This is the story of how Saratoga Springs became the city you know and love today. Don’t stress—this isn’t a dense-as-Uncommon-Grounds-on-a-Saturday-morning history lesson. Expect instead more of a trip down memory lane with none other than Spa City founding father Gideon Putnam himself, who arrived in Saratoga Springs, saw its potential and kickstarted a 200-plus-year quest to design a community, then township, then city, that would live up to the bountiful natural resources it had been blessed with.

Delving into why Saratoga looks the way it does yields almost an embarrassment of riches to explore, from Putnam deciding his new home should have a “broad street” as its defining feature, to the city’s current-day design review process. Saratoga is more than a collection of buildings, streets and trees that have popped up at random since 1789; it’s actually a dynamic, ever-changing chessboard in which architects, business owners, homeowners, government committees and nonprofit organizations all work together to preserve the character of the city, while ensuring it remains an attractive place to settle for future generations. Says Tamie Ehinger, the current chair of the Design Review Board (DRB), one of Saratoga’s aesthetic gatekeepers: “If we were to ever lose the magic that makes this Saratoga, it would be a travesty.”

Thankfully, the City of Saratoga has indeed retained its magic and become nothing short of a design masterpiece.

Harkening back to any town’s early days is, of course, going to require at least a little bit of a history overview. All Saratogians (we hope) know that the first Spa City settlements were formed around its mineral springs, High Rock Spring being the first. In the mid-to-late 1770s, this important spring about a mile north of what is now Congress Park was home to a small settlement that came to be known as the “Upper Village.” When Putnam arrived, he was dazzled by Saratoga’s natural resources, famously telling his wife: “This is a healthy place, the mineral waters are valuable, and the timber is good and in great abundance.” He began developing a “Lower Village” near Congress Spring, and the excitement began. In addition to building his tavern and boarding house (which would eventually become the Grand Union Hotel) in this new Lower Village, Putnam “laid out streets, donated land for a cemetery and offered land for a church building…in the growing community,” Jan Johnstone writes in her book Saratoga County Communities: An Historic Perspective. “He built a second hotel, Congress Hall, opposite his tavern, to house patrons of the springs.”

Eventually, in 1819, Saratoga became a township and construction ensued, including the building of the massive United States Hotel. Shortly after, the Saratoga and Schenectady Railroad was constructed, giving tourists easy access to the Spa City and making it a destination for political, professional and religious conventions. And what does a city with a sudden influx of tourists and convention-goers need? Even more hotel rooms.

This design-by-necessity characterized much of the development of Saratoga throughout the 19th century, from the post–Civil War boom that resulted in the construction of a town hall, firehouse and schools, as well as the improvement of the city’s sewer and water systems and the building of more homes to accommodate its ever-increasing population. The city’s great hotels—Congress Hall, the Columbian and the like—were part of that growth and bridged the gap between “need” and the architectural and design brilliance for which the Spa City has become known for today. Because we certainly don’t live in a town built solely on need. Saratoga Race Course and the expansive, extravagant mansions that line North Broadway and Union Avenue didn’t necessarily need to be that expansive or extravagant. Regardless of practicality (or lack thereof), it’s these grand Victorians and the Thoroughbred track that defined the design of Saratoga in the 1800s—and that still does to this day.

Fast forward to the turn of the century, past the fires that destroyed hotel after hotel, the rebuilding of said hotels and the wealthy summer tourists who ventured to Saratoga for its racetrack, casinos and healing springs. Let’s also skip over the crackdown on gambling and its economic impact on the city’s hotels, the founding of Skidmore College and the opening of Yaddo, plus World War I, and the Great Depression’s disastrous effect on businesses and homeownership. And finally, let’s fly past the creation of the Saratoga Spa as part of the New Deal, World War II (the final straw for the remaining grand hotels), and another wave of fires that left Saratoga the roll-a-ball-down-Broadway-and-hit-nobody wasteland that Marylou Whitney found when she arrived here in the late 1950s.

That brings us to the midpoint of the 20th century, which some Saratogians of a certain age might still remember. This is when the development of the city we see today kicked into high gear, thanks to new government programs, involvement of the private sector and volunteer efforts.

