On a recent trip to Al’s House of Sports Cards in Schenectady, I was making my way through one glorious, disorganized heap of baseball cards after another—setting aside a number of items—when the shop’s owner, Alex Itskov, shot me a mischievous smile and said he knew what I was up to with the day’s delightfully random haul. “You’re trying to buy back your childhood,” he told me. I deadpanned that he should’ve been a psychologist instead of a card shop owner. All jokes aside, I think Alex was onto something that day: Nostalgia’s been a big part of my life as a professional writer; it’s the engine that propels many of my stories forward; sometimes, it’s the central theme. I enjoy writing stories that evoke memories in my readers—that take them back to a moment in time that they remember, fondly, or didn’t know they’d be interested in. That’s why I enjoy writing for saratoga living so much. As a native Saratogian, every story I work on here has the potential for being my (and your) next great nostalgia trip.

So when it came to my attention that a former Major League Baseball player was living in Saratoga Springs and pals with my boss, I was intrigued. One of the subjects I most enjoy thinking, talking and writing about is baseball. I grew up playing it at the East Side Rec, and although my skills on the diamond were mediocre at best, baseball became an unending obsession of mine. My card collection helped fuel that fire, as did my multiple pilgrimages to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in nearby Cooperstown. Not to mention my fierce loyalty to the Boston Red Sox. But above all, what kept me coming back for more was baseball’s incomparable lore; it’s what makes the game so interesting to me. There’s an expansive history of players, positions, strategies, stats, facts, advertisements (i.e. baseball cards) and shenanigans, all of which date back to as early as the 1800s. Baseball is itself a wonderful, whimsical story.

By no means do I consider myself a baseball historian—you won’t find any hardcovers published under my name or a pseudonym at the Northshire Bookstore. But what you will find is that I’ve been quite prolific when it comes to stories about the game (or its cards and memorabilia) online and in magazines. And that I’ve done my homework. I can’t help it: I’m a constantly captivated student of the game, one that’s always trying to sniff out my next big scoop. The latest is about former Major League Baseball pitcher (and saratoga living contributor), Jonah Bayliss. I think you’ll enjoy it. Read on.

Senior Night

Bayliss’ story begins about an hour and a half southeast of Saratoga in the quaint college town of Williamstown, MA. (My parents take annual road trips there for the town’s renowned summer theater festival, which regularly reins in Hollywood actors such as Gwyneth Paltrow and just this year, Matthew Broderick.) Bayliss’ parents ran a moving and storage company in town, and divorced when he was six. One of three boys—he has two older brothers—intriguingly, Bayliss says he didn’t get his athletic ability from either of his parents. (Apparently, it was somewhere on his mother’s side of the gene pool, but he can’t be certain.) Despite his lack of athletic prowess, Bayliss’ father was a music polymath, having been in three separate bands while growing up in Detroit, playing guitar in one, drumming in another and singing in a third. “He didn’t really know a ton about sports, which is why I think it worked,” says Bayliss. The way he describes it, Bayliss and his older brothers would just go up to their father and ask if they could play baseball or hockey, and he just shrugged and said, “Sure.” He wasn’t really interested in molding his children into something concrete or predetermined; he just wanted to let the answers to what his kids were going to grow up to be present themselves. “So what does my dad do?” asks Bayliss, rhetorically. “He builds a batting cage in the backyard. He builds a rink every [winter]. He doesn’t know how to skate or anything about hockey, but he was like, ‘This is what you guys want to do? Here you go.'” His mother was equally as supportive of her boys’ athletic endeavors, traveling to every one of her sons’ games throughout their entire childhood—and well beyond that. “She put 25,000 miles a year on her car,” says Bayliss.

This was all long before Bayliss ever decided baseball was his ticket to glory. Although he did play baseball, back then, the young New Englander was a hockey guy, with Division I college aspirations—but he felt like he was being held back from his dream at the public school level. “I realized that if I was going to pursue hockey in college, I needed to find out if I was any good,” he tells me. So one night, he picked up a copy of Hockey Night in Boston magazine—which compiles news and stats on all the top youth hockey players and programs in New England—and pored over the section ranking the top ten private high school hockey teams in his area. He crossed off the ones he didn’t think he’d have a shot at getting into and applied to the rest. He ended up getting accepted at Lawrence Academy in Groton, MA, and redoing his junior year, all in the name of hockey.

