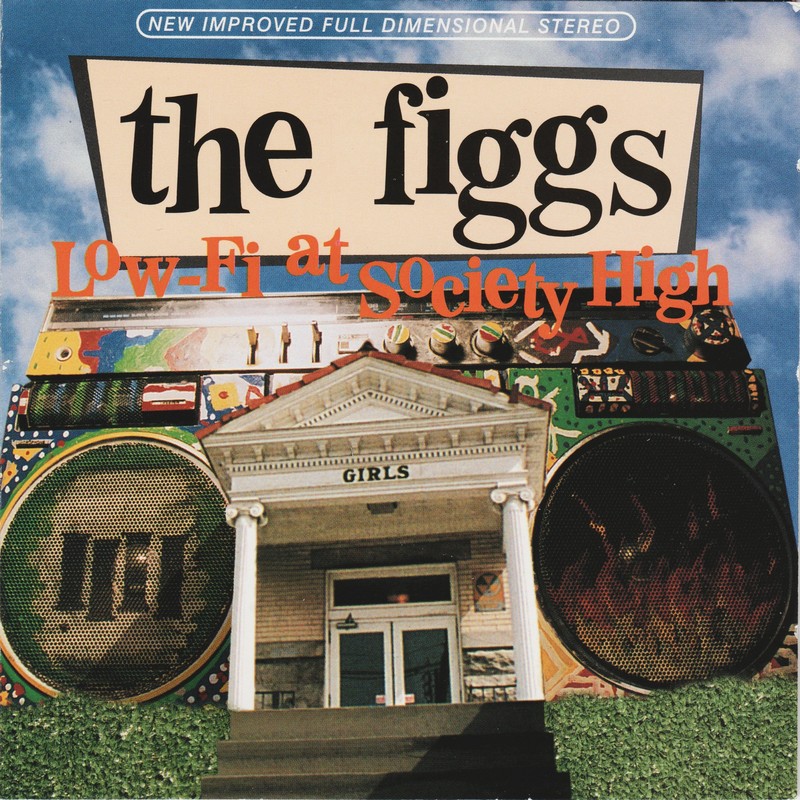

I was 14 years old when my older brother, two years my senior, first brought home The Figgs’ 1994 album, Low-Fi At Society High. As it was with every CD my brother owned in those days, he listened to it obsessively, so much so that his high school band began covering tracks from it. The album had that much of an immediate impact on him. (If my memory serves me, his three-piece band did versions of “Favorite Shirt” and “Stood Up” at Saratoga Springs High School’s “Battle of the Bands” in ’94 or ’95.) Like any younger brother in need of his older brother’s approval, I began borrowing Low-Fi for various stretches of time—and quickly became a mega-fan.

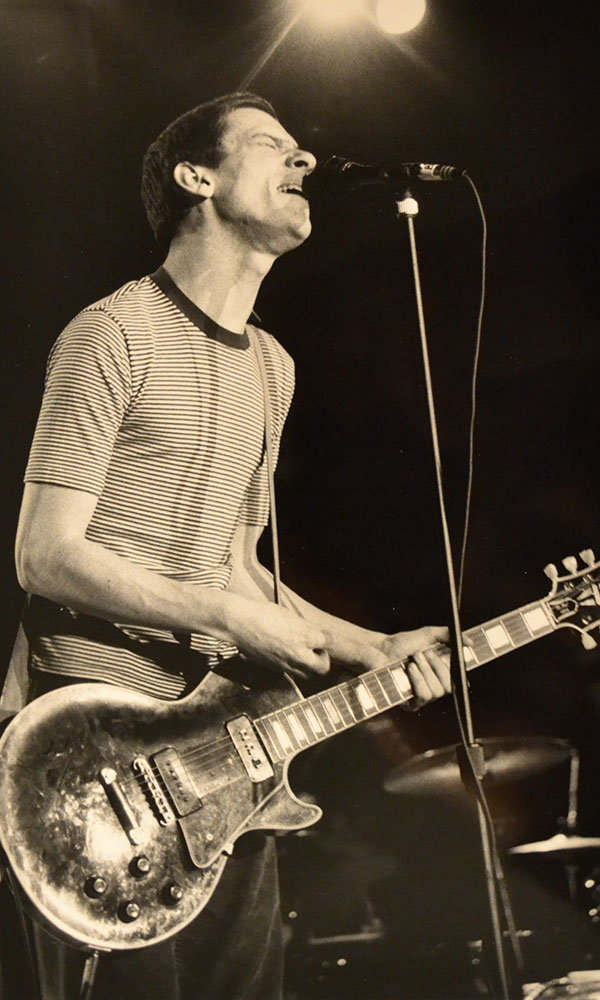

Growing up in Saratoga Springs, The Figgs were royalty, because they were our band. Sort of how you’d expect New Jerseyans to feel about Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band or Bostonians, Aerosmith. Three of The Figgs grew up in Saratoga—Pete Donnelly (bass/vocals), Mike Gent (guitar/vocals) and Guy Lyons (guitar/vocals)—and the fourth, Pete Hayes (drums), was a Skidmore College student. They wrote their own songs and had amazing influences (Elvis Costello, The Kinks, The Rolling Stones), but still had their own distinctive sound.

To honor the 25th anniversary of the band’s breakthrough album, Low-Fi At Society High, which hit record stores on June 28, 1994, I’ve assembled an expert panel—including all of the original members of the band (and many others)—to provide insight into the lead up to and making of the record, and its aftermath. You can find a shorter version of this feature in the Summer Issue of saratoga living magazine; someday, you may even find a longer version of this, in book form, on the shelves at Northshire Bookstore. But until then…

***

At 46, Pete Donnelly, who’s been in the band since its inception 32 years ago, is the baby of the group. Growing up on Circular Street in Saratoga, Pete was the lone Donnelly sibling born in the city (he has two older brothers, Phillip and Stephen, and an older sister, Jane, all of whom were born in Ann Arbor, MI). His father, Denis, had ventured to Saratoga in 1970, after landing a job as a physics professor at Skidmore College; his mother, Jackie, also worked at the college as an editor. (His father wouldn’t receive tenure and ended up at Siena College in nearby Loudonville, where he’s worked the duration of his career.) Says Donnelly of his earliest musical training: “There was a piano in the house, so it was [my] first instrument. As my brothers brought home instruments, they really didn’t want me playing their stuff, so my dad got me a bass,” he says. He got it as a gift for his 13th birthday. As it were, the Donnelly boys were all into music: Steve bought a guitar from Phil’s friend, and Phil played a little guitar himself. Just a handful of years later, Donnelly would be attending Saratoga Springs Junior High School, where he’d realize that “if you play bass, you’re in everybody’s band.” To wit, he found himself in several projects, as well as the high school jazz band, where he met future Train drummer Scott Underwood. (At one point later on, Underwood landed Donnelly an audition for Train; it didn’t pan out.) It was at Saratoga High that Donnelly also met the two fellow musicians and upperclassmen, Mike Gent and Guy Lyons (both class of ’89), that he’d later form The Figgs with.

Gent’s family moved to Saratoga from New Jersey in 1983, settling on the south side of town on Jackson Street, when Mike was in seventh grade. The son of a stay-at-home mom and dad, who worked for the local electric company, Gent entered Saratoga’s junior high a month or two into the school year, so he was “the new kid” and didn’t have any friends. He soon met Lyons in social studies class and Guy’s older brother, Reid, at the local grocery-store-slash-unofficial-south-side-kid-hangout, 5 Points Market. (I can attest; I bought tons of candy and baseball cards there throughout my youth, while my parents played softball with their Skidmore colleagues at the nearby South Side Rec.) The Lyons brothers lived on Vanderbilt Avenue on the south side, too, and were budding musicians, so it made sense that the trio of boys would become friends, start hanging out and jamming. Lyons tells me that Gent’s father was a huge music fan, who played guitar and had a sizable record collection. He ended up being a “huge influence” on the young musicians.

Lyons actually got turned onto playing the drums in 8th or 9th grade by Gent, who had a drum kit at his house and played them before he switched over to the guitar. Unfortunately, the two boys had a bit of a falling out early on, which is how Lyons ended up meeting Donnelly and playing with him instead. The two rhythm section players hit it off and locked in, plotting to form a band in the vein of the rhythm-centric ’80s California punk stalwarts, the Minutemen, which featured a bassist/vocalist. Eventually, Lyons and Gent reconciled and began playing again, not with Donnelly, but rather, Lyons’ older brother, Reid. Soon, though, came the fateful band practice when Reid couldn’t make it, leaving Lyons and Gent in the lurch. They called up Donnelly to see if he’d be able to fill in.

