Earle I. Mack is a businessman with a deep philanthropic nature. A veteran of the U.S. Army and a lifelong horseman, Mack is now focused on how retired Thoroughbreds can help military veterans heal.

Mack found that there was great anecdotal information about how horses can help veterans, but nobody knew how or why it worked. A former chairman of the New York State Racing Commission, Mack approached some of the finest minds at Columbia University with specific questions: How does equine-assisted therapy help Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and how do we create a uniform program that can thrive across the country?

Mack’s vision and drive to help not only veterans but also retired racehorses — and his $1.2 million in funding — led to the research necessary for The Man O’ War Project.

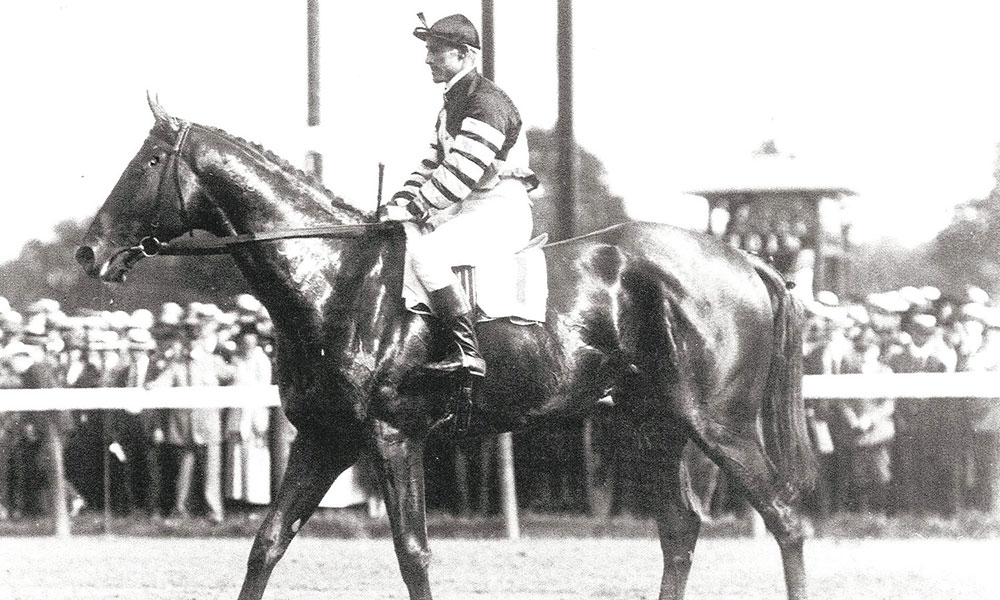

A former ambassador to Finland, Mack named the program for Man O’ War, the champion racehorse known for his mind-blowing speed and still controversial defeat at Saratoga nearly 100 years ago.

“This is the first and only university-led professional research project to test the use of equine therapy to treat veterans with PTSD. It was developed by the impressive Columbia team lead by Dr. David Shaffer,” Mack says.

Two Columbia researchers — Dr. Prudence Fisher, professor of clinical psychiatric social work, and Dr. Yuval Neria, professor of medical psychology and director of the Trauma and PTSD Program — are the co-directors of MOW. They recently attended the Equestricon in Saratoga Springs and spoke at an Aug. 14 seminar. These two researchers, who are not horse people, began this work from the ground up, which lends the study “a great deal of integrity,” says Anne Poulson, president of MOW.

Drs. Fisher and Neria did not have preconceptions about equine therapy, although Neria is a veteran and runs the PTSD program at Columbia. Now at about the halfway mark of their research, Fisher and Neria are amazed at the results.

Approximately 50 percent of all veterans will not seek therapy or any kind of help. Of those who do seek help, nearly half drop out. But so far, there has been only one veteran who did not complete the MOW program at Bergen Equestrian Center in Leonia, N.J., and this was because the veteran lived too far away. The center is right across the George Washington Bridge, convenient for many veterans and the researchers, who commute from New York City.

Poulson says the setting is serene: “a beautiful, full-service facility on a great deal of land, so you drive in and all of a sudden you take a deep sigh because it’s so lovely.” For many veterans who shy away from more traditional therapy, this sort of environment is key, she says. “Once they get in this therapy, they stay, they want to stay; they actually want the program to be longer than eight weeks.”

Everyone involved with MOW is hopeful. Last year, they created the 100-page manual and the eight-week program with 60 veterans, and this year, the results are not only consistent with those of the pilot group, but even better. The long-term plan is to take the program to different locations in the country, perhaps to programs that already exist but would like to become standardized.

MOW is not aiming to replace programs like Saratoga WarHorse, but to track results and create uniformity. “We really believe that all these programs do great work, and ours is putting the science behind the feel-good part of it,” Poulson says.

One frustration is not being able to help veterans who don’t live close to the Bergen Equestrian Center. MOW has a website with a contact page for veterans, but if these men and women are in California or Texas, they can’t participate.

“There are clearly people on a daily basis who want to see if it’s the kind of alternative therapy that works for them, where other therapies failed,” says Poulson. And these veterans are in “pockets all over the country.”

In 2017, the program has stepped up, which helps funding. About 25 percent of what’s needed has been raised, and more is expected, so there is optimism on the small but energetic board. “Our hope is when the study is completed,” Poulson says, “and we have our published results to go to the VA (Department of Veterans Affairs), the DOD (Department of Defense) and the NIH (National Institutes of Health), we can show we’ve proven this works in a relatively inexpensive way to save a lot of lives.”

During their eight weeks at MOW, no riding takes place during equine therapy sessions, and the veterans gain confidence and skills beyond learning how to handle a large animal.

“Veterans learn how their actions, intentions, expectations and tone have an impact on their relationship with the horses (and ultimately the people in their lives),” the MOW website states.

Every day in this country, 20 veterans take their own lives. There are not enough programs to help the veterans who return and find themselves unable to assimilate back into their old lives or to find solace from careers, friends or family. When traditional therapy falls short, there’s not enough access to other programs. Because MOW is affiliated with recognized PTSD programs like the one at Columbia, there is a firm comprehension of what many military men and women find themselves struggling with when they return, and recognition that, for some, these struggles last a lifetime.

“It’s not to say this is a panacea,” says Poulson, “but it is working for many, and if it can become nationally distributed, it’s another avenue… That’s what we need to do, create these avenues of alternative therapies because something that works for one person may not work for another.”

The researchers hope to complete their work within six months to a year, she says. “Some of that will depend upon having a steady stream of funding, but we’ve been very encouraged by what we’ve seen… and being here in Saratoga has been wonderful.”

Mack, the founder of MOW, is a “remarkable man,” Poulson says. “The horse industry and the veterans are lucky to have him.”