And what do you know? Soon after landing on campus, he made the Lawrence Academy hockey team. But what started out as a personal litmus test to see if he had what it took to play D-I hockey a few years later in college, quickly became a struggle to even get time on the ice. Playing for legendary hockey coach Charlie Corey, Bayliss practiced alongside future Boston College and Dartmouth College team captains—in other words, the cream of the prep-school hockey crop—and soon realized he might be better suited for a D-III program. The straw that broke the camel’s back came on the last home game of Bayliss’ prep school career—senior night. Despite having his parents in the stands and his team absolutely annihilating Concord Academy that night, posting a lopsided score of 8-1, Coach Corey refused to put Bayliss in the game. That night, Bayliss broke up with hockey. He went straight to Coach Corey’s office and quit the team.

Holy Trinity

Luckily, baseball had always been lurking around in the shadows. Bayliss had played in public school and at Lawrence Academy, though the latter team, unlike the hockey program, was subpar. When it came time to apply to college, one of his older brothers, Jarrett, who was himself a talented collegiate pitcher, made mention to his D-III baseball coach at Trinity College—a renowned small liberal arts school in Hartford, CT—that he had a younger brother with a strong pitching arm. And just like that, Bayliss had an in. So he ended up becoming the second Bayliss boy to attend Trinity, and besides making the baseball team, he tells me that he majored in partying (he was “prolific”) and psychology (which would oddly come in handy later on in his baseball career). Sharing a team with his older brother turned out to be a hidden boon: “He’s where I got my work ethic from,” says Bayliss. When he was a freshman and his brother, a junior, the elder Bayliss was attempting to get drafted by a big-league ball club. And in making that final push, Jarrett started a highly regimented training program, which he enlisted his younger brother to take part in. Bayliss saw his brother’s dedication and respected the hell out of it. But in the end, it was all for naught; Jarrett didn’t get drafted, and it crushed him, says Bayliss. (Thankfully, there’s a happy ending to Jarret’s side of the story: He wound up taking over the family business and is still running it to this day.)

Now, armed to the teeth with a take-no-prisoners work ethic and workout plan, it was time for younger brother to shine. In the summer of 2001, right before the start of Bayliss’ junior year of college, he was playing in the New England Collegiate Baseball League—sort of a summertime mixer for amateur college ballplayers who are would-be or wannabe pros—and after one game in which he pitched particularly well (he was hitting the radar gun, consistently, in the 90s all game long), Bayliss was approached by a baseball a scout from the Red Sox, who asked him whether he had ever thought about playing professional baseball. “I looked him right in the eye and said, ‘No,'” says Bayliss. The thought had never crossed his mind. The scout said he might want to reconsider. On Bayliss’ ten-minute drive home to his host family—summer ballers get paired up with local families for the duration of the season—that’s when everything came into focus. The seed had been planted that he at least had a chance to play in the bigs. “I went to the bed that night with the notion that when I woke up in the morning, from that point forward until the end of my college career, I wasn’t going to look in the mirror and say, ‘Damn, I wish I’d done this differently.'” So when he returned to college, he took that foundation for success that his brother had helped lay for him and cranked things up to 11.

The Mental Game

By senior year in college, Bayliss was a lean, mean pitching machine and was pretty much a lock with MLB scouts, who were coming out to watch him throw at Trinity regularly. So it wasn’t all that big a surprise when he got drafted in the seventh round of MLB’s amateur draft that June. Actually, that’s not altogether true; Bayliss thought he was going to be a Cleveland Indian, and his brothers had side bets on where they thought he was going to end up. None of them picked the Kansas City Royals, who ultimately drafted him. And while you might expect that being drafted by a multibillion-dollar professional sports organization might’ve evoked an “I’m set for life!”-type reaction, Bayliss tells me it brought on more of “a lesson in complacency.”

Just 21, Bayliss signed the requisite working papers with the Royals organization and was promptly sent 2,636 miles away to Spokane, WA, to play in the second-lowest level in professional baseball: Class A Short Season. (Somewhat ironically, the Royals’ affiliate was called the Spokane Indians.) It’s the baseball equivalent of freshman orientation; it kicks off shortly after the draft in June and brings together a number of newly drafted players from across the country—both from high school and college—the majority of whom don’t know one another. They’re all über-talented, but the organization has placed them in Class A Short Season, because it believes they’re not ready to play against older, more savvy players who’ve been in the minors for a few years already (read more about the various levels of Minor League Baseball here). “They put you up in a hotel for three nights,” says Bayliss. “The team does its best to pair you up with somebody that has some sort of commonality with you.” So his assignee was the only other New Englander in the bunch, Matt Tupman, a catcher, whom he quickly became close with (they would end up playing together every successive year through AA).