Of course, that day, the stars were finally aligned. Donnelly and Gent both remember that the first song on the first day the trio ever played together—and really locked in on—was Jimi Hendrix’s “Fire.” Donnelly had never actually played the song before, but in that moment, “it just made sense,” and the trio immediately tapped into that shared energy and chemistry and founded a band called the Sonic Undertones. It was 1987. The band played its first official show opening for a Donnelly-Lyons brothers punk-metal supergroup called Human Slug, which did covers of songs by Black Flag and Hüsker Dü, with some originals peppered in. At that point, Lyons was the young band’s lead singer, songwriter and frontman behind the drums—like the ’70s band The Romantics—with Gent and Donnelly, the melodic core (Gent was also a capable second vocalist and songwriter). Donnelly had been dabbling in progressive jazz-punk instrumentals à la The Minutemen, so his bass-playing style was still evolving, and he hadn’t yet begun singing; Gent, on the other hand, was already an accomplished guitarist and rock-and-roll sponge, “singing and playing better than anybody [else],” says Donnelly. “Mike had a better voice than Guy, but Guy was loaded with personality,” says Donnelly of Lyon’s early turn as frontman. “The three of us were ripping right away.”

About a year into being a rock band, Gent, Donnelly and Lyons—the latter two of which had been veterans of the Saratoga Guitar Workshop, which was a meet-up for like-minded local musicians run by local guitarist, producer and Skidmore’s Artist-in-Residence John Nazarenko—took the best songs that they’d written into Nazarenko’s home studio and did a limited-release cassette tape entitled Put Me Up on the producer’s Flat Cat Records label in 1988. “He was the first adult musician that took notice of us,” remembers Gent. The album featured nine originals, and was released under the Sonic Undertones moniker. (One of Donnelly’s pre-Sonic Undertones bands had been put together by Nazarenko and was called The Initials, who played the local “Battle of the Bands” circuit at high schools; the band also featured Chad Tallman, Owner of Saratoga bakery, The Bread Basket.)

The following year, the band weathered its first major lineup change when Lyons, who had been struggling during his senior year of high school but had ultimately graduated, decided to enlist in the military. “I wanted to experience some things outside of my hometown,” he says. “I’d always been a fan of military history and read a lot of books about that stuff, and I wanted to be a part of it.” He’d end up becoming a Tracked Vehicle Repairman in the United States Army—basically, the guy that follows behind tanks and armored personnel carriers and makes sure they’re in fighting order. He’d end up fighting in the Persian Gulf War and was stationed in Germany when the Berlin Wall fell. Lyons was gone by August 1989.

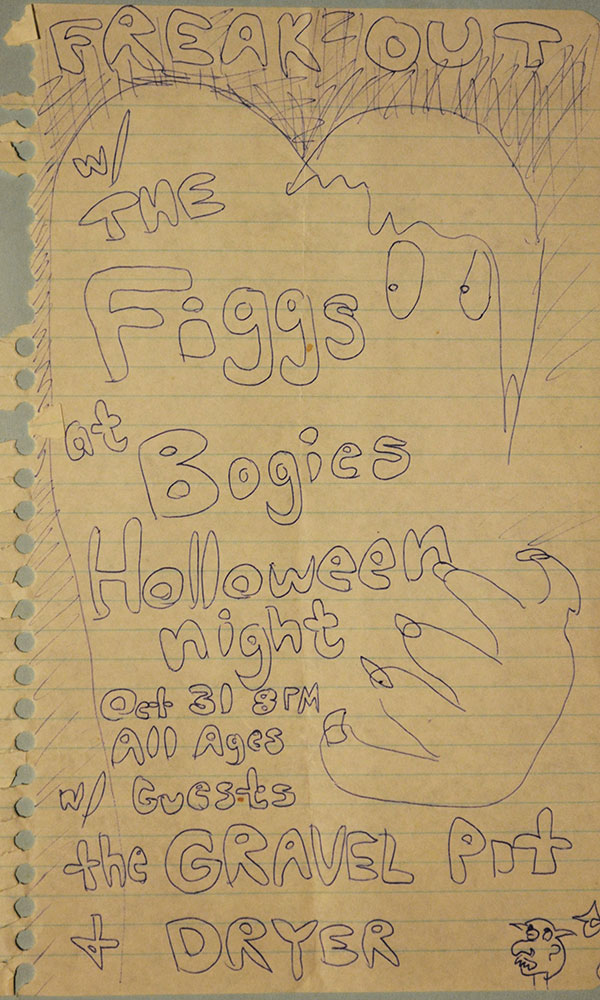

Of course, Lyons’ departure from the band left a gaping hole in the lineup; he was half of the rhythm section and the de facto frontman, lead vocalist and songwriter. Luckily, Gent had no interest in going off to college following graduation and was waiting in the wings to pick up lead vocal duties in the band. By then, Donnelly, who still had a year left in high school, had started penning his own songs and had found his singing voice. But they still needed to find a drummer, and they tried out a few, but nothing seemed to pan out. Fill-ins included the aforementioned Underwood (who would later win a Grammy with Train), as well as local Dorian Crozier, who would go on to become a sought-after session drummer for artists such as Miley Cyrus, P!nk and Joe Cocker (he was also in the lineup of Five for Fighting, when the band was nominated for a Grammy). So clearly, they had good taste in skinsmen. Maybe to distance themselves from the previous trio—or just to up the “cool” ante a bit—the band, had now officially changed their name to The Figgs. (Says Gent of how the new name came to be: “Donnelly, Guy and I were in Guy’s mom’s front living room and had decided to change the name, because we had been told by this small label, who were briefly interested in the band at the beginning of 1989, that we would need to change our name, which was just a combo of two bands that already existed [you know which ones]. It made sense to us. I thought we should just shorten it to SU’s, but of course, this didn’t fly with the other two. We then wrote a big list of bad names and ‘The Figgs’ was picked off the list, I think because it fit into what we were trying to do at the time which was mostly pop, like The Raspberries. I’ve always thought it was a lame, terrible choice, and has maybe turned a lot of people off to wanting to check out the band over the years, but it’s what we are stuck with. I’ve never been comfortable telling people when they ask the name of the band, but hey…who cares what I think!”) That Halloween, The Figgs played a show with another local band, Cement Bunny, which featured Hayes on drums, and that night, Hayes tells me, he’d decided to show up to the gig adorned in a soup-can necklace. Covertly, Hayes tells me, Donnelly and Gent were “auditioning” him for their band. Hayes had actually heard The Figgs play beforehand and had wanted nothing more than to be in the band. And after a second, more formal audition in Donnelly’s basement, Hayes had his wish come true.

Before matriculating at Skidmore and becoming an honorary Saratogian, Hayes had grown up in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, though his grandparents had lived in nearby Washington County, and he’d spent quite a bit of time in and around Saratoga as a kid. The oldest member of the band (he’s four years Donnelly’s senior), Hayes had also been a musician the longest of anyone in The Figgs, playing the drums since the third grade and getting his first real drum kit in the eighth grade. By that point, he was absolutely obsessed with playing, and his after-school regimen consisted of watching General Hospital and the movie that followed—and playing drums for the rest of the day. “I didn’t have any friends over for that entire year,” says Hayes. Being the elder Figg also meant that Hayes had a much busier personal schedule than the rest of his bandmates: The year he joined The Figgs, he was playing in a second band on the side, working a pair of jobs in town and taking a full course-load at Skidmore. (Interestingly, Hayes was in my dad’s English class—”Shakespeare’s Tragedies”—and after getting a poor grade for the semester, decided it was time to focus more on his drumming skills. So my dad indirectly helped The Figgs get serious. Despite the bad mark, Hayes eventually graduated from Skidmore in 1991.)

***

Once Donnelly graduated from high school in 1990, he applied to and got into Skidmore, getting a free ride, because his mom still worked there. That put two members of the band on campus, and even though Gent wasn’t officially a Skidmore student, he tells me that the college became his main hangout and one of two unofficial band hubs (more on the second one in a minute). Gent remembers rehearsing all over campus, wherever the band could fit their equipment—including a closet at the college’s athletic center. At this point, The Figgs were really only booking shows in the Capital Region, with the vast majority of them taking place in Saratoga at private residences, the local high school and venues such as Caffè Lena, the Bijou, Our Place Pub and Skidmore’s on-campus pub/venue, Falstaff’s. They also headed southbound to play Albany venues such as QE2 and Bogie’s, the latter becoming one of their mainstays. All along, The Figgs continued writing songs and perfecting their sound, which at the time, was sort of an amalgam of early Elvis Costello and punk rock, with more than a few nods to British Invasion bands, such as The Rolling Stones and The Kinks. They’d also started working with Brad Morrison of Absolute A Go Go Records and Miracle Management, in 1990, recording with him. Two years later, he’d be their manager—and he later helped them get their first big break.

