In dance, as in life, we fall in love all of a sudden and then, if we’re lucky, we can spend a lifetime working out the details. Ballet, much like deep, enduring love, is nourished by memory at least as much as by its living and breathing everyday celebration. The first time we see Giselle, The Nutcracker or Esplanade is the occasion of the creation of timeless memories that, for each of us, inform the depth and meaning of subsequent experiences of these ballets. I should confess here that my own memories of Giselle—which the Ballet Nacional de Cuba is performing at the Saratoga Performing Arts Center (SPAC) June 6-8 in the most complete staging to be seen anywhere—go back a bit. To me, it’s personal.

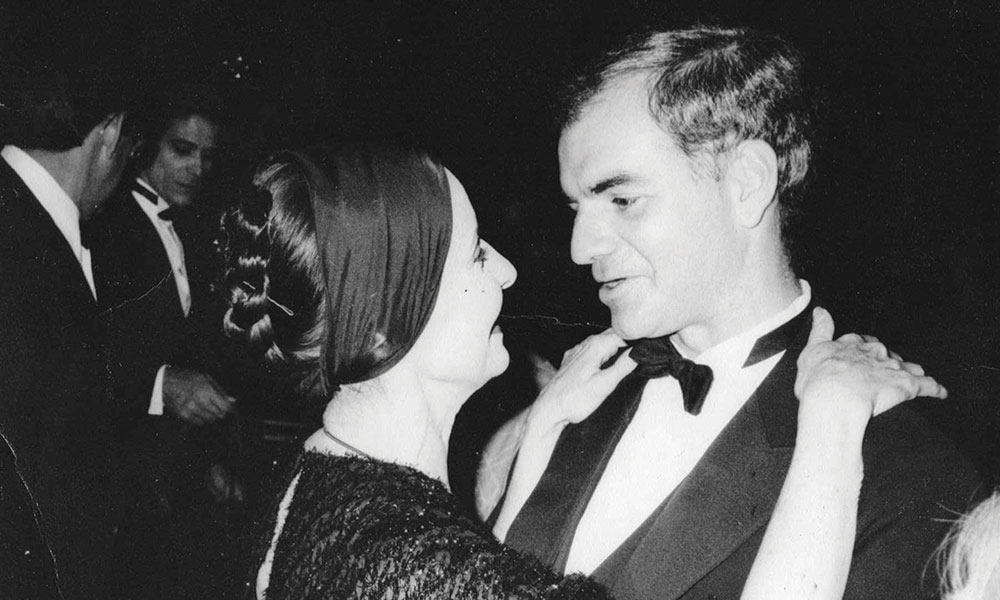

I was born in Havana, where my mother was a dancer with Ballet de Pro-Arte Musical, the precursor of today’s Ballet Nacional de Cuba. Giselle, with Alicia Alonso and Igor Youskevitch, was the first ballet I ever saw, when I was six years old. Far from home and a bit of a lifetime later, I first interviewed Alonso for The Washington Post while I was still a philosophy graduate student at Georgetown University in 1980, and I’ve followed the Cuban ballet adventure critically, passionately ever since. A few years ago, I aimed to bring together memories, history and criticism in my book Cuban Ballet. In the meantime, as always, memory brought its own surprises. I’m fortunate that my own dance memories are many, and I also know that, at its most sublime, ballet can say things that cannot be said any other way.

Ballet certainly is a universal language. With Giselle in particular, that language for me has a strong Cuban accent. I’m not alone, mind you. There’s something about Alonso’s Cuban dancers. “When you see a Cuban dancer,” says Mikhail Baryshnikov, “he moves like nobody else, but in such a simple, noble manner.” The version Alonso first danced in New York City in 1943 and in Havana two years later—and the version I saw as a child in the 1950s—became something else: Alonso expanded and choreographed it anew for her Ballet Nacional de Cuba and for the Paris Opera Ballet in 1972, then for the Vienna State Opera and other major theaters. Giselle became the calling card for the historic US debut of the Ballet Nacional de Cuba at The Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, in 1978—a run that I will simply never forget. That Alonso staging note-complete, idiomatic and frankly, gorgeous—is what’s coming to Saratoga. It’s a revelation, a sacrament of beauty each time the curtain rises.

