In August of 1992, I learned that John J. “Jack” Wilpers, Jr., a US Army intelligence officer–turned–CIA employee who played a key role in the arrest of former Japanese Prime Minister General Hideki Tojo just nine days after the formal end of World War II, was a Saratogian. As an Albany-based reporter (who would later become a long-time Saratogian myself) for the Associated Press, I then spent the next 18 years trying to get the veteran to talk about what happened on September 11, 1945, without avail. It wasn’t just me—Wilpers’ lips were sealed to everyone, including his wife and five children, one of whom was a journalist himself. But thanks to a chance encounter on a Massachusetts beach involving a nasty impending storm and a Saratoga Race Course giveaway baseball cap, I finally got my interview.

Let me back up.

Wilpers was born in Albany in 1919, and moved with his family to Saratoga as a boy (“Dad was a bookie,” he would eventually tell me, and his mother ran a tea room next to McGregor Links). Wilpers graduated from St. Peter’s Academy in 1937 and joined the Army, which brought him to New Guinea, the Philippines and, obviously, Japan.

For the non–WWII historians amongst us, Hideki Tojo was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army and served as the country’s prime minister from 1941 to 1944. He oversaw Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor before falling out of favor with Japanese Emperor Hirohito in 1944 and being forced to resign. Shortly after Japan’s surrender following the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, US General Douglas MacArthur ordered Tojo be found and taken into US custody as a war criminal. That’s where Wilpers, then a 25-year-old Army intelligence officer, comes in.

Sixty-five years after what Wilpers refers to as “the Tojo incident”—the capture of the former prime minister that he played a starring role in—the veteran received a belated Bronze Star medal from the Army for his actions during Tojo’s arrest. It was then that Wilpers finally broke his silence, in a 2010 Washington Post story about his being honored by the Pentagon.

I didn’t learn about the Post story until late August of that same year, when it popped up as I Googled Wilpers’ name to find out if he was still living. Seeing that Wilpers had finally talked to a major media outlet about the Tojo arrest, I decided to give him another call on the chance he would agree to an interview with an AP reporter from his old stomping grounds.

But that would have to wait until I returned from my annual vacation on Horseneck Beach in Westport, MA.

It was the week before Labor Day, and a tropical storm was making its way up the Eastern Seaboard, headed straight toward the southern New England coast. Mandatory shoreline evacuations were expected, so I would have to leave my beachfront rental a day earlier than planned. I decided to spend part of my last full day, a Thursday, on a stretch of beach I rarely visited.

While sitting on the sand watching the surfers taking advantage of the big waves kicked up by the approaching storm, I noticed that one guy walking by with his surfboard was wearing the same flat track hat I had on: the khaki one from 2004 with the Saratoga Race Course clubhouse awning logo embroidered in red.

I struck up a conversation. He said he had relatives who used to live in Saratoga and owned a couple of businesses, but that was years ago. I asked him his family’s name.

“Wilpers,” he said.

“Tell your old man I’m still pissed off at him for not talking to me about Tojo,” I said.

It turned out that the surfer was John Wilpers, the oldest of Jack and Marian’s five children. John, a journalist-turned-media consultant, lived outside Boston and was vacationing in Westport with his wife and two daughters.

After explaining who I was and telling him I planned to call his father when I returned home from vacation, we parted ways. The following Tuesday morning, I called Jack Wilpers at his home in Garrett Park, MD. He didn’t hang up on me as he had done several times before. I mentioned meeting his son on the beach in Westport. He said John had alerted him that I would be calling for an interview but, at 91, he didn’t think his memory was all that good.

His memory was fine.

For about 90 minutes over the next two days, Jack Wilpers provided details of his early life, his wartime service and Tojo’s apprehension, itself a bizarre series of events that unfolded inside the ex-prime minister’s Tokyo home before a gaggle of reporters and photographers from some of the world’s biggest news outlets, including the AP, United Press International and The New York Times.