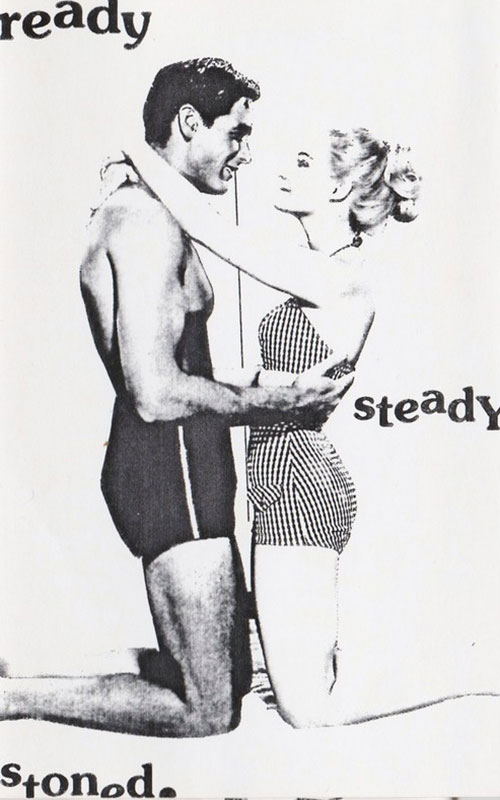

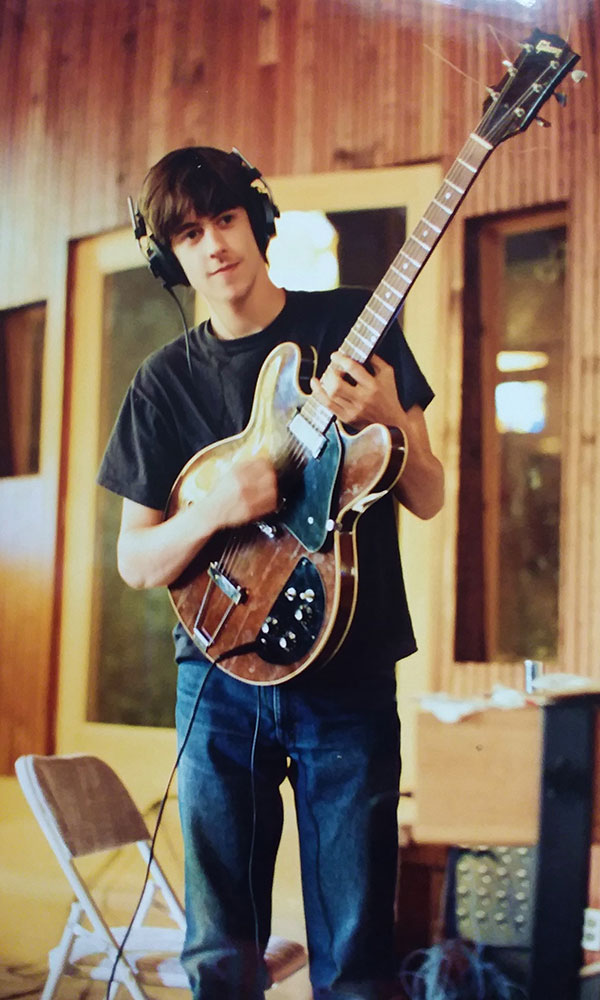

Between 1990-93, the band wrote and recorded three albums’ worth of tracks, which it would release on a 7-inch and two separate cassettes. The two-sided single, released in 1992 on Absolute A Go-Go Records, was anchored by the song “Happy,” with a B-side of “My Mad Kitty” (a Green Pajamas cover). Their self-released cassette tape, Ginger, which the band hand-designed and -numbered to 500 (now a sought-after local collector’s item and rumored to be getting the deluxe reissue treatment soon), landed the same year and featured ten tracks, including one by former Sonic Undertones bandmate Lyons. Speaking of which, after three years and one month in the service, Lyons was honorably discharged from the Army, having been awarded three medals. More important to Figgs’ lore, while Lyons was stationed abroad in Germany, he spent $400 on a 1963 Gibson Melody Maker and a ’60s Deluxe Reverb amp, which he bought from a fellow soldier. Instead of returning to the states a drummer, he came back a guitarist, taking up the instrument and never looking back. “I don’t exactly know how I wound up playing with [The Figgs again],” says Lyons. “Mike wanted to have a two-guitar band.” Lyons says his role evolved into being the band’s lead guitarist, with the side task of being band “organizer.” (When pressed on what this means, he says, for example, he helped track down the band’s new van.) After returning home, Lyons enrolled for a brief stint at Adirondack Community College and took a guitar class there. In his free time, he noodled around on the instrument, attempting to figure out “new melodic guitar parts” to add to the already penned Gent-Donnelly tunes. His goal was to always figure out “something different” from what Gent was playing. He officially rejoined the band in ’92 and was part of the sessions for Ready Steady Stoned (1993), also a cassette tape the band released on Absolute A Go-Go. It included an all-Donnelly-Gent battery of tracks, with the exception of one co-write by drummer Hayes (“Lynette”). With Lyons back in the fold, The Figgs’ sound and energy were cranked up to 11. It didn’t hurt that the band had been playing together for six years now and had two full albums of music on the street.

Some of the songs that ended up in the band’s repertoire were originally demoed at the band’s other major hub, 36 Franklin Street, a four-bedroom house in Saratoga, which doubled as the bandmates’ living quarters, rehearsal space and had, historically, been an off-campus Skidmore party house. The first Figg to discover the place and move in was Hayes, and then, when Lyons returned from the Army, he moved in. “I actually lived there before I officially moved in,” adds Gent. When Hayes was living there alone, says Gent, he “crashed on the couch for an entire winter.” They’d assembled a small studio out of one of the bedrooms, and since Gent wasn’t enrolled in college or working a day job at the time, he would just write and record songs all day long. He eventually found his own place on Broadway above Wheatfields Restaurant & Bar, but by early 1993, the band started looking for its own unofficial headquarters, and all of the rooms were open at Franklin Street, so the four Figgs swooped in. “That year, ’93, the four of us living there and writing and rehearsing and partying and having a blast…I remember [that year] being a very fun time with the band,” says Gent. Things would only get more exciting that Halloween, when they would play a show that changed their lives forever.

In the months leading up to the Halloween gig, The Figgs expanded their gigging horizons beyond the Capital Region. They played to packed houses in Massachusetts, Vermont and Connecticut, as well as at least one show at the New York City indie haunt, The Knitting Factory. And then The Figgs’ manager struck gold. As the story goes, Matt Aberle, the West Coast A&R man—basically, a talent scout and in-house manager—for a relatively new, BMG-backed East Coast record label, Imago Records, caught wind of the Saratoga band and was immediately enamored. Aberle had worked at Morgan Creek Records, which produced soundtracks for blockbuster films such as The Last of the Mohicans and Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, and had been poached by Imago founder Terry Ellis, who had made a name for himself in the ’60s and ’70s as a record producer, talent booker and all around music raconteur. Ellis had co-founded a catchall company, Chrysalis, as well-as a same-named record label. (Acts Ellis had ties to throughout his incredible career included Led Zeppelin, David Bowie and Jethro Tull.) Back in his Morgan Creek days, Aberle had signed a band called Miracle Legion, which had previously been managed and developed by The Figgs’ manager. Once Aberle turned up at Imago, Morrison reached out to him, name-dropping Miracle Legion, and then saying he was working with The Figgs and that he wanted to send Aberle their demo. Aberle was interested. “He sent me the demo and a 7-inch single [1992’s Happy], and I just loved it,” says Aberle. So Aberle brought the band to New York City to play a private session for him and Ellis, at a rehearsal space called S.I.R. studios on West 25th Street. “I was just like holy shit,” says Aberle. “To me, it was [like hearing] The Beatles. I know that sounds ridiculous, but when Mike and Pete sang together…you have Pete Donnelly, the cute guy, who plays the bass. It’s like straight out of central casting. All [he’d have to do] is play lefty [on a] Hofner bass, and he’d be McCartney. And then you had Mike, who was like John Lennon, who’s aggro, with an attitude, but when they sing together, it’s like magic.” He walked out of the session ready to sign them on the spot, but Ellis wanted to see how the band performed in front of a live audience. Fast-forward to Halloween night 1993, when the band played a sold-out gig at Bogie’s in Albany, with Aberle and Ellis in attendance. Donnelly’s family was in attendance, his dad, Denis, shooting a VHS of his son’s performance. “It was peak power and fandom for them in Albany,” says brother Phil Donnelly. Afterwards, Imago’s boss needed no further convincing. The label signed the band soon after.

At the time, Imago was no small-potatoes label; it had a lineup that included Aimee Mann (of ‘Til Tuesday fame), the Rollins Band (featuring seminal DC punk heavyweight, Henry Rollins), a pre-Dawson’s Creek-theme-song-fame Paula Cole and even hit Australian pop star, Kylie Minogue. “We felt like we weren’t going to get lost in a huge stable of artists and bands,” says Gent. “They [only] had a handful of people on the label, so [we felt like] somebody there was going to pay attention to us.” Imago’s plans for breaking The Figgs leaned heavily on touring and targeting the band’s music at college radio stations.