So what about that first taste of pro ball? “It didn’t go great,” says Bayliss. (He ended his tenure with the Indians going 4-8 with a 5.35 ERA, though, it’s worth noting that of the entire pitching staff that played for Spokane in 2002, only Bayliss and future Cy Young Award winner, Zack Greinke, eventually made it to the majors.) Despite his rocky start, he kept working on his mechanics, pitch selection and velocity and slowly made his way up in the ranks. During this series of sojourns, Bayliss saw a lot of guys just as talented as he was flame out. That’s where his chill demeanor (and maybe, that college psych major) came in handy. Bayliss tells me that, in his opinion, the key to success in baseball isn’t really whether you can strike out 20 guys in a game or hit towering homers; it’s all about what goes on between your ears. At least for pitchers, it’s all about resiliency; if you can come back from a particularly lousy outing or series of pitches, you’ll be OK. If not, it’ll get to you, and you may never recover. Luckily, he didn’t have that problem—at least for the majority of his career, and it was a damned good thing: It would be nearly three years before Bayliss made it out of the minors.

By the spring of 2005, there was a glut of starters in the Royals organization—led by young gun Greinke and wily veterans such as José Lima—so Bayliss was given an ultimatum by his minor league coaching staff: He could either stay a starter and be stuck at a lower level in the minors, or get promoted to AA as a reliever. He chose plan B, and by June, he found himself with a major league call-up. His first strikeout victim? Memorably, Chicago White Sox legend (and future Hall of Famer) Frank “The Big Hurt” Thomas. For Bayliss, seeing Thomas at the plate, with that unmistakable stance and those insane numbers, wasn’t anything that sparked any doubt or fear in him; it was just another body—albeit a six-foot-five, 240-pound one—at the plate for him to try to send lumbering back to the dugout. “On a deeper level, you just see it as a win-win,” says Bayliss. “I just got [to the majors], so I’m not supposed to strike this guy out, but if I do, that would be pretty cool. Throughout my career, I always found that I had success with the big-name hitters and got eaten alive by the lesser names.” Guys that had Bayliss’ number included former Cleveland Indians slugger Richie Sexson and one-time St. Louis Cardinals outfielder So Taguchi; he also gave up towering home runs to future Hall of Famer Ken Griffey, Jr., slugger Cliff Floyd (the ball flew out of PNC Park in Pittsburgh into one of the three rivers), the Padres’ Khalil Greene (a grand salami) and New York Yankees star Bernie Williams.

On the other side of that coin, Bayliss’ high-profile K victims read like an MLB All-Star lineup card. Some of the biggest names included the Yankees’ Derek Jeter, Alex Rodriguez, Robinson Canó and Hideki Matsui; and in one appearance against his hometown heroes, the Red Sox, he retired six players in a row (the victims were, in order, Jason Varitek, John Olerud, Bill Mueller, Tony Graffanino, Johnny Damon and Édgar Rentería; mind you, Varitek, Mueller and Damon were all coming off their historic, first World Series win in 86 years the previous year).

Now, one might assume that the two previous scenarios might pose a bit of a conundrum for Bayliss, who grew up in Massachusetts and was a card-carrying member of Red Sox Nation—and by default, an Evil Empire hater. (I can speak from experience.) But that couldn’t be further from the truth. “That all gets severed,” Bayliss says. By means of explanation, Bayliss tells me that as a Royals minor leaguer, he watched, intently, as his hometown team made its historic run in the 2004 American League Championship Series versus the Yankees (on the shoulders of David “Big Papi” Ortiz)—and then drove 20 hours east from Iowa to Boston and stayed with a buddy in Beantown to watch his team sweep the Cardinals in the World Series. Bayliss remembers, after that last out, running through the streets of Boston screaming, “Johnny Damon for President!”