Giselle has stood the test of time and mirrors the best in all of us in ways that transcend the centuries. It’s about love and loss, about forgiveness, about hope. It’s a masterpiece that speaks to us today at least as frankly and surely and sweetly as it did to its first audiences in 1841. Alicia Alonso’s Ballet Nacional de Cuba boasts an extensive repertoire, but it’s this romantic ballet in particular that the Cuban dancers claim as their own. Alonso’s Giselle is one of the most thrilling living, cultural spectacles of our time.

Giselle had its world premiere at the Paris Opera on June 28, 1841, with Carlotta Grisi in the title role, Lucien Petipa as Albrecht and Jean Coralli as Hilarion. It didn’t take long for the ballet to reach Havana, where it premiered at the Teatro Tacón on February 14, 1849, with Henrietta Javelly-Wells as Cuba’s first Giselle. The ballet entered the repertoire of the Teatro Nacional, now the Sala García Lorca of the Gran Teatro de La Habana, on February 8, 1917, with Anna Pavlova and Alexandre Volinine as Giselle and Albrecht. In 1920, three years after Pavlova’s first Havana Giselle, Alicia Alonso was born. That a French masterpiece based on a German poem, once best known through Russian interpretations, would be spectacularly recreated and defined by a Cuban ballerina is one of history’s loveliest surprises.

The first decades of the 20th century saw interpretations of Giselle, including Pavlova’s and even Olga Spessivtseva’s, which began filtering the ballet’s romantic vision through a Janus vantage point of both classical and modern eyes. It was the tragic Spessivtseva’s interpretation with the Ballets Russes that the young Antony Tudor learned and later taught to Alonso in the early days of Ballet Theatre. From the start, Alonso was miraculously at home with the romantic impulse, and she would in time transform many of the work’s details for contemporary audiences. She did this against terrifying odds. Many artists, of course, have been driven by cruel limitations, but Alonso’s case is unique. In a field that depends so much on the mirror and dancer’s self-image, and in which the visual presentation of the dancer’s own body is at the heart of artistic creation, here was a woman who was told at the outset of her career that she would soon be blind and would never dance again.

Alicia Alonso first suffered a detached retina in 1943, before her glorious prime. As she lay blindfolded recovering in Havana from the third of a lifelong series of eye surgeries—with her head couched between sandbags to prevent her retinas from detaching again—she ran through the whole of Giselle in her imagination, moving her fingers in her lap to rehearse steps as well as feelings in the dark. “I kept dancing in my mind,” Alonso recalls. She resolved to make real what her imagination dictated, to refuse to accept the limiting conditions of her existence. In doing so, she imagined what would become today’s Giselle staging—not only for the title role, but with the whole ballet living up to its choreographic potential. As the great French dancer, choreographer and opera director Maurice Béjart put it, “Alicia was born so Giselle would live.”

Philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre is right in his assertion that freedom is what you do with what has been done to you—that consciousness and choice are one and the same thing. Alonso was and is free, material conditions be damned, and blind or not, she became one of the greatest forces in the history of ballet. In 2018, her age is nearing the century mark, and when she says, “I plan to live to be 200,” one is tempted to believe her.

The story of Giselle is simple: A peasant girl falls for a boy who’s really a nobleman in disguise; when his elegant fiancée turns up, Albrecht abandons Giselle with the ease of a cad who’s already had his way with her. Giselle descends into madness and dies. We know she was sickly anyway, but she may’ve killed herself or perhaps just died of a broken heart. Whatever the reason—and each ballerina has the freedom to choose one within the choreography—Giselle’s love for Albrecht transcends the grave. In Act II, when vengeful female spirits roam the night to punish men who betrayed their lovers, there are miracles afoot, and Giselle’s ghost dances with Albrecht until he is safely back in the sunshine of a new day. By then, of course, Albrecht has lost her forever.

The choreography, too, is in many ways simple. Giselle was created in 1841, when seeing women up on their toes was still a novelty and the illusion of dancers “floating” was a recent bit of stage magic. There were later additions to Jules Perrot and Jean Coralli’s original choreography by Marius Petipa, but except for the Russian bravura of Giselle and Albrecht’s solos, these were kept to a minimum. The ballet we have now is very much a product of Paris in the Romantic Era, not least in terms of choreography. Nothing in Giselle is merely decorative: Every step and gesture has a theatrical purpose. “She can be a simple peasant, but she must be possessed of an elevated spirituality,” says Alonso. “My goal always has been to bring together the surreal and evanescent nature of the spirits that come alive onstage with the very real, earthly reality of human love.”