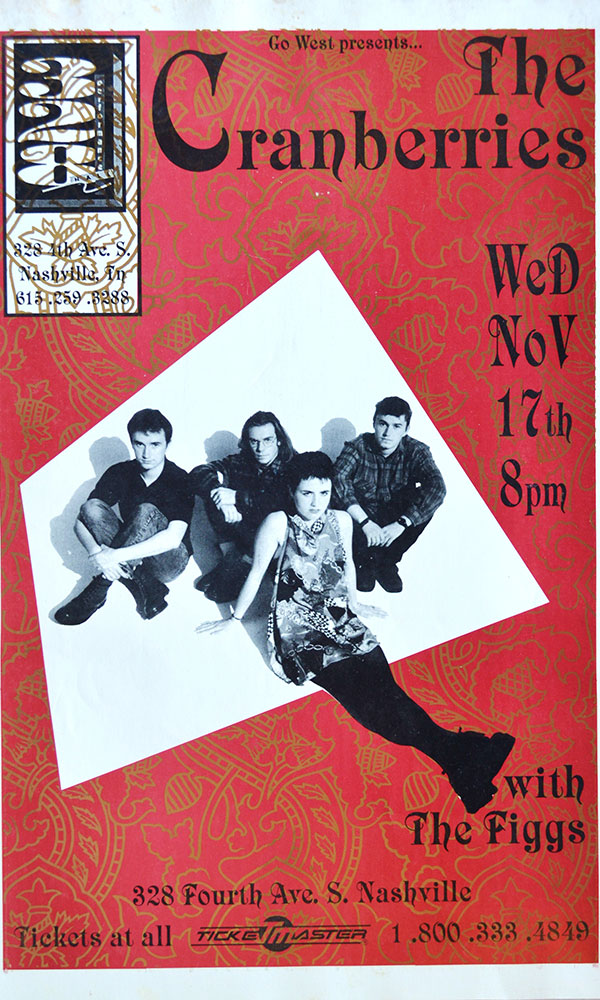

On the touring front, Imago’s plan was to get the band out of their comfort zone a bit and in front of new audiences and hope that something stuck. And without the label having to lift a finger, the band was handed a major opening slot on a buzz-worthy tour just a few days after that Halloween show in Albany. On November 4, The Figgs found themselves in New Jersey, opening for Irish alternative-rock band, The Cranberries, whose debut, Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We?, was blowing up all over the states, due to singles “Linger” and “Dreams.” Several days later, The Figgs opened for them at the vaunted Hammerstein Ballroom in Midtown Manhattan. “It was great for the band’s ego,” says Donnelly, who at this point, had quit college to focus full-time on music (he wouldn’t get a chance to complete his Skidmore degree until 2017). “The [Cranberries] tour had nothing to do with our deal with Imago; our manager had sent some of our music to a rep at Rough Trade [Records] in London, and The Cranberries were looking for an opener quickly, and somebody we know played it for them, and they picked us. Dolores [O’Riordan] herself picked us for that tour.” Donnelly remembers spending a night on The Cranberries’ tour bus, and the two bands becoming fast friends.

So right out of the gate, not only had The Figgs presented an easier sell for Imago because of their built-in fan base, but also had practically done the label’s job for them by getting on a major concert tour all by themselves. Not surprisingly, that endeared The Figgs to Imago’s brass. “[Our] relationship with Imago was very copasetic right from the beginning,” says Donnelly. And the details of their record deal speak volumes for the trust between the two parties: The band signed a seven-record deal, with a clause in the contract allowing them to release three singles, independent of the label, per year.

To get The Figgs the airplay they deserved, the label sent them into the studio to cut their first real, well-financed studio album. In February 1994, the quartet convened at Dreamland Studios in Woodstock, NY, to record what would become Low-Fi At Society High. The label had connected them with Don Gehman, who was best known for producing John Mellencamp’s American Fool, which features the artist’s best-known hit, “Jack and Diane.” More immediately relevant to the members of The Figgs, however, was the fact that Gehman had been in the control room for R.E.M.’s Lifes Rich Pageant (1986), one of the albums that helped the Athens, GA, band go mainstream. (Hayes admits being in Gehman’s presence made him feel “awestruck” and “nervous.”) Had you been a diehard Figgs fan seeing the band’s track listing at Dreamland, you’d have probably known most of the songs that ended up on Low-Fi. Some, even, by heart. “Wasted Pretty,” for instance, dated back to the Ginger sessions, where it was a much grungier and distorted sonic soufflé (it had been penned by Gent while he was still living at home with his parents). A number of tracks were also from the Ready Steady Stoned sessions: “Stood Up!,” “Chevy Nova,” “Jump Start” and “Favorite Shirt” appeared on the original cassette tape release; and outtakes included early versions of “Cherry Blow Pop” and “Ginger.” That’s seven out of the 15 tracks on Low-Fi right there. At least to the band, what ended up being Low-Fi was more of a mixed tape or “greatest hits” record than a set of new songs. “I remember not being thrilled,” says Gent. “I wanted Low-Fi to be all new stuff that had never been released. I don’t know if the rest of the band were feeling the same way, but I was kind of bummed that we were going to go back and re-record some of that stuff. Because some of the songs we’d recorded more than once.” Donnelly also says that there was a phantom, unreleased album recorded right after Ready Steady Stoned, which featured “Step Back, Let’s Go Pop,” “Tint,” “Shut” and “Asphalt,” all of which ended up appearing on Low-Fi. And “Waltz for Bob” was in the band’s setlist at the big Bogie’s show on Halloween, so really, the only technically brand-new tracks were “Slowdown” and “Charlotte Pipe.” (As Gent notes, despite some of those tracks being recorded in previous sessions and debuted live, at the time, “Asphalt,” “Slowdown,” “Charlotte Pipe,” “Waltz for Bob” and “Tint” would’ve all been new to the majority of fans.)

That March, Gent and Donnelly flew out to Los Angeles to mix the album with Gehman. Lyons and Hayes weren’t invited, so they hung back in Saratoga for most of the time. Hayes spent some of the downtime in London with Morrison and had a chance to sit in on a studio session in Oxford with The Figgs’ new friends, The Cranberries. (He tells me he was brought into the control room and heard an early version of the band’s future smash hit, “Zombie,” which would appear on their follow-up album, 1994’s No Need To Argue.)

The resultant album featured 15 tracks that clocked in at 42 minutes and 25 seconds, and was littered with short, sharp pop songs. (A&R man Aberle was ecstatic with the results.) To put that into perspective, there were three sub-two-minute songs, five sub-three-minute songs and six sub-four-minute songs. In short, it had all the makings of being “radio friendly.” The longest track, “Tint,” clocked in at 6:56, and was buried all the way at the end. In order to market it, a debut single needed to be chosen from that track listing, and for all intents and purposes, the label had it all figured out. (Donnelly notes that “[The band] had no preconceived notion about what the [first] single would be. None.”) Imago was all over the seven-year-old, Gent-penned “Wasted Pretty,” which fit perfectly into the à la mode soft-loud-soft-loud format of songs of the moment. So the label set up the band with video producer on the rise, Jesse Peretz, who had just produced a trio of videos for his former band The Lemonheads and would go on to work extensively with the Foo Fighters (example: the hilarious “Learn To Fly“). But everyone involved hated the results of the “Wasted Pretty” shoot, and the label pulled the plug on it almost immediately.

Maybe to take the financial sting away from the aborted video shoot, the label produced a second video on the cheap for a new lead single, “Favorite Shirt,” which had been written by Donnelly, shooting it in locations around Saratoga, including the band’s house at 36 Franklin Street and a friend’s bar, E. O’Dwyers on Spring Street (where Red Wolf is now located). Featured in the video were friends of the band, including Saratoga band Dryer‘s Bob Carlton, and Todd Strauss, the younger brother of soon-to-be-famous journalist Neil Strauss (of The Game fame), who at the time, was writing for The New York Times. Needless to say, the fact that the new single had been written by Donnelly, whereas the shelved one had been a Gent number, the focus shifted to the young bassist, raising his profile in the band. It didn’t lead to any conflicts between the friends and bandmates, but it did make for some friendly competition. Donnelly says it got even a bit more complicated than that in the years to come. “As soon as you get into the major labels, the contracts start coming in, and they have ‘key member clauses,’ which were that the band, The Figgs, only exists if Mike and I are in it; the other guys are expendable,” he explains. “It was really awkward amongst friends.” Donnelly also says he didn’t really feel like a lead singer type. “I don’t really know why ‘Favorite Shirt’ got picked as the first single,” he says. “Of course I was excited that it did for selfish reasons, because it was my song, but it’s kind of an odd song.” Donnelly says it even caused a bit of an existential crisis for him: “I remember being in the boardroom [at Imago] looking out on Central Park in this incredible office and thinking to myself, ‘God, I don’t belong here.'”

Despite the initial false start, “Favorite Shirt” proved to be a solid choice as Low-Fi‘s lead single. It not only found its way on the radio, but also MTV. A major portion of that radio strategy would be executed by Imago’s Northeast Regional Promotion Manager Jocelyn Taub, who handled the northeast, New England and Mid-Atlantic territories. “My job was to make sure the radio stations in my marketplace heard the music and ultimately played the record,” she says. “It’s hard to get any new band played, but at least with The Figgs, they were able to get some hometown support on stations like WEQX.” (I, for one, remember hearing it on the station.) In an August ’94 issue of Hitmakers magazine, it’s also noted that the band received early airplay from WFNX in Boston and WRLG in Philadelphia, two major-market stations. Radio-wise, Taub explains that the label had an advantage with The Figgs, because they already had a well-established following in the Capital Region and northeast. And well, it was also a plus that the guys in the band weren’t normal rocker types: “They didn’t have that get-me-the-brown-M&Ms-only [mentality],” notes Taub.