Domo Arigato, Mr. Bayliss

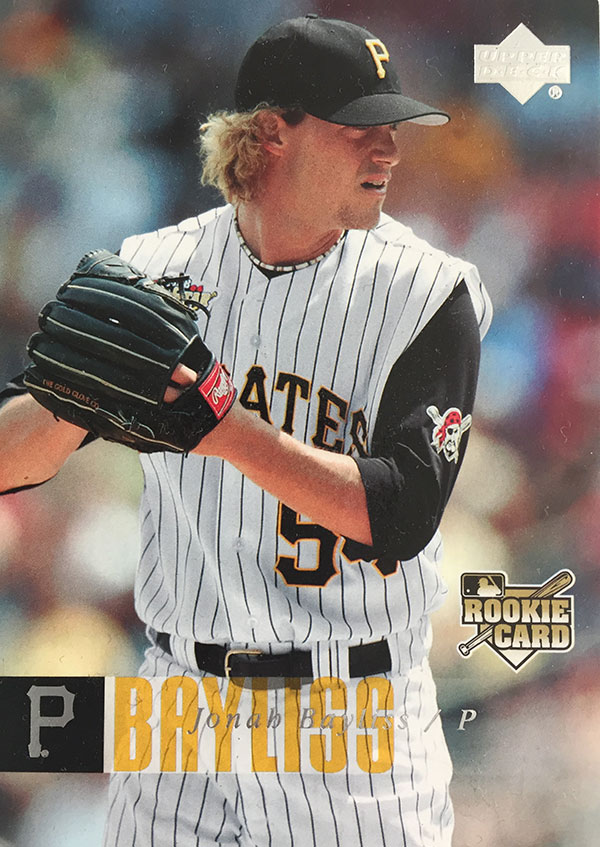

Although Bayliss saw some real high points during that first season in the bigs, 2005 was an altogether forgettable one for Royals fans, as the team ended up losing a franchise-record 106 games (Bayliss ended the year with a 4.63 ERA, having played in 11 games). Then, just like that, the winds changed again; in the offseason, he and another teammate were traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates. For the baseball card hunters out there, Bayliss’ first official appearance in an MLB uniform was in 2006, where he appeared as a Pirate in sets by Topps, Fleer and Upper Deck. (He did sneak into the ’07 Upper Deck set, too.) For one limited edition card for Upper Deck, he tells me he had to sign hundreds—if not, thousands—of tiny pieces of game-used equipment that were later affixed to his card. That same year, at the Pirates’ AAA affiliate in Indianapolis, Bayliss was named the de facto closer. He didn’t follow suit in the bigs (more on that later), but it was still a source of pride After two seasons with the Pirates, he landed in the Toronto Blue Jays’ organization, then in the Houston Astros and Tampa Bay Rays organizations before doing a pair of stints abroad, one in Venezuela and then a three-month jaunt in Japan, where he pitched for the Saitama Seibu Lions.

“Japan is like nothing I’ve ever experienced,” Bayliss tells me. He remembers his translator explaining it to him this way: Japan doesn’t have professional football, basketball or hockey programs of note, so baseball is the sport (besides, maybe, soccer or sumo wrestling)—and fans go absolutely nuts for it. The electricity in a baseball stadium in Japan mimics that of a song-filled, banner-raising World Cup game. “Fans have their own chant for every hitter in the lineup,” says Bayliss. “They chant the chant for the entire at-bat. It’s bonkers.” (Watch this video, if only to get a general sense of the crowd noise—not to watch journeyman Terrmel Sledge get a hit off Bayliss.) There, he reached a level of celebrity that he arguably hadn’t had in the US. When his team’s bus pulled up to its hotel for an away game, for instance, he and his teammates would get the red-carpet, velvet-rope treatment, and when the team entered the lobby, it would be shoulder-to-shoulder with fans, who were presenting gift bags to players and snapping photos. It was like baseball Beatlemania.

If you’re wondering if all the jumping around from organization to organization was taxing on Bayliss, he tells me that it didn’t effect him much at all; he ate it up, in fact. “For me it was never a problem,” he says. “It was a joy. I relished in the fact that I’ve been to every single state except for five,” he says. “When it’s all said and done, baseball’s not really about baseball; it’s about the life, the journey. And I’m absolutely floored and flattered and humbled that I was able to experience different worlds—Japan and Venezuela—little tiny towns in Iowa and Indiana and Idaho. And they paid me to do it.”

Home Sweet Saratoga

In yet another twist of fate, it was at saratoga living‘s neighbor, Uncommon Grounds, that Bayliss was finally hit with the realization that his baseball career was over. Living in Nashville at the time, he and his wife were in town visiting family when he had his epiphany. “It becomes a life thing,” Bayliss says of his decision to retire. “I had a wife and one-year-old daughter and a mortgage and I’m hanging on, playing independent ball. You start to see the writing on the wall.” And it hurt that much more that it had nothing to do with some nagging injury or career-ending Tommy John surgery. “What made it hard [to retire] was that it wasn’t physical,” he says. That led to a bad taste in his mouth, at least at the outset of life away from baseball. “When I first stopped playing, I couldn’t watch a game on TV. I couldn’t watch players that I played with or against, typically, the ones I didn’t like or the ones I didn’t think were very good. I’d see them on TV and think, ‘How are you there?'” He says he’s not in as dark a place anymore, and one rather interesting way he’s been able to cope with life after baseball is by watching the annual All-Star Game, in which a battery of young guns come in, one after another, and all throw 98 mph. “I can’t do that,” he says, with a laugh.

