Editor’s note: As the Saratoga Springs Preservation Foundation celebrates its 40th anniversary, Saratoga Living looks back at how the city and its citizens worked together to preserve Saratoga’s rich heritage and restore its historic landmarks. In 1917, sculptor Daniel Chester French returned to visit Saratoga and his 1915 masterwork, The Spirit of Life. 100 years later, we revisit the 2015 Trask Memorial Restoration Project with new perspectives.

“We Are Wrecking Congress Hall Hotel,” read the Security Steel & Iron Company’s ad in The Saratogian during November 1912, “and have for sale planks, timber, lumber, windows, doors, sewer pipe, water pipe, gas pipe….” Hoping to purchase the soon-to-be-empty hotel parcel and add it to Congress Park, the village of Saratoga Springs engaged in several years of litigation for unpaid taxes against the owners, the Clement estate. Spencer Trask’s vision for Saratoga as a premiere spa resort hung in the balance. For Saratoga to be competitive with elegant European spa towns like Carlsbad or Baden-Baden entailed more than the ever-flowing healing waters: it required a beautiful city park steps away from mineral baths and lodgings downtown. The hotel’s condition had deteriorated since its bankruptcy in 1904. Mrs. Katrina Trask lamented that “the Park, which should have been a place of green pastures and refreshment,” was instead “capped by the unsightly, dilapidated Congress Hall.”

Aiming to become “the most beautiful spot on the continent,” the village hired eminent landscape architect Charles Warren Leavitt, Jr. in 1912 to map out a landscaping plan for the new and larger Congress Park. The hotel had a sunken rear courtyard in which grew several tall elms. It was Leavitt’s idea to try “to make the most of the natural advantages, the different levels and retaining walls of the Hotel, the trees now in centre court.” In early 1913, three years after Spencer Trask was killed in a train accident, George F. Peabody and Katrina Trask chose a team consisting of sculptor Daniel Chester French and architect Henry Bacon for the Spencer Trask Memorial, by then planned for that northwest park corner. French, Bacon and Leavitt approached the rocky lot as a blank canvas. “They gave us this entirely unimproved plot of ground and permitted [us] to treat it as we saw fit,” French happily recounted; “I flatter myself that the result is sufficient indication of this way of doing things.” The street and lower courtyard levels of the Hotel became the two levels of the Memorial; the courtyard elms remained. It would be August 30, 1913, before the village legally took possession of the parcel for $50,000 less $25,000 in back taxes. The land appeared deceptively clean, for once Security Steel had taken the Hotel down to piles of debris, the village allowed all remaining waste material to be dumped into the cellars.

Jimmy Capobianco, project manager/estimator for Midstate Industries, who acted as general contractor for all on-site 2015 Trask Memorial restoration work except the central pool with its niche and statue, recalls discovering the Congress Hall remains “within the first day… only buried 16 inches below the ground, maybe less in some areas…that definitely put on I would say 25% [in labor hours].” Site Lead JC McCashion recalls, “pretty much seven days a week I was running one of the trucks to keep up” with the need to haul off thousands of rocks and bricks to enable digging trenches for the wiring and sidewalks in time for the 100th Anniversary Dedication on June 26, 2015. The project had been publicly posted for bid by the City with only one response, from Midstate. Much of the 2015 Restoration material — landscape shrubs, concrete, sod, the iron gate to the Arts Council — was donated, which limited profit for the contractor; the nearly $750,000 project required knitting together a complex 50/50 partnership between the City and the Saratoga Springs Preservation Foundation. “We stepped up for Debbie [Assistant City Engineer Deb LaBreche, who managed the project for the City],” Jimmy recalls, citing “other work we’ve done with her, she’s always right there to take care of our needs.” JC remembers, “the schedule overwhelmed everybody, not only ourselves, but the other agencies.”