In regards to the “Favorite Shirt” video airing on MTV, that’s a bit of a different story. Says Donnelly: “When we were told that the video was going to premiere on MTV, we were so excited. We were on the road in Richmond, VA, and we went to the bar and asked if they’d put on MTV, because they were going to play our video. Iggy Pop was the host. He got up and he’s like, ‘This band’s been together for seven years already,’ and he had some really cool things to say about us, and then he fades away, and they play a Shudder To Think video. And we were sitting there with our mouths agape, like, ‘What?!’ It was such a letdown. It felt like this was indicative of how things were going to go. Nothing’s going to be smooth. After the next commercial break, [‘Favorite Shirt’] was the first song that played. We weren’t devastated, but it was a mixture of total embarrassment and excitement.”

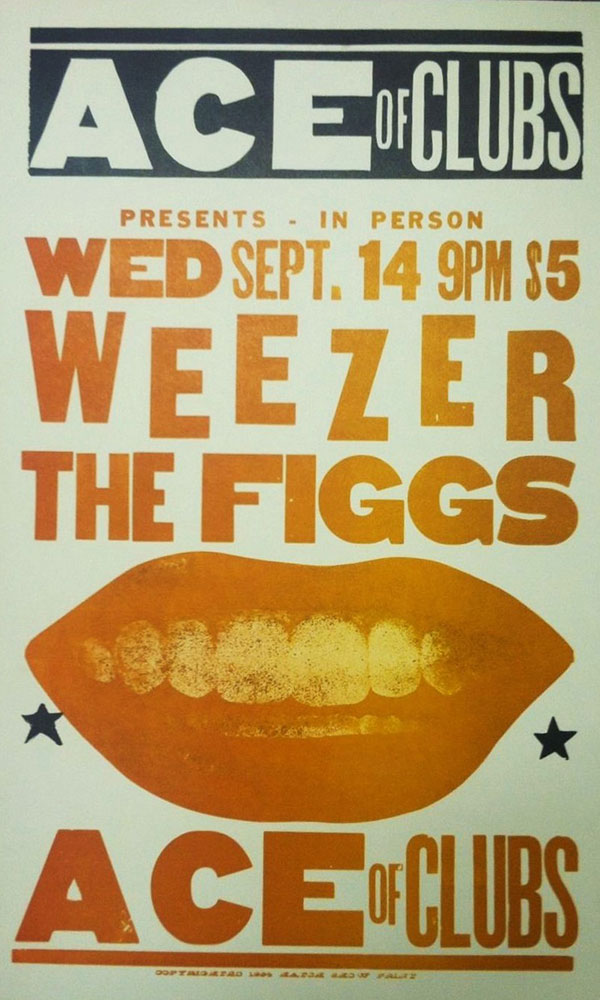

As Imago continued to roll out their Figgs world domination plans, the band found itself playing with a number of up-and-coming acts on a number of mini-tours peppered throughout 1994. Beginning their own official tour supporting Low-Fi at the aforementioned E. O’Dwyers in Saratoga, The Figgs opened for The Knack (of “My Sharona” fame), who had recently reunited, for which The Figgs were given a sizable and positive write-up in The Times by their buddy’s brother, Neil Strauss; shared a stage with soon-to-be top-of-the-charts Brit Rock band, Oasis; and did a turn with West Coast alt-rockers, Weezer, whose first single, “Undone – The Sweater Song,” was steadily climbing the charts. “The Oasis show was their first US show,” remembers Donnelly of the gig, which went down at the Metro in Chicago that October. “There was all this hubbub, and we were like, ‘Oasis, who?’ I remember there’s a great video of them being interviewed, and Pete Hayes sits down right with them, and one of the [Gallagher] brothers was like, ‘Who’s he?'” (Hayes confirms the story, saying the interview was taking place in Oasis’ dressing room and being done by a public access television company.) Of course, Oasis would go on to become one of the most successful rock bands in history. Donnelly also remembers playing with Weezer, and audiences being really mean to the band, because they only had one single on the radio at that point: “Undone – The Sweater Song.” “Some of those Weezer shows, the crowd would empty out after they played ‘The Sweater Song.’ Imagine that!” Hayes adds that Weezer was so green they really didn’t have a body of work to play besides tracks from that first album (The Blue Album)—whereas The Figgs had seven year’s worth of songs to choose from. (It’s worth noting that the band’s second single, “Buddy Holly,” went to No.2, and Weezer’s since scored a string of top 10 singles, including four chart-toppers.) And as Gent adds, the Weezer gigs were some of The Figgs’ best performances. “We went over really well; crowds really liked us,” he says. “It was shocking.” As far as interactions with the band are concerned, Donnelly says that the two bands didn’t have much in common and had a tough time connecting. Regardless, the quartet was having the time of their lives. “The Figgs were on fire that year,” says Donnelly. “We were eating it up.”

One moment from The Figgs’ tour had a particularly profound effect on Lyons. After playing a gig in Green Bay, Wisconsin—the last show of The Knack tour—a kid came up to him after a show and professed his love for Lyons’ guitar work. “All of a sudden I realized: This is what I would be like if I was meeting one of my favorite guitarists,” he says. “He was showing that admiration for me, and I was very flattered by that.” (Interestingly, the band has a major pocket of fans in the Midwest, specifically in Wisconsin.)

Of course, there was also a string of shows on the home front. As Donnelly notes, sometimes when a local band blows up and gets a record deal, fans reject them, because they feel as though the band has “sold out” or became snobby with fame. That never happened with fans in the Capital Region. “Though we reached this national status by getting a record deal and touring the country, coming home and playing shows always felt so good,” says Donnelly. “It felt like you had a crew of people that loved what you were doing and reestablished all the reasons why we did it.” Lyons remembers a particularly funny encounter in Albany that drives that point home: The Figgs’ tour truck—which doubled as the band’s sleeping quarters between gigs—was double-parked, and a policeman stopped his cruiser nearby to investigate. Upon reading the side of the truck, on which the band’s name was emblazoned, he said, “You’re OK,” and drove off.

A few weeks before the Low-Fi tour wrapped, The Figgs made their national TV debut on The Jon Stewart Show (he of future The Daily Show fame), which was sort of a proto-Late Night With Conan O’Brien in the fact that Stewart invited all manner of up-and-coming bands onto the show, regardless of genre. (He hosted everybody from Weezer and The Notorious B.I.G. to Green Day and Danzig.) On it, the band ripped through their singles “Favorite Shirt” and “Wasted Pretty,” the latter of which had finally been released as single No.2, with a re-shot video. Donnelly had taken a bus in from Rhode Island to play the gig, and was under the impression that the band would be playing “Wasted Pretty,” because the second single was out at that time. When he got to Stewart’s set, the label had dialed in and said they wanted the band to play “Favorite Shirt,” Donnelly’s song. “My heart was beating out of my chest,” he says. “I was really nervous because I hadn’t thought I was going to have to sing on TV. I knew that I was a pretty terrible singer at that point, and what got me through shows was just the energy of the shows and the spirit of that. But TV’s different.” (Despite his modesty, you can see for yourself that he nailed it.) “When I went home and watched [the performance], I wanted to die,” says Donnelly. “I hated it so much. Please never let me see this again.” Fans have since shared the video on YouTube, and it still has the same negative affect on him (he hates it). As the credits of the show ran, The Figgs revved up again with “Wasted Pretty,” which Donnelly thinks was a much better take.

But touring in a converted truck across the country that leaked when it rained, was a furnace in the summer and a refrigerator during the winter months took its toll. The label had literally built bunks inside the truck for them, so as not to have to foot the bill on hotel rooms for a green band. “What I remember most about touring was the suffering,” says Donnelly. “Trying to sleep in the truck in the summer in Mississippi was dreadful.” Sure, a decade later, the band were seasoned pros at the vagabond lifestyle of the touring musician—with a network of friends and family members to stay with at most tour stops—but in 1994, national and international touring was completely new to them, and they didn’t have those connections. When the band eventually got off of that first major tour, the last thing they wanted to do was spend more time together at 36 Franklin Street, so one at a time, each member began to move out—and leave Saratoga. Lyons moved down to Albany and would eventually end up in the Big Apple. Gent moved to NYC. Donnelly and Hayes were the longest Saratoga holdouts—but both eventually jumped ship, Donnelly to Rhode Island and Hayes to NYC.