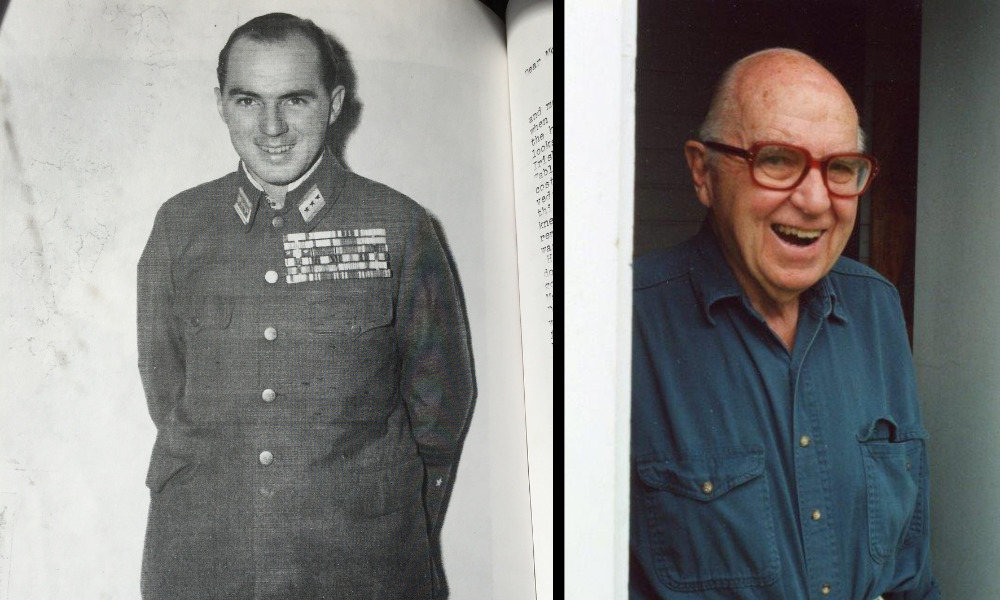

The story: The Army had followed journalists to a home in a Tokyo suburb. (“The best way of finding Tojo was to find our own US newspaper people, because they were there well ahead of us,” Wilpers told me.) Standing outside the home of Tojo, the group heard a gunshot inside and Wilpers, with the help of a fellow officer, busted down the locked front door. They found Tojo slumped in a chair, blood flowing from a self-inflicted gunshot wound to his chest. In filed the press members—one of whom, Sergeant George Burns of Yank Magazine, just so happened to be an Albany Times Union photographer before the war. Burns shot a now-famous photo of Wilpers, his Upstate New York neighbor, picking up the handgun the retired general had used to shoot himself in the chest.

Tojo ended up surviving his suicide attempt; an Army medical team arrived, stabilized the former prime minister and took him to a military hospital, where he recovered. His trial for war crimes started in 1946 and lasted two years, ending in his conviction. He was executed by hanging in a Tokyo prison in late December 1948, by which point Wilpers was already back home, a year into what would be a 28-year career with the newly founded CIA—and a 65-year career of keeping quiet about the capture.

Following our conversations in 2010, I never spoke with Jack Wilpers again. I did, however, keep in touch with his son John, who in early 2013 informed me that his dad’s health was failing. Jack died that February 28 at the age of 93. I wrote his obituary for the AP’s national and international wires.

Would Jack Wilpers have talked to me if I hadn’t met his son on the beach that day? Possibly. Regardless, the journalism stars aligned on September 2, 2010, the 65th anniversary of the end of WWII. Of the thousands of stories I wrote over my 31 years spent with the AP in Albany, the Jack Wilpers story is among my favorites. He had played a key role in the arrest of one of the most infamous Axis leaders of WWII, a man blamed for the deaths of millions across East Asia and the Pacific. Finally getting Wilpers—a fellow Saratogian—to talk in detail about that day and sharing it with a global audience (more than half the world’s population sees AP stories every day) was a highlight of my career. And it was all because of a free Saratoga Race Course hat.