An astounding number of important people and fascinating folks have lived and died in our area.

Over the years, some of their stories have faded; others are murky. Many live on as the names of our hotels, restaurants and historic sites.

As the days darken and Halloween ghosts fly in the night, we dug up some of these tales and tiptoed around a few tombstones.

Here’s what we found:

GRAVES OF GREENRIDGE

Greenridge Cemetery, the oldest cemetery in Saratoga Springs, opened in 1844. Hilly and dotted with tall pines, it’s the final resting place for poets, statesmen, philanthropists, businessmen and several Native Americans.

The cemetery has entrances on Lincoln and Vanderbilt Avenues and is open from dawn to dusk.

George Sherman Batcheller

1837-1908

Yes, George is the gent who built the eye-catching Batcheller Mansion, above, in the heart of Saratoga Springs.

But he didn’t spend much time there, as he was appointed to high government posts in Egypt and Portugal.

His wife, Catherine, died in Egypt in 1903 and was buried there for a year until her body was shipped home and interred in the Batcheller mausoleum, a huge pink granite monument in the style of a mastaba, an ancient Egyptian tomb. George joined her in the tomb after he died in Paris five years later.

Charles F. Dowd

1825-1904

How strange it is that a train killed Mr. Dowd, the Saratoga Springs gentleman known as “The Father of Railway Time.”

Train travel was in full steam across America in 1869 when Dowd was the first person to propose a system of standard time zones for North America.

In 1904, he was walking home at dusk after visiting a friend on North Broadway. A locomotive struck him as he crossed a track and he died instantly.

Sam Hildreth

1866-1929

Hildreth was one of the great thoroughbred trainers of the 20th century.

During his 43-year career, he won seven Belmont Stakes. Twice he won more races in a year than any other trainer in the United States. Nine times, he held the record for the top money-earning trainer, and he held that claim to fame for 60 years. It was shattered by D. Wayne Lukas in 1992.

The co-author of The Spell of the Turf, about the history of American horse racing, Hildreth lived at 28 Union Ave. in a Queen Anne-style mansion that is now the Empire State College Foundation.

He died at age 63 and was posthumously inducted into the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in 1955.

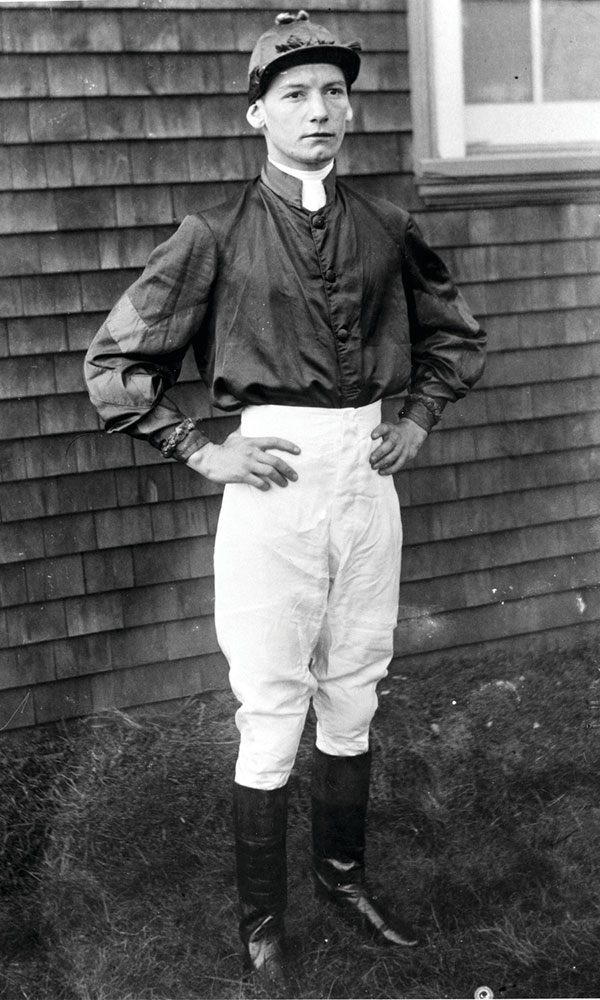

Buddy Ensor

1900-1947

Thoroughbred jockey Buddy Ensor set the world on fire when he was still a teen.