If you’re hoping for a spicy VH1 Behind The Music episode, wrought with lurid confessions of sex, drugs and rock and roll that happened on The Figgs first big national tour, Donnelly’s quick to say that the band wasn’t really into that sort of thing. Most of the time, they had girlfriends (no famous names) and just acted like normal twenty-somethings. “We smoked plenty of weed, we drank plenty of booze, hit on plenty of girls, but compared to being in the band Slade in 1977, it’s total kid’s stuff,” he jokes. Hayes says he indulged in the rock star lifestyle a bit, but that it was difficult to go too crazy, because they had a road manager who kept them in line. That, and the fact that they were touring around in a converted box truck didn’t make for much space to party or hook up. Gent concurs. “We didn’t do a lot of the traditional ‘band just gets signed and gets on a bus,'” he says, meaning that The Figgs didn’t blow money on a traditional tour bus and weren’t spendthrifts. The most extravagant purchase they made while at Imago was new gear. The rest of the time, they scrimped and saved and rode it out the hard way. And it turned out to be a really, really smart move.

Shortly after the band released their second single, “Wasted Pretty”—and about halfway through recording the follow-up to Low-Fi—Imago Records went belly up. The label had spent millions of dollars and had nothing to show for it in their bank accounts, so parent company BMG cut ties. “I wish I could’ve continued a bit more on that label, because we did feel really supported and welcomed there,” says Gent. “A lot of the staff at the label really liked the band and were really excited about us.” (Both Aberle and Taub spoke very fondly of the band during our interviews.) Donnelly remembers thinking, well, that means that the band would get the rights back to Low-Fi. That wouldn’t be the case. In fact, 25 years later, the band still doesn’t own the rights to the record. “It’s one of the greatest crimes of the music industry,” says Donnelly. “A record company can own your product [even though it’s] nonexistent.” That said, Gent believes that being signed by Imago was a major step in the band’s history and one that probably kept it going for all these years. “If we had never been signed and just went about our business, trying to make records independently, it would be interesting to see what would’ve happened [to The Figgs],” says Gent.

Despite Imago’s untimely demise, it didn’t ring a death knell for the band. They were quickly re-signed, this time, to a major label, Capitol Records, who unlike Imago, had scads of other artists on their roster and to that end, paid little attention to the band. The band-label marriage was anything but amicable and would be a short one; after just two years, one album (1996’s Banda Macho, the album they’d begun recording with Imago) and some heavy touring, The Figgs were unceremoniously dropped. “Our relationship was so ugly, right from the start, it’s a miracle that they signed us and didn’t just tell us to piss off,” says Donnelly. “And they gave us a good deal.” He realizes now that, though the record they made was good, in hindsight, there was nothing commercial about it at all. “To have complete, self-indulgent freedom as a band on Capitol Records is kind of a miracle,” says Donnelly. “[Lo-Fi] didn’t prepare us in any way to know how to function in the big leagues. I think the opposite happened: We broke down and became a lot more self-interested, in a way, and dug our heels [in], to say, like, ‘We’re in control of what we’re doing.’ And the industry was like, ‘Well, bite me, then.'” Despite the band-label tension, The Figgs were able to tour with more buzzing acts, such as Supergrass, Jimmy Eat World, Letters To Cleo and scored a spot on the Warped Tour. “A lot of people expected us to stop and break up after the two years on Capitol, because that’s what happens,” says Gent. They, of course, did just the opposite. And Gent offers up some wisdom for newer bands out there that are looking to make it. “Whether we had a record deal or nothing, we never spent our own personal money on the band,” he says. “It’s always been money that we’ve made [as a band]. And that, to me, is 100 percent, complete success.”

***

On the 20th anniversary of Low-Fi At Society High in 2014, the original quartet—Mike Gent, Pete Donnelly, Pete Hayes and Guy Lyons—reunited to play a string of dates. I caught two of the shows—one at the Bowery Electric in New York City’s Lower East Side, the other at Putnam Den in Saratoga (now Putnam Place). The band played the entire, 15-song album, front to back, and it was like reliving a part of my youth. Sure, I was in my 30s and the players were in their 40s—and it was tougher to evoke that youthful energy they had on, say, The Jon Stewart Show—but you could tell the band members were having fun with it. “The energy felt so good and focused,” says Donnelly of the shows. “I was really glad we did that.” And it was nice having their friend, Guy, back in the fold; there was never any animosity, says Donnelly, who still calls him a “dear friend.” (At the time, Lyons had launched his own band, Blockhouses, which opened up for a string of the Figgs’ reunion shows; the band released their full-length debut in 2018, Greatest Hit Songs of All Time, which was produced by Donnelly, only to amicably break up earlier this year.) Adds Gent: “Some of that stuff we hadn’t really touched since Guy left.” Lyons tells me he had to relearn a number of the songs from Low-Fi to play that string of shows. “I’m not as good a guitar player now as I was back then,” he says. “I listen to some of the guitar playing that I did on Low-Fi…and I’m just like, ‘Holy shit, I can’t believe I can play that.’ Because when I left the band, I didn’t really play guitar for 15 years.” While it was a little bit harder to actually play the tunes—after all, some were a bit faster than the mid-tempo numbers the band tends to write nowadays—it was a real eye-opening experience. “It reignited a feeling [in me] that that record was special,” says Donnelly. “It was the world’s—[Laughs] small world’s—initiation to what The Figgs are.”

It’s a rarity when a band stays together as long as The Figgs have—30-plus years!—and that fact is not lost on its members. Gent chalks that staying power up to the seven years The Figgs were a touring band before they ever got signed to a label. Despite Lyons officially leaving The Figgs again in 1998, this time for good and right before the release of the band’s independently released album, The Figgs Couldn’t Get High—Lyons settled in Harlem and has worked a “normal” job for Verizon for more than 16 years—the band has soldiered on and toured extensively as a trio. They’ve acted as the backing band for ’70s rocker Graham Parker, whom they’ve also recorded with, and The Replacements’ Tommy Stinson; and put out an impressive body of work, including several EPs, a number of live albums, reissues, a double-album in 2004 (Palais), a personal favorite of mine in 2006 (Follow Jean Through The Sea) and two albums in two years between 2015-16 (Other Planes Of Here, On The Slide). “They moved on as a band and evolved into something that was really different from what the band was like when I was in it,” says Lyons, now speaking from the perspective of a fan. He’s right; they’ve never sounded better—and a lot of that has to do with the gamble Imago took on that little band from Saratoga, and the wonderful album, Low-Fi At Society High, which will forever be a part of my record collection.

Song-By-Song Analysis: Low-Fi At Society High

For Figgs superfans, this section might be old hat; it’s possible that you’ve heard these stories in some way, shape or form throughout the years recounted in magazine articles or online interviews or after gigs, chatting with the band. (Heck, maybe you’re even related to one of the band members and lived these stories in real time!) But for you Figgs newbies, this will give you a secret hallway pass into the lives of the members of the band and how they went about writing the songs that wound up on Low-Fi At Society High. As Gent notes, “I think [all the songs] were written in Saratoga,” so there’s a local tie-in to the album, regardless of whether there are actual hat-tips to spots in and around the Spa City.

As I mentioned above, the majority of Low-Fi‘s songs, with the exception of a handful, were already in the band’s back catalog or set lists, so it wasn’t that big of a stretch to re-record them one more time—especially with the bigger budget Imago had to offer the band. But that didn’t make it any less nerve-wracking for Hayes, who had to play to a click for the first time in his life (i.e. an electronic metronome that keeps you on the beat while you’re putting a song to tape). One noticeable difference, sonically, was the fact that Lyons was now in the band, contributing frenetic guitar solos and the new riffage he’d been writing. “I play most of the guitar solos on Low-Fi,” he tells me, with the exception of “Chevy Nova,” which is all Gent. As Lyons puts it: “When you’re listening to [Low-Fi] with headphones [on], all of my guitar playing is in the right ear [and in the left, Gent].”

“Step Back, Let’s Go Pop”

Gent: “I wrote this one, ‘Cherry Blow Pop’ and ‘Stood Up!’ on the same beautiful, sunny spring day on a hill in Congress Park in Downtown Saratoga. I brought an acoustic [guitar] and a notebook with me and later walked home with all three songs finished. All of them heavily influenced by the [Elvis Costello] record Get Happy!!. The line ‘The leaves are turning green’ has always bugged me. It should be ‘The trees are turning green[.]’ I was very satisfied with the riff at the end of this one, though.” [Editor’s Note: In an earlier interview with Gent, he also mentioned that The Beach Boys’ album, Friends, influenced the trio of songs as well.]

“Favorite Shirt” (first single)

Gent: “I have a pretty clear memory of learning this in the Donnelly’s basement right before Guy rejoined the band in the fall of 1992 [and] playing it over and over. It felt special right away. It was the first song of ours that many people ever heard, even though we had already been a band at that point for seven years. I like the version on Ready Steady Stoned, too. It was an obvious choice for a single, and we still mess up the intro.”

Lyons: “I created the guitar solo in the middle part of ‘Favorite Shirt’; I think I just made it up on the spot.”

Jocelyn Taub, former Northeast Regional Promotion Manager, Imago Records: “When we started promoting ‘Favorite Shirt,’ we made up these bowling shirts with the radio people’s names on the pocket.”