Details matter as well. Dramatic atmosphere is everything. If the arabesque in all its forms makes up most of the choreography, it’s a revelation to witness how much feeling that one step can communicate. Many details in the Cuban version are modern and designed for today’s audience. In the pantomime, for instance, Giselle tells Bathilde she sews for a living. In the original 1841 libretto, she mimed the action of weaving, which would be meaningless to a modern audience. This is a moment among many, a change in dramatic detail that Alonso devised while working with Tudor for what was to be her unexpected debut in the role in New York in 1943. Audiences know what sewing looks like, but few can envision weaving. It’s at once endearing and revelatory to find in the 21st century some smaller European companies such as Moscow’s Stanislavsky Ballet or St. Petersburg’s Maly Theatre Ballet maintaining in their repertory the “weaving” mime in Act I that virtually every other company by now has changed after Alonso’s example, from Havana to Paris, from San Francisco to New York and London. Nearly all other ballet companies have followed the Alonso staging in this and other details. “Real tradition; living, valid tradition must be open,” says Alonso. “It must be received from all around. One has to search out tradition, study it, acquire it and then feel free to live it.”

Some changes in Giselle are accidental. The round dance for the villagers in Act I originally consisted of one long line, half facing one way, half the other. Alonso, with her severely damaged eyesight, could not negotiate the uninterrupted run from Giselle’s end of the line to Albrecht’s—and this with the help of subtle finger-snapping or whispering from the helpful corps. So, in the Alonso version, the line is broken into four spokes of a wheel, all facing forward, with an easier route for this blind Giselle to follow in the dark. The change has worked so well on purely aesthetic and practical terms (a four-spoke wheel of dancers takes up a smaller stage area than one large line spanning a wider circle) that several productions from New York to London now also dance it this way—even without a blind ballerina. The resulting impact on the performance practice of Giselle is remarkable. It cannot be overstated how difficult it is to dance without sight—just trying to walk and turn with one’s eyes closed should suffice to demonstrate this. Paradoxically, to accept one’s lot is also to refuse. When Alicia Alonso had her dancer’s praxis stolen by blindness, she both accepted that brutal physical condition and refused to be determined by it. And the rest is history.

Most of Alonso’s changes to the original 1843 version of Giselle are, of course, not accidental, but rather conscious aesthetic choices. Turning the interpolated Act I peasant pas de deux into a dance for ten villagers manages to preserve a beloved scene in the Giselle tradition going back to the original Paris production, while at the same time avoiding the dramatic awkwardness of introducing an extra principal couple without a story of their own. In short, it’s a lovely way to introduce young stars. This scene, as traditionally danced, never fails to stop the dramatic action; Alonso’s solution solves that problem. Earlier in Act I, when the entire corps of villagers turns and stares over their shoulders at Hilarion, who’s unmistakably identified as being outside of the community identity embodied in the ensemble, the clarity of dramatic detail also subtly appropriates and elevates what’s elsewhere a dispensable connective musical passage. These and other musical matters, incidentally, could by no means be taken for granted before Alonso restored the Giselle score to its full splendor in 1972, when her productions both for the Paris Opera and the Ballet Nacional de Cuba boasted the first note-complete versions of Adolphe Adam’s score since the original 1843 version.

Alonso’s Giselle, over all those years and above all her other achievements, has been a profession of faith. Capturing an era and transcending it in triumph have made Giselle rank among the top theatrical works in history, including Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Corneille’s Le Cid, Wagner’s Parsifal and Ibsen’s Peer Gynt. Ballet has no richer masterpiece than this miraculously simple, endlessly fascinating dance about a love that overpowers death. Hegel famously observed that the owl of Minerva takes wing at dusk: Wisdom and deepest understanding arrive at the close of an epoch, at the birth of a new day. That’s true of Giselle, at once the apotheosis of romantic ballet and the glittering model for all classical ballets to come. It’s true also of Alonso’s staging.

Alicia Alonso truly was born so that Giselle would live. Her unique Giselle for the Ballet Nacional de Cuba remains a dialectical synthesis of boundless romantic passion and elegant classical rigor, of impeccably schooled respect for our cultural past and indomitable faith in our future. In the truest existential sense, she is what she does, and what she does above all else is this. Alicia Alonso is Giselle, in history, living onstage, forever in my memory.