In 1918, he won the Saratoga Special Stakes and a year later, the Travers Stakes. He won five races in a single day twice, in two years.

But Ensor, who lived in Saratoga Springs, got into trouble when alcohol abuse and misconduct got him kicked out of the Jockey Club.

E. Lavelle “Buddy” Ensor died in 1947 and was posthumously inducted into the National Racing Museum and Hall of Fame. He’s buried next to his wife Daisy.

Katrina Trask

1853-1922

The grieving mother and writer who dreamed up Yaddo, an artist’s retreat on her Saratoga Springs estate, is buried in the woods beyond her mansion, at a place she picked out three-and-a-half years before her death.

Lady of Yaddo, a book based on Katrina’s memoirs by Lynn Esmay, tells us that Katrina, whose four children died at young ages, found the spot while she was walking with a Greek archbishop from Syria. Katrina and her friend both felt a mystic presence, a sense of peace, on this hillside.

She called the place “Holy Hill” and named a “circle of friends” who she hoped would rest there with her in body or spirit.

Katrina’s humble gravestone is surrounded by five, undated pink granite markers. George Foster Peabody, her second husband, is buried there. There’s a marker for her first husband, Spencer Trask, but he and their children are buried in Brooklyn.

Go for Wand

1987-1990

Oct. 27, 1990 was a heartbreaking day in the world of thoroughbred racing. That’s when the champion Go For Wand took a nasty fall at the Breeders’ Cup at Belmont Park and was euthanized.

The ill-fated filly is buried in the infield at Saratoga Race Course, the site of two of the greatest triumphs of her short career: the Test Stakes and Alabama Stakes.

Go for Wand is not the only horse buried at the track. Fourstardave, Mourjane and A Phenomenon were laid to rest in the Clare Court area on the backstretch at Saratoga.

Jane McCrea

1752-1777

Poor Jane. Not only was she killed while on the way to visit her boyfriend, but after her death her body was moved three times.

Blame it on the Revolutionary War. Jane was in Fort Edward, en route to Fort Ticonderoga, when an advance party for British commander John Burgoyne, led by Huron-Wendat warriors, ambushed the village.

How Jane died is a mystery. According to legend, she was scalped. In another story, she was hit by gunfire from Americans pursuing the warriors. The scalping tale became propaganda for the patriots. In some accounts, her hair was flaming red and three-and-a-half feet long.

In 2003, when her body was exhumed, her skull was missing. Today, Jane rests in peace (we hope) in Fort Edward’s Union Cemetery.

Lemuel Haynes

1753-1833

In the Washington County town of Granville, you’ll find the grave of the Rev. Haynes, who started life as an indentured servant doing farm work. He later made history as the first African-American ordained in a mainstream Protestant church and the first African-American to receive an advanced college degree.

Born to a Caucasian mother and a father who was of African descent, he was a minuteman in the Revolutionary War. After the war, he was known for his writings against slavery.

Rev. Haynes served the all-white congregation at Rutland’s West Parish Church, now West Rutland United Church of Christ, for 30 years. In 1804, he received an honorary master of arts degree from Middlebury College.

After his death at age 80, he was buried in Lee-Oatman Cemetery. The Lemuel Haynes House in Granville is a National Historic Landmark.

Ulysses S. Grant

1822-1885

The remains of our 18th president and his wife, Julia, are in New York City, in Grant’s Tomb, the largest mausoleum in North America. But the actual bed upon which the famous Civil War commander took his last breath is a few miles from Saratoga Springs, in a tiny cabin on top of Mount McGregor.

For more than 130 years, the room where Grant died of throat cancer has been carefully preserved. At the U.S. Grant Cottage Historic Site in Wilton, even his funeral flowers, dry and colorless, are on display.

When Grant was diagnosed with cancer in October 1884, he started writing his memoir in New York City. In the spring of 1885, his friend, Joseph Drexel, who built the Balmoral Hotel on Mount McGregor and the narrow gauge railway that took people from Saratoga Springs and up the mountain, offered his private cabin to the ailing president.

The 63-year-old Grant spent his final six weeks in the cottage completing his memoirs, before his death on July 23, 1885.