“Wasted Pretty” (second single)

Donnelly: “The lyrical elements to the song often don’t make sense out of the music. I feel strongly that if you write the lyrics down, they won’t make sense. Lyrics are images that fit within the sonic pallet, and yes, they might tell a story. We were comfortable with that stream-of-consciousness. We weren’t really good at being the folk song types. The lyrics were not necessarily rewritten or thought about [much]; they’re immediate, impulsive. They may be a jumble of thoughts about things. At least in my own songs at the time, they shift tense all the time, and shift in perspective, depending on which line. My thought about that was always: It doesn’t matter what it’s about; it matters only to the listener, because they don’t have us to explain it. It’s kind of like going to a museum and looking at a painting and not reading the description, which often I don’t want to do. I’m into art history and music criticism to an unlimited degree, but I also just want the immediacy, and I feel like a lot of the songwriting of the band, particularly of the time, was just stream-of-consciousness, impressionist, impulsive.

“Mike’s really clever and catchy with the way he likes to flip words. People forever called the song ‘Pretty Wasted.’ Maybe it’s playing on that age-old adage that when you’re drunk, you’re prettier. When you’re a teenage boy—and we’ve been criticized for this—almost all of our stuff [from that era] is about relationships with the girls in our lives, to some degree.”

Gent: “There are songs that I can remember where I was when I wrote them, and others, where I have zero memory of where or when they were written. This falls in the latter category. I do remember that I was still in my teens and still living with my parents and siblings when I wrote it, and who it’s about. Pete [Donnelly] sometimes requests that we play this one, and I usually feel indifferent. We played it a lot back then, and I know a lot of fans like it. It was originally planned as the first single from the album, but it was switched to the second single, which was a good decision, although there are other songs on the record that would’ve possibly brought us more attention. There’s an unfinished, unreleased video that Imago spent a ton of money on. I wish we had that money now; we could make at least five records with it!”

“Bus”

Donnelly: “I think when we got in the studio, the A&R guy [Matt Aberle] wanted [us to record] ‘Bus,’ [but] he didn’t like the recording; it was too slow. This is, maybe, the beginning of antagonism between the band and [music] industry, because in hindsight, it seems so obvious to me: [If] you’re doing business with somebody, you should consider their opinions on the product they’re going to be working [on]. But at the time, we were encouraged by our management and even our producer to disregard the opinions of the industry. So we sped up the song a little bit. I think in the end, the recording is pretty good, but I think he didn’t want it to be a single.”

Lyons: “On ‘Bus,’ all the wah-wah stuff is [me].”

Hayes: “I always had a problem with ‘Bus.’ I always felt self-conscious about the beginning of the drums on that [one].”

Gent: “Not sure what I was trying to accomplish with this one, lyrically. [Quotes lyric] ‘Stranded down in Harlem?’ Upstate perspective, I guess. It’s always fun to play. It was written in my first apartment on the corner of Broadway and Caroline St. [in Saratoga Springs]. I wrote most of my songs on Ready Steady Stoned, Low-Fi and tons of others in this apartment. I had a big bedroom with high ceilings. My window looked out onto Caroline St., so it was very loud at night. Sometimes, I’d wake up around 3am, and it would sound like Mardi Gras out there! Lots of songwriting, making demos and listening to records happened in that apartment. A magical time in my life that I attempted to capture and explain in a song called ‘Taking A Grass Bath.’ I believe ‘Bus’ got a lot of airplay in the Capital Region at the time, because people would request this one a lot in Albany. There’s a better version that we recorded for Columbia in 1993 that’s never been released.”

“Slowdown”

Donnelly: “If you’re writing a song, it isn’t necessarily about how you feel about the world; you might just be describing something. A lot of what we see is fucked up or twisted, and we see all kinds of screwed up behavior between people, and a lot of times, we’re writing songs describing that and the reactions to it. It may not necessarily be endorsing that behavior. In the song ‘Slowdown,’ it definitely was one of those things where maybe it seems reckless for someone at that age to use some of that language, but it was an attack on poseurs. I’ve never really considered what the song is about, but when you’re becoming an adolescent, you fear everything. Social fear, fear of rejection, and when you see the ways people behave, it seems so shallow. I think it was a way of commenting on how shallow the hookup scene is and how I didn’t want to take it seriously.

“Musically, it’s one of the coolest things I had done. It started as a piano piece, and so did ‘Jump Start.’ Both of those were piano compositions, initially. I was really into piano and Stravinsky and Beethoven at the time. I’d always done that; I’d always looked way outside of the immediate influences for musical inspiration.”

Gent: “This is always fun to play. It falls into this prog thing we were doing a bit on Ready Steady Stoned (“Your Control,” “Half Jerk,” “Formaldehyde” [Editor’s Note: The latter two are outtakes only available on the album’s Deluxe Edition.]). I remember this was in the newer batch of songs we had when we recorded Low-Fi, so I was more excited, at the time, with this than some of the older material that the label wanted us to re-record. I always had mixed feelings about the lyrics on this one. I loved some of them, but others not so much. I really wished [Pete and I] were more open to helping each other out [by spending] more time [to make] our lyrics better, because we both could use each other’s help, especially back then. I’ve always struggled, and still do, with lyrics, [but] Pete was [too] close to his to take any suggestions or opinions. Guy probably wrote the strongest lyrics at that point (’80s and ’90s).”

[Editor’s Note: I’d be remiss not to mention what the band is referring to with the lyrical content of this song, some of which likely led music critic Ann Powers, at the time writing for Spin magazine, to round up her otherwise favorable review of Low-Fi At Society High with a rather serious caveat. (My question about its controversial lyrics prompted the above response from Donnelly.) Powers wrote: “Singer-guitarist Mike Gent and Pete Donnelly nail the snotty attitude needed to pull off their paeans to boy frustration. Leavening their considerable cuteness with an artful sneer, the Figgs achieve nerd-punk pinup status. My one complaint: It’s just not cool these days to scorn women, boys. You only do it sometimes, but continue and some girl’s gonna corner you and kick your collective ass.”]“Chevy Nova”

Gent: “This one, as well as [Ready Steady Stoned‘s] ‘New Car, No Rent’ were written on the same day in my living room at the Broadway apartment [in Saratoga]. Our road manager, Kevin [Ure], had owned a beat up Chevy Nova that we were riding around in one winter evening. He hit a patch of ice, we did a 180 and hit a telephone poll. It scared the shit out of us! This was one of the songs that we recorded many times before Low-Fi, so by the time we got to this version, I was over it, I guess. Always a fan favorite.”

“Ginger”

Donnelly: “It’s probably the most direct and emotionally pure song of mine on there. The song is titled after the record [Ginger]. ‘Ginger’ is one of those things that has multiple meanings, and [The Figgs] liked that kind of thing. It’s an emotion, it’s a physical feeling: ginger, gingerly, a ginger touch. Or to tread delicately. It was also a girl’s name, [and] obviously, we were fixated [on] girls. I think Mike named it, and it just made sense.”

Gent: “Another fan favorite. People still yell out for this one. It’s too bad Imago didn’t release this as a single. It’s a strong song that we were proud of at that time. We recorded it for a record that never came out in 1993. [Editor’s Note: It was the lead track on the unreleased Waiting for the Bugasaurus.] That version was probably more interesting, psychedelic and sloppy. We really worked hard tightening up our arrangements and performances for Low-Fi, which some people enjoyed and others wondered where the slop went. I was in the middle. I enjoyed being in our first professional studio with a professional producer.”

“Shut”

Gent: “Another one [that was] written in the bedroom of my first apartment [in Saratoga]. I don’t remember who it was about—maybe I’m singing to myself? I always enjoyed playing this one, because at the time, it gave us a break and some breathing room from the nonstop bashing we were attempting. You know, some space…we didn’t have many songs like this at the time.”

“Cherry Blow Pop”

Hayes: “We recorded that really quick, and I felt like a champ.”

Gent: “This was a song originally called ‘I Kick The Wall,’ which was probably a better title. It had some different sections that I replaced. I banged it into shape in Congress Park [see: ‘Step Back, Let’s Go Pop’]. [It’s] about a girl that I was close with. Listening to the lyrics, it seems that something about our friendship was frustrating me. A lot of our early material was just complaining about the inability to cope with relationships and the normal troubles of boys in their teens and early 20s. Not having the correct emotional tools, etc. So many tiny issues/problems seemed like the end of the world to me at the time, and I would write about it. This is sometimes why I have a hard time revisiting some of this earlier material. I was so much younger then, I’m older than that now.”

“Jump Start”

Gent: I love this one. I remember having the feeling that we stepped into a different level after we learned this song. I love the Ready Steady Stoned version. There was also a moment when Pete [Donnelly] added the keys on that first version where I thought we were really onto something special. Pete has always been a bit down on the lyrics, so we don’t play it enough. I think they are great and very poetic. Always loved singing it with him, especially when we both sing the verse together in unison, [because it’s] a live double-track effect (something we should do more often). It really showcased our ability to harmonize, which was out of the picture for most bands in the early 90s. Also, Guy and I are playing two very interesting guitar parts throughout. This one needs the two guitars live, another reason why it probably doesn’t show up anymore in the sets. Whenever I hear this song, it has the ability to bring me right back to the early 90s and great memories.”

Lyons: “[The opening] lick…I played all of that stuff.”

