Of all the goals people hope to achieve in celebration of their 40th birthdays, Jeff Engler’s is a unique one. The Wright Electric CEO—whose milestone birthday is this month—wants to build the world’s largest electric plane.

The challenges are immense, but Engler must be doing something right: Major backers such as NASA, the US Air Force and easyJet have already lined up behind his buzzy electric aerospace start-up, which recently relocated to Malta. The aviation world is excitingly on the precipice of a green-energy revolution, with first-generation electric commercial planes set to launch in the next few years—and Engler says his company’s planned 100-passenger Wright Spirit will be among them come 2026.

Founded in 2016 and formerly based in Boston and cities in California, the 15-person company set up shop last summer in the woodsy 280-acre Saratoga Technology + Energy Park—the former site of the government-run Malta Test Station, a rocket testing and research facility that is now a haven for various high-tech, clean energy companies.

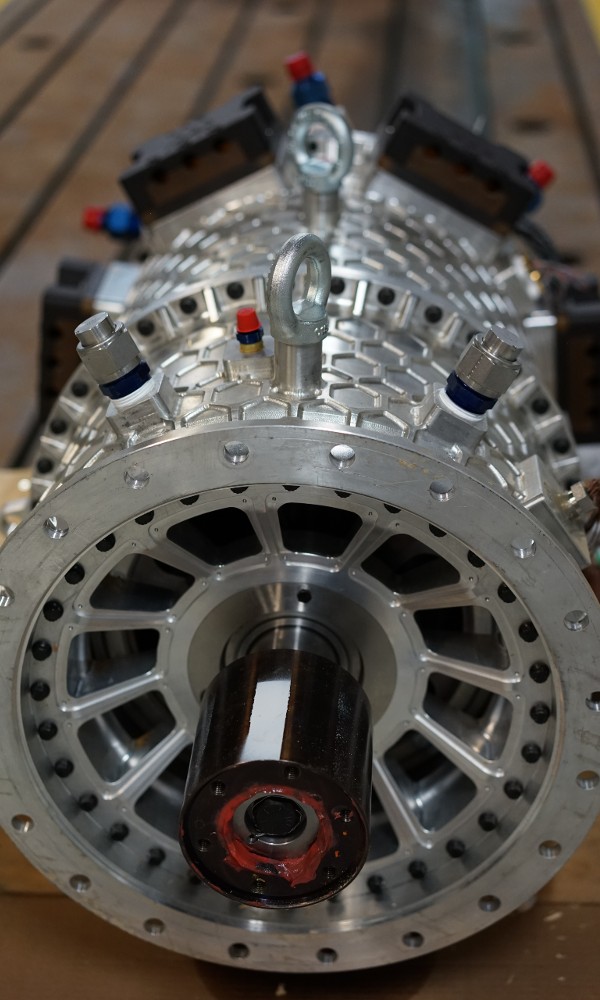

“We make a very specialized motor and a very specialized computer to control that motor, and there aren’t a lot of places in the world where there are people who have deep expertise in that,” Engler says of the talent pool here in Tech Valley, citing the presence of high-tech companies such as GE Research and GlobalFoundries and techy higher-learning institutions like Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. “There are lots and lots of engineers and suppliers and general knowledge through academia, as well. It’s a virtuous cycle.”

Engler seemed destined for a career in sustainable aviation. His grandfather was an aerospace engineer, and his parents were ardent environmentalists who instilled in him a love for the planet and the great outdoors. “I love all the outdoorsy activities in the Capital Region, north and south,” he says. “There’s extraordinary hiking and biking;

the nature in the area is unparalleled.”

After growing up in Westchester, Engler went on to receive an MBA from Harvard Business School before eventually eyeing an online calculator that measures one’s personal carbon footprint. He was so affected by seeing how his shot up with every flight he took that he stopped flying completely for six months. He found that wasn’t a

viable long-term solution in the modern world, but the exercise changed his life.

“What’s already happening with electric vehicles is going to happen with planes, too,” he says. His mission is to eliminate carbon emissions from all flights under 800 miles by the year 2040. In pursuit of that goal, Wright Electric set out to design an emissions-free, electric propulsion system that’s compatible with either batteries or hydrogen fuel cells, which can ultimately convert planes to all-electric power.

With a worsening climate crisis, there’s no time to lose. The aviation sector is behind a billion tons—or about 3 percent—of the world’s annual carbon dioxide emissions, with projections for aviation’s carbon emissions to triple by 2050 without the implementation of sweeping decarbonization measures. While most airlines have agreed to meet the United Nations–set net-zero carbon emissions targets for 2050, in order to avert the worst effects of climate change, those goals can only be successful if fossil fuel–free airplane technologies are developed. Electric aircraft not only serve to eliminate jet fuel emissions, proponents say, but also reduce noise and slash operating costs, too.

Luckily, Wright Electric’s planes are not some far-off fantasy. The company’s first electric aircraft, the 100-passenger Wright Spirit—a retrofitted BAe 146 plane from British aerospace company BAE Systems—is targeted for 2026. The four-engine planes are expected to have a flying range of about one hour, or 400 miles; ground testing on the electric propulsion unit is currently underway, with flight tests expected to follow in 2024.

Engler says there are many advantages to retrofitting an existing plane with electric motors, rather than designing an entirely new aircraft. “Because you’re starting

with an existing airplane,” he says, “you get to market more quickly, and there’s less work to be done.”

All the same, Engler says he has some major hurdles to overcome as well, including a stringent regulatory process to clear with the Federal Aviation Administration. “There’s a lot of technology still to be built, and not just the motors that our company is doing,” he says. “People are working on this technology, and it also needs to be validated and verified.”

And finally, there’s a certain amount of inertia to counter.

“There are a lot of people within the airplane industry who are really happy with existing airplanes, and so we’re sometimes looked at as a disruptive force,” Engler says. “With any new company that comes in with a new technology that has the potential to have

some advantages but disrupts the existing supply chain, you sometimes see headwinds.”

Further out, with a target for the early 2030s, the company is angling for an all-electric new-build commercial plane. Dubbed the Wright 1, it will be designed from scratch, with a 186-passenger capacity and 800-mile range. Engler says that the planes’ designs won’t look much different than standard jet planes, though they will have several more engines underneath each wing.

“It’s kind of like how from the outside a Tesla doesn’t look very different from a regular car,” he says. “But under the hood, it’s quite different.”

Most of Wright Electric’s fellow electric aviation start-ups focus on smaller passenger planes requiring less battery power (such as United’s planned fleet of 19-seat electric planes). But that was never enough for Engler. “We’ve been laser-focused from day one on building technologies to decarbonize airplanes larger than 100 passengers,” he says of the plane size that’s responsible for the vast majority of emissions in the aerospace industry. “Even though, of course, it’s a harder technical challenge and is going to take longer, that’s where the biggest opportunity is for carbon emissions reduction.”

It’s an ambitious strategy that he says has put the company “years ahead of the competition” and has attracted some major government contracts, and partnerships with short-haul behemoths such as the aforementioned easyJet in Europe and Viva Aerobus in Latin America.

For its part, the Capital Region, with its key crossroads location along historical transportation routes, is no stranger to aviation innovation. In 1910, this area gave us America’s first long-distance intercity flight, piloted by Glenn Curtiss between Albany—whose airport was established two years prior as America’s first municipal airport—and New York City. Meanwhile, Schenectady County Airport, now home to the Empire State Aerosciences Museum, was once the site of the General Electric Flight Test Center, which was responsible for major advancements in aviation. Famed American aviators