doctorate of laws. An Albany native, Dr. Higgins is Johns Hopkins Hospital’s surgeon-in-chief as well as a world-renowned authority in the field of coronary bypass surgery and heart and lung transplantation. Toward the end of Dr. Higgins’ speech, he described the moment when a new heart is placed inside a patient. “When you remove that heart from its Igloo cooler, it’s nothing but a lifeless muscle,” he said. “But when you put it in place…it begins to beat instantaneously.” Dr. Higgins then imitated the sound of a heart beating anew. “It gives me chills every time.”

I don’t know why Dr. Higgins’ speech hit me so hard. I graduated an English major and certainly have no plans of going on to medical school (I can’t even stand to write about surgery). But Higgins wasn’t addressing just the students in the sciences. He was talking to all of us, about the indomitability of not just the human heart but the human spirit as well. That we can do anything—even finish our undergraduate degree at 31.