[See entry on “Slow Down” for more from Donnelly on the song.]“Stood Up”

Gent: “Trying to do my best Elvis Costello [see: ‘Step Back, Let’s Go Pop’]. Again, this one was recorded many times before the Low-Fi version. I forget which one was the best.”

“Asphalt”

Gent: “We played this a lot in the 90s. Once Guy left, it was really never played again, maybe once or twice. I think Pete [Donnelly] wasn’t feeling it anymore. We toured Low-Fi for seven months straight and played most of these songs for many, many years before, as well as long after the record came out. I’m still burned out on a lot of the songs from this period, even though we really haven’t touched some of them for a very long time. I think it’s healthy to put certain material away for awhile, so maybe down the road, you can dig it out and really see if it’s a good song that still holds up. I wish we did this more often with some of the older stuff. This has a decent guitar solo by moi. We had a lot of new material going into these sessions for Low-Fi, and this was a newer one at the time. I recently listened to two rehearsal tapes from January 1994—right before we went into the studio—and there’s a handful of songs we were working on that were dropped by the time we started recording. Completely dropped…never revisited or played live.”

“Waltz for Bob”

Hayes: “It was real tricky [to play] because it was a waltz. I remember writing that song…I helped Pete [Donnelly] write that song, but not enough, I felt, that I deserved a credit. I remember after we toured with the Cranberries, those guys had all these waltzes, and we were like maybe we should play a waltz, too. I remember coming up with a couple dumb lyrics for it.

“I remember specifically playing the high-hat on that song, and I was trying to make every high-hat hit be unique and have its own soul. I remember being very aware of what I was playing. The idea for it [came from] Percy Sledge’s ‘When A Man Loves A Woman.’ I liked what [the song] was about, because Bob was a very special cat to all of us. There’s a picture of that cat in [the liner notes to] Low-Fi. It was our friend Amy’s cat, who kind of just ended up with me at [my apartment in the] Algonquin [in Saratoga].”

Gent: “This was a newer song that we worked on for a long time at the Franklin St. house [in Saratoga], where we all lived at the time of being signed [to Imago Records] and recording Low-Fi. It was new territory for us: a waltz! A song about the band’s cat, Bob. She was a special kitty. There’s a picture of her in the [album] artwork. Another song written and rehearsed at the same time, but not recorded at the time was simply called “Cat.” Both songs are great. [Editor’s Note: The latter appears on The Figgs Couldn’t Get High and was written by Donnelly.]

“Charlotte Pipe”

Gent: “Another brand-new song at the time that was written, learned and rehearsed at the Franklin St. [house] right before we went into the studio [to record Low-Fi]. In fact, I believe it was the first song we cut at Dreamland for the LP. I bought a DAT [Digital Audio Tape] deck right before the sessions started and brought it with us into the studio. It was a very big expensive purchase at the time. I also bought three cases of blank DAT tapes and recorded almost the entire sessions for the record. I remember bringing it back to the house where the band was staying while we were making the record, so I could listen to the day’s session and make notes. ‘Charlotte Pipe’ was, for some reason, buried at the end of the record, which was too bad, because I thought it was one of my stronger songs at the time, with interesting chords and lyrics. I love the piano I put on this one, and Guy’s playing was also essential to the arrangement and very creative. Listening to this track always brings me right back to those sessions more than anything else on the album.”

Gent (on what a “charlotte pipe” is): “‘Charlotte Pipe’ was just something that I saw—it’s a brand of plumbing pipe, I think. I saw it in a bathroom when I was taking a leak. It had nothing to do with the song, but I thought it was a good title.”

Hayes: “‘Charlotte Pipe’ was really, really difficult for me [to record], because it had these weird syncopated accents that I had the hardest time playing. I kept rushing them. It probably took me a whole day to record that. At times, though, it’s been my favorite song on the record.”

“Tint”

Gent: “The only reason I can think of [for] why this was included on the record was, again, [that] it was brand new at the time, and we were determined to fit new material on the record along with the older material that the label wanted. It’s a terrible song that means nothing. My vocal performance is awful, and I remember struggling and rewriting the words, overthinking [them]. We never played it much, because it’s a stinker. I don’t think anyone in the band liked it. Again, we had stronger material, so it’s a mystery how this even made it onto the list of songs to record. Maybe [Low-Fi‘s Producer] Don [Gehman] liked it? It could have been that I was into it for a second and pushed for us to do it? The only person I’ve ever heard yell this out as a request is Rev Norb. Maybe he’s just screwing with us! How this made it onto the LP and ‘Lynette’ was left off is a mystery and a crime. Huge mistake leaving ‘Lynette’ off. We also could have just left ‘Tint’ off and made it a 14-song LP. I’ve written way worse [songs], but this one is on my shitty-songs-I-have-written list. Oh well.”

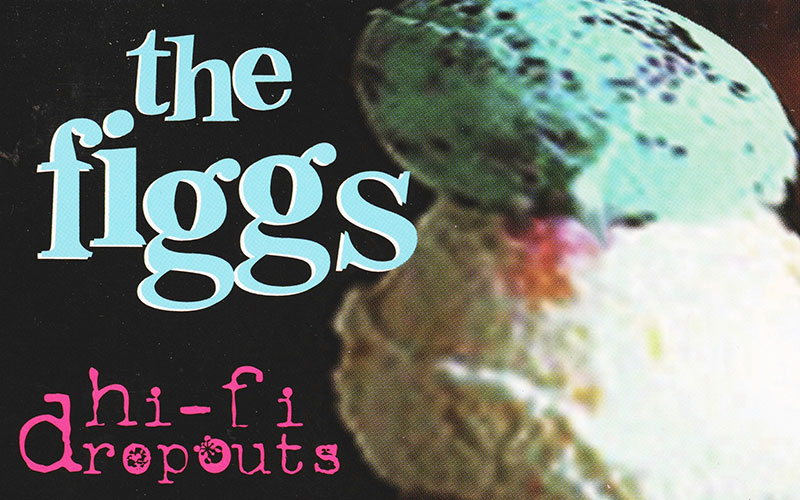

Odds and Sods: Hi-Fi Dropouts And More*

Odds and Sods: Hi-Fi Dropouts And More*

“Lynette”

The song dates back to the Ready Steady Stoned session and is attributed to both Hayes and Donnelly. (Interestingly, it would be Hayes’ only contribution, song-wise, until 1998’s The Figgs Couldn’t Get High, though his songwriting kicked into high gear from 1996-97.)

Hayes: “I wrote that song. Pete [Donnelly] got half of a credit, because I don’t play guitar for shit. I’m pretty generous with my credits. I sang my idea for the song, he was playing chords, and we worked it out together.”

“Punch”

Donnelly: “I think ‘Punch’ is from a Columbia [Records] demo.”

“Village Green” (Kinks cover)

Donnelly: “Mike always loved The Kinks, and he just had those songs. There certainly wouldn’t have been any talk about why we chose it. I think we just started cutting it.”

“Jupiter Row” (on 2012’s The Day Gravity Stopped) – Gent notes that there’s a line in the song that refers to the Low-Fi era: “Many moons surround us, as you can see/All of a sudden they found us in 1993.”

*Hi-Fi Dropouts was released in August 1994 as an EP, featuring the single version of “Favorite Shirt,” an alternate take of “Chevy Nova,” a cover of The Kinks’ “Village Green” and a pair of alternate versions of songs that first appeared on Ready Steady Stoned, “Lynette” and “Punch.”

5 Bands To Watch

So now that you’re up to speed on The Figgs, here are five local bands and artists are keeping the rock torch burning bright in the Spa City.

Dryer (Saratoga Springs) Contemporaries of The Figgs, Dryer has been rocking hard since 1992. Did I mention that bassist/vocalist/songwriter Rachael (Rieck) Sunday is saratoga living’s longtime Subscriptions Manager? I can subscribe to that.

The Sea The Sea (Troy) This husband-and-wife duo is, in my book, the Capital Region’s next Phantogram. Their 2018 album, From The Light, puts their harmony-heavy, anthemic indie rock on full display. They’re like a hipster pool party hosted by The Civil Wars and Coldplay.

Girl Blue (Troy) Arielle O’Keefe (a.k.a. Girl Blue) once starred on E! reality show, Opening Act, where she got to open for music legend Rod Stewart. Since then, her bluesy electro-pop has helped her rack up millions of streams on Spotify. She’s got “it.”

Candy Ambulance (Saratoga Springs) This grunge-rock trio is led by guitarist/vocalist Caitlin Barker, who might just be the lovechild of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ Karen O and Hole’s Courtney Love. Prepare to bid your sonic innocence adieu. (Note: The above video is NSFW.)

Belle-Skinner (Troy) Belle-Skinner (or to her friends, Maria Brosgol) is, at her finest, just a one-woman show—an electric guitar drenched in reverb accompanied by her impossibly angelic voice. Hey, Sufjan Stevens: The next time you head out on tour, make Belle-Skinner your opener. (Check out Belle-Skinner’s cover of Stevens’ “John Wayne Gacy, Jr.” above.)