The idea for the Trask Memorial Restoration first arose in 2010 out of concern for the safety of the memorial under its aging white pines. Samantha Bosshart, executive director of the Saratoga Preservation Foundation, recalls that the scope of the project expanded when “[landscape architect] Martha Lyon’s research showed that Leavitt’s plan was for that whole northwest quadrant.” Martha recalls the complexity of working with Leavitt’s original map, found hidden in City Hall, as “some of the plant species do not exist today… [while] other plant species are invasive and best practice does not condone use of them.” Additionally, several unusual trees near the memorial had been donated to the park by local citizens over the past twenty years: a juneberry, Kentucky yellowwood, star magnolia, eastern redbud, flowering dogwood, purple weeping beech, and Kentucky coffee tree. Most donated trees are given in memoriam; forester Rick Fenton helps to choose and artfully plant these sentimental reminders across the park landscape. Martha kindly incorporated them into the restoration plan.

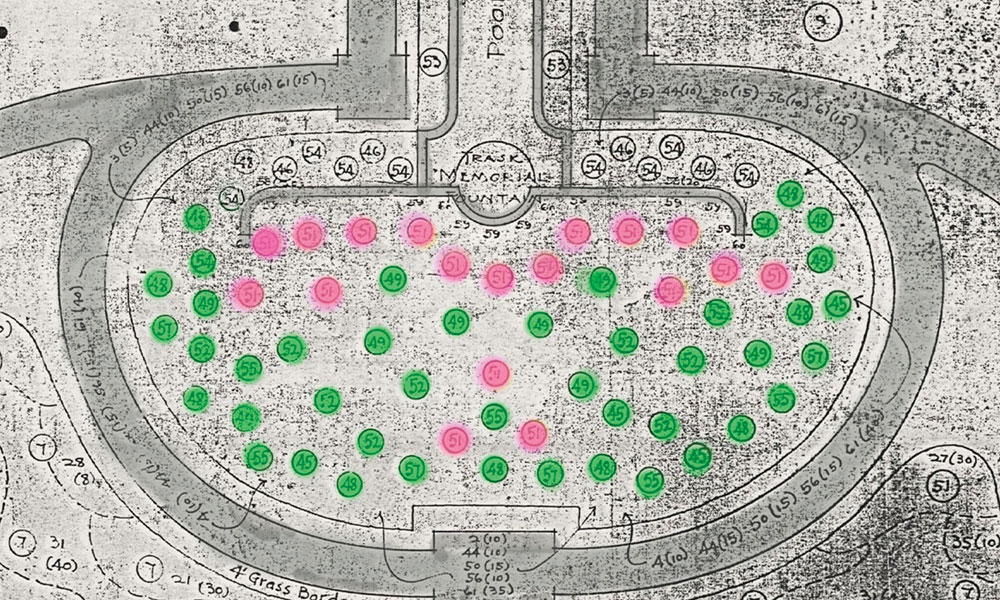

In Leavitt’s day, mature elms formed most of the tree-scape of the park. Elms lined Broadway and Spring Street; a curved row of elms dotted along the brook in front of the Casino; elms encircled the large lawn below the Congress Spring. Their limbless lower trunks and high sprays of curved leafy branches shaded the pond beyond Deer Park Spring so distinctly that it was called “The Shadowing Pool” in Katrina’s memorabilia. Leavitt, French and Bacon planned a radical departure for the tree-scape on the upper level of the Trask Memorial: 59 evergreen trees, spaced irregularly across the oval between the paths. Forty-seven of these trees would mature to 50+ feet: white, Austrian, and scotch pines; blue spruce, and hemlock. The remaining 12 cedars and arborvitae would reach around 25 feet. Eighteen white pines, nearly a third of the total, made a solid row along the top of the masonry wall, thus forming the statue’s visual backdrop. As beautiful and welcoming as is today’s open landscape, this very different historic plan, a “combined effort” of the three designers, is worthy of note — especially in its display of the many-layered ideals cherished by the Ladye of Yaddo, as Katrina Trask was affectionately known. The quest to understand this pocket-sized forest in the heart of downtown Saratoga requires a trip back in time, out Union Avenue to the great Yaddo estate.