That doesn’t make Bayliss yearn any less for what might’ve been—and you can hear that echo through his response to my question, “If you could change one thing about your baseball career, what would it be?” His answer: “Allowing self-doubt to creep in.” Remember all of those guys Bayliss saw dropping like flies in the minors because of the mental yips? His arrived in 2007. Making the Pirates roster out of spring training that year, he says he remembers feeling like he finally belonged—like, maybe, he was going to be in the majors for the long haul. He got off to a great start as a middle reliever—the type of pitcher who specializes in a late, pre-determined inning of ass-whupping—and by May, he was leading the majors in appearances (i.e. the club had confidence in his stuff). When then-Pirates closer Salomón Torres went down with an injury, Bayliss found himself in the discussion as a possible replacement. But then he had back-to-back crummy outings, and he started to question his confidence—and so did the team’s brass. “From that point forward, it just snowballed, and I can remember being on the mound thinking, if I walk this guy, they’re going to send me down,” he says. Before the team went on the road, making stops in Seattle, Anaheim and Miami, then back to Pittsburgh, he remembers taking a bunch of personal effects—including an electric guitar and amp—out of his clubhouse locker and transferring them to his apartment in Pittsburgh. “I just had that feeling that I wasn’t coming home from this,” he says. And sure enough, after that final game in Miami, he made the trek across the field, walked up the tunnel and found his pitching coach standing at its entrance. Bayliss was summoned to Pirates’ Manager Jim Tracy’s office. He walked in the room, and all the team’s higher-ups were there—Tracy, the pitching coach, the team’s General Manager. Tracy broke the bad news: Bayliss was being sent down. Mind you, he’d been sent down before, but this time, it felt a little different. He remembers not having any reaction, because he’d basically assumed it was coming days in advance. And while that wouldn’t be the last time Bayliss was demoted—of course, the last time was the worst of them all—something changed in him then and there. It was the beginning of the end.

But just like Bayliss said before, in the long run, it wasn’t really about baseball at all. It’s about the journey. Sure, it was a fantastic, decade-long run, peppered with a number of memorable moments—the likes of which few ballplayers ever get to experience—but the life Bayliss is living nowadays seems to be the one that really counts. As of last August, he’s a proud Saratogian, one that’s made a home here with his wife, Austin, and young daughter, Jovi. (He and his wife grew up together in Williamstown and went to the same high school, but were grades apart; they met over the holidays at a local bar in 2005, and ended up getting married in Saratoga at the Canfield Casino.) Bayliss now sells real estate and says that it’s a much tougher gig than throwing heat in the major leagues, though the two have areas of crossover. “It’s all the intangibles you develop along the way; the mental tenacity, the persistence, self-belief, [working through the] complacency issues—it’s all these things. The beauty of baseball is that those things can translate anywhere. My job now is to figure out, specifically, within real estate, where they translate to.”

Whereas I grew up in Saratoga, and it’ll always be a place where I feel at home, Saratoga is, in some ways, more of a place of comfort to Bayliss than it ever will be for me. Sure, it’s the place where he got hitched, with all of those happy memories attached, but it’s deeper, still, than that. “It feels like I’ve found a spot that is alive and vibrant enough to allow me to…” He pauses, searching for the right words, the right phrasing. “…to be something different without forgetting what I was,” he says. Is that like closure? I ask him. “No, I don’t think so,” he says. “Not yet. Here, I meet people from different backgrounds, and it’s almost expected that you’re doing something different now. Here, people are intrigued by [my baseball career], but it doesn’t define me. I seemed to have found a spot where I can kind of let it go but not forget about it.” That last point really resonates with me. Technically, Saratoga stopped being my home 20 years ago when I left it to go away to college; soon after that, my home became the Big Apple and stayed that way until I decided to move back. Now that I’m Upstate again, I feel like one of those people who’s come back transformed, walking the streets here as sort of this stranger in a strange land—but able to finally let go of that old life. That’s the type of stat you’ll never find on the back of a baseball card.