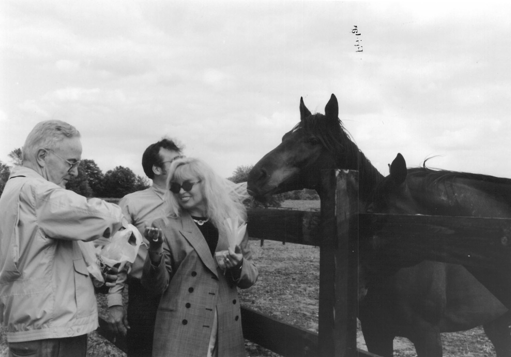

Photo by Patty Wolfe

Meaningful change comes to fruition only after a person chooses to care. For the Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation (TRF)—the oldest and largest organization of its kind—four decades of systematic change in the way that Thoroughbred aftercare is approached can all be traced back to one woman’s deliberate choice to care about the fates of other beings.

More than 40 years ago, a young advertising executive from New Jersey had an experience that we are all familiar with: She picked up a magazine and read an exposé that roused her empathy and indignation. The scoop? Trainer Daphne Collins was vocalizing the neglect and abuse that Thoroughbreds often face when they are no longer able to race.

Most people have felt enraged in a similar way at one point or another in their lives after discovering great injustices. Monique Koehler, however, was not “most people.” Though it would have been easy to resign to a sense of helplessness and defeat in the face of such a large issue, she did not. Instead, she chose to care deeply—and take actions to match. She resolved to give the horses a better fate.

Since Koehler founded the Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation in 1983, the Saratoga-based national nonprofit organization has never wavered from its mission: “To save Thoroughbred horses no longer able to compete on the racetrack from possible neglect, abuse, and slaughter.”

If the word “slaughter”in a nonprofit’s mission statement makes some uncomfortable, then TRF’s plan is working. When the pioneering organization was founded, horse racing was in its heyday. While today there is a whole industry of organizations dedicated to maintaining the wellbeing of Thoroughbreds in retirement, this has not always been the case. For Koehler, getting the public to care about the fates of the horses also meant not being afraid to talk about uncomfortable realities. Her boldness shapes the organization to this day.

“We have to say that,” says Kim Weir, TRF’s director of major gifts & planned giving, of the organization’s blunt mission statement. “That’s why we’re here.”

When Weir says “we,” she is talking about the foundation, but she could just as well be talking about its staff—a small but mighty collective of folks whose lifelong passions for horses and horse racing have instilled in them a reverence and responsibility to their equine friends. Fittingly, there’s a saying that peppers conversations with the TRF staff like a musical refrain: “Come for the horses, stay for the people.”

While TRF’s genesis was in the mind of one firebrand woman, the organization has always been inextricably part of a wide web of generous and helpful people. “It’s a whole cast of people who said, ‘yes,’” says Weir as she reflects on the organization’s serendipitous history, something she and her colleagues are doing often these days, as the organization celebrates its 40th anniversary.

Weir knows that being able to tell someone “yes” is a gift—that the word yes possesses a certain magic that unleashes far greater creative possibilities than one person could ever make happen on their own. While there have been thousands of “yes” moments that have helped TRF grow over the past four decades, one of the most seminal came from the New York State Corrections Department.

While Koehler had been exceptionally successful in raising the required funds to start making a difference in the lives of horses, she didn’t have anywhere to house them once they were rescued. Fatefully, the New York State Corrections Department had just acquired an old dairy farm in Wallkill to serve as a land buffer. There were no other plans to utilize the land. Thus, the two unlikely partners joined together, and TRF’s flagship Second Chances program was brought to fruition as a result.

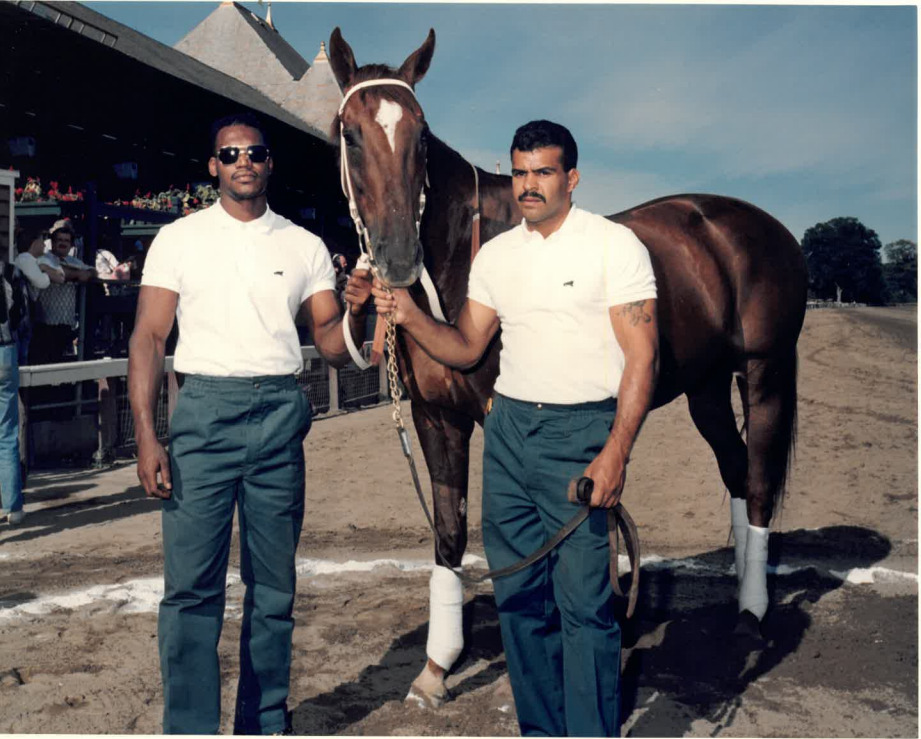

Second Chances—which currently exists in eight states—is an innovative program where inmates participate in vocational training and life skills–building as they provide care to retired racehorses.

“This model of being in the prisons has really been successful,” says Executive Director Kelly Armer. “They’ve found that folks working with the horses don’t return [to prison], because they’ve found purpose.”

Indeed, the men who participate in Second Chances often make the same profound discovery as Koehler, Weir and Armer all have during their time with TRF: What starts as a sense of service and responsibility to the horses eventually turns into a lesson in humanity and connection.

Armer recalls a moment that has stayed with her since a recent trip to Wallkill: “A big man came up to me and goes, ‘I have to tell you, I was afraid of these horses. I’m a big guy, and I was afraid of them.’ The biggest thing for him was that he overcame his fear.”

On the other side of his fear was a sense of pride and purpose that he had been missing for so long. Armer and Weir bestow all credit to the horses.

“While the [ex-inmates] may be scared, the horse is looking at them with zero judgment,” says Weir. “That’s when it sort of cracks the door open because the horse doesn’t know where they came from and doesn’t care what they did five years ago or five minutes ago.”

Horses place their trust in their caretakers no matter their personal history. When given the chance, people will rise to become the version of themselves that the horses see.

“We’re finding,” Armer says, “that we can’t keep up with the correctional facilities that want to open a site.”

It’s a problem that she and the rest of the TRF staff are happy to have. Currently, the organization is establishing a site in Washington; Maryland is next on the horizon.

When asked what the next 40 years look like for TRF, Armer’s answer is growth, growth, growth. They’ll keep doing as they’ve done, which is tapping into the magic of a yes and the grit of those who choose to care.