Since the mid-1900s, Saratoga’s layout, skyline and overall design aesthetic have been dictated by several key boards, organizations and initiatives, which have done a lot of the important work that has kept Saratoga Saratoga. Per the City of Saratoga Springs’ 2015 Comprehensive Plan, “The power of place is critical to the character and economic longevity of a community.” Additionally, the plan states that “enhancing and preserving that sense of place, while also embracing the changes necessary to compete with today’s ever changing world requires a careful balance.”

Saratoga’s Zoning Board was established in 1937, and in the late 1940s, the then-new Saratoga Planning Board commissioned a citywide survey to determine what residents wanted. This marked one of the earliest recorded governmental efforts to take an active role in the future design of the city. Since then, the government has prepared similar reports every few years, all the way up to present day; Mayor Meg Kelly is currently heading up the creation of a document known as the Unified Development Ordinance (UDO). “We’re going to include the urban forestry, the complete streets and the Greenbelt trail,” Kelly says. “It’s getting all of those, if you want to call them subcommittees, into one user-friendly document, unlike what it is now. Hopefully, we’ll be voting on that by the end of the year.”

After that 1940s survey—which, by the way, recognized the need for more parking and an arterial highway for through traffic (sound familiar?)—the next major step in the development of Saratoga was the national Housing Act of 1954, which introduced the concept of urban renewal to many cities across the country. In theory, urban renewal was supposed to spruce up areas of the city that had fallen into disrepair. In Saratoga, as in other urban areas, it did that, while also demolishing historically black neighborhoods and causing rents, mortgages and taxes to skyrocket. One positive byproduct, though, was the creation of a grassroots movement that supported the preservation and restoration of Saratoga’s historic buildings, the antithesis of urban renewal’s raze-and-rebuild mentality. “The historic districts in our city are part of the fabric of this community,” says Ehinger. “It’s part of what makes Saratoga special.”

By the ’70s, the Saratoga Chamber of Commerce’s “Plan of Action” had kicked off a community effort to revitalize the city’s downtown. The plan succeeded, and thanks to aid from the private sector and general public, 250 trees were planted, parking facilities and a convention center were constructed, and storefront vacancies quickly became a thing of the past. That decade, the preservation movement also metastasized into the Saratoga Springs Preservation Foundation (SSPF), an organization that has worked in an advisory role to the city’s Design Review Board (DRB) on all exterior changes to Saratoga’s historic or architectural districts, which span the city’s many entry points, as well as large swaths of downtown, Union Avenue and North Broadway, plus the neighborhoods surrounding

the racetrack.

What does it mean to have a business or home in either Saratoga’s historic or architectural review district today? Essentially, that you don’t have free reign over what you can do to the exterior of your storefront or home. “When you’re in a historic district, there’s going to be much greater scrutiny of the context of a new building, and any history of the site or building that you’re touching, particularly if it’s an existing building,” says Michael Phinney, owner and principal architect of Phinney Design Group, which has been designing homes and buildings in Saratoga for more than 20 years. Rather, you must apply to make said changes and follow strict rules and guidelines (Ehinger admits that the process “is not a cakewalk”) set forth by the DRB—by way of the US Secretary of the Interior—before being approved to do so. It’s a process that has certainly worked for decades but hasn’t come without its critics: The DRB doesn’t always side with businesses or homeowners on the changes they want to make, and applications can be rejected. That said, Phinney could only think of one project, in all the years he’d been working in the city, that “couldn’t get over the hump.”

However strict and unpopular the process may be, especially, perhaps, during the pandemic, when small business owners were trying to make any small improvement to give their businesses a boost, Saratoga’s design review apparatus isn’t unique. “Almost every major city that has historic architecture that plays a part in the fabric of the city has a design review board like this one,” says Ehinger. In fact, she and the other powers-that-be say Saratoga’s rules aren’t nearly as strict as other famous historic towns such as Savannah, GA; Alexandria, VA; and closer-to-home historic hot spots Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard. All have design review boards that dictate what people can and can’t do to their historic properties. At least here in Saratoga, the board rules on everything from business’ logo fonts and awning shapes, among other design elements. The reasoning behind all the rules? An owner of a historic property is considered not just its owner, but also its “steward,” says Ehinger. A historic building has had previous owners, and will have more owners in the future, and the only way to ensure that its historic integrity is preserved for years to come is through regulation. No matter how much of a headache it causes.

So there you have it: the design of the City of Saratoga in a not-too-tough-to-crack nutshell. (Okay, it’s an abridged version.) We didn’t get to mention the crowdfunding campaign that built the Holiday Inn, the creation of the Northway that made Saratoga just a three-hour (incredibly boring) drive from Manhattan, or the idea, stolen from Stowe, VT, to create a northern residence for the New York City Ballet (i.e. the Saratoga Performing Arts Center). We didn’t get to the city’s zoning regulations; the creation of the Saratoga Economic Development Corporation, which brought industry, and therefore large manufacturing plants, to the city; or the current issues surrounding affordable housing being stamped out by luxury condo developers. And we barely mentioned Marylou Whitney, the “Queen of Saratoga,” whose contribution to the revitalization of Saratoga in the second half of the 20th century cannot be overstated.

All these developments and more have made Saratoga what it is today—a city that Gideon Putnam, were he still around, would be proud to call home.

The Timeless Classic

Save for Fenway Park in Boston, Saratoga Race Course is just about as classic a sporting venue as you can find in the northeast. How has its charm been so carefully preserved? Location, location, location: Its of-a-different-era architectural style is owed greatly to its position inside a historic district protected by Saratoga Springs’ strict design review process.

Opened amidst the Civil War in 1864, the track didn’t get its much-needed aesthetic shot in the arm until after founder John Morrissey died in 1878. William Collins Whitney took over and hired renowned architect Charles W. Leavitt, who’s to thank for the track’s late-Victorian style that has remained consistent throughout its modern history, despite a number of upgrades and additions. One of the most notable was the construction of the three-story, luxury 1863 Club, which opened in 2019 and features materials like copper and slate on its roof, to echo those of the original Grandstand and Clubhouse.

Though the track was closed to spectators in 2020, a limited number will be able to return to the stands this summer. And that begs some design-related questions: Will fans be able to sit, socially distanced, in the historic Grandstand? Or stand, six feet apart, along the rail to watch the horses fly by? Or will it be a much more controlled environment? The lucky fans that do get through the turnstiles will be able to marvel at the track’s incomparable design once again—and maybe win a few bucks in the process, too. —Brien Bouyea

Bridging the ‘Old’ and ‘New’

If you were one of the lucky young women who attended Skidmore College in the 1960s (it went co-ed in ’71), you wouldn’t have been able to tell the campus apart from the City of Saratoga Springs’ East Side, because the two were one and the same. Disparate parts of the “old campus,” as it is now known, were scattered among sections of Circular, Regent, Spring, Phila, Clark, White and Court Streets, as well as Union and Nelson Avenues.

But during that same decade, major changes were afoot. In ’61, the board of trustees unanimously accepted trustee J. Erik Jonsson’s gift of 1,000 acres of land to the college, which would serve as the basis for the “new campus,” which took nearly a decade to complete. Designed by Texas architect O’Neil Ford, its signature feature is exposed red brick—a favorite in and around Saratoga—that can be found on buildings such as Starbuck Center, the Filene Music Building and Case Center.

Over the last two decades, Skidmore has zhuzhed Ford’s rather austere design pallet up quite a bit, with additions of the Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery in 2000 and the Judy and Arthur Zankel Hall in 2003, among other upgrades adding design punch to the “new” look. And according to a college rep, one of current Skidmore president Marc Conner’s major goals is to begin a collaborative Campus Master Planning process to help shape and define Skidmore’s campus for decades to come. —Will Levith

Classical Architecture

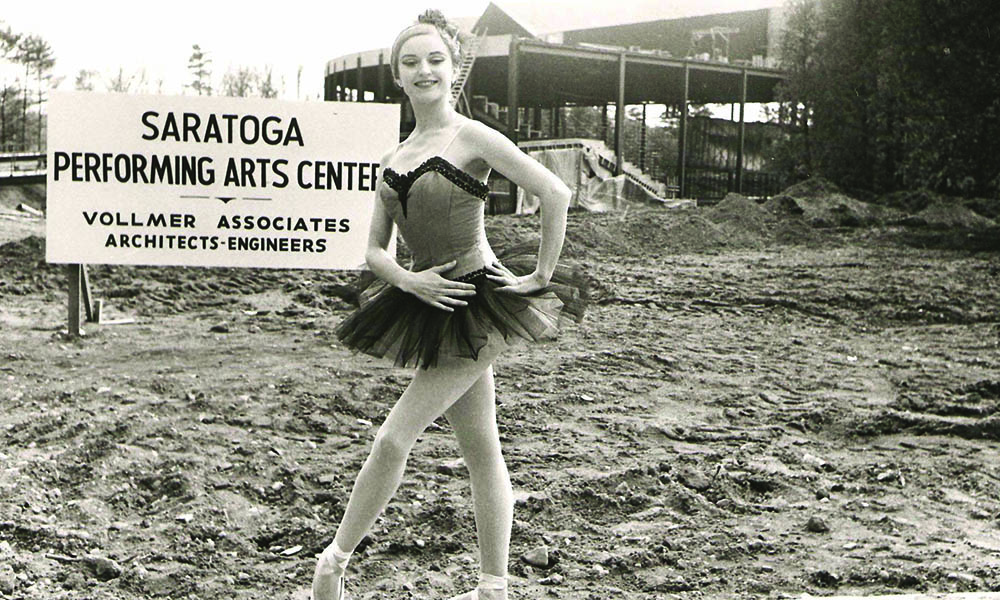

After getting the green light from New York Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller in 1964, New York City–based architecture firm Vollmer Associates started work on the open-air Saratoga Performing Arts Center (SPAC). Robert Loren Rotner, lead architect on the project that was to make the most of its unique setting in Saratoga Spa State Park, told the Albany Times Union that early critics assumed his design “was too open in the sides and back and wouldn’t work acoustically.”

Clearly, the naysayers were wrong. SPAC opened in ’66 to great fanfare, becoming the permanent summer home of the New York City Ballet and Philadelphia Orchestra and eventually the venue Live Nation would rent out for big-name acts such as the Dave Matthews Band, Cardi B and Mumford & Sons.

Even its new additions and upgrades honor the amphitheater’s roots within the 2,400-acre park. Last year, new facilities and an open-air pavilion were erected to maintain its park-like aesthetic while restoring original sight lines.

“It needed to architecturally ‘speak to’ the 1935 neo-Georgian Hall of Springs, as well as to the mid-century modern amphitheater—while also melding in with its natural setting,” Elizabeth Sobol, president and CEO of SPAC, says of the Pines@SPAC project many people haven’t seen yet because of the pandemic. “We’ve been so thrilled to hear people say, ‘It was so well-designed, it feels like it has always been here.’” —Brien Bouyea

Saratoga’s Aesthetic Gatekeepers

How the Spa City strikes A balance between historic racing town and modern Place to be.

By Will Levith

Saratoga’s historic buildings and homes don’t look the way they do by accident. The city depends on a quartet of aesthetic gatekeepers, who sit on its government’s Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA), Planning Board and Design Review Board (DRB), and staff the nonprofit Saratoga Springs Preservation Foundation (SSPF)—with the DRB ultimately making the informed decisions that keep Saratoga looking the way it does. The review process could address anything from the types of signs a downtown business can affix to its facade to the dimensions of an entranceway door on a historic home. Here, two of the main players in the process ring in on why Saratoga’s review process, while irksome to some small businesses and homeowners, is so important to the city’s aesthetic.

Tamie Ehinger, Chair of the Design Review Board

On Keeping Saratoga’s ‘Brand’ Intact

The historic districts in our city are part of the fabric of this community. They’re part of what makes Saratoga special. Historic homes have current owners, they’ve had dozens of owners beforehand, and there will be many afterwards. Current homeowners are “stewards” of the property.

On Mixing in Modernity

What is wonderful about local architects and builders is that they not only understand the city’s design guidelines, but they also embrace them. They live locally—they understand the value of maintaining the historic aspects, nature and character of the city’s buildings.

Samantha Bosshart, Executive Director, Saratoga Springs Preservation Foundation

On the Importance of Historic Preservation

I wish more people knew that the Saratoga Springs Preservation Foundation was here to serve as a resource to the community. The organization’s mission is to preserve the architectural and cultural landscape and heritage of Saratoga Springs. We are always advocating for best preservation practices, and we see ourselves as a resource for property owners. A lot of insensitive changes were made to Broadway’s historic buildings in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. It’s because of the foundation’s involvement and the historic review process that Saratoga looks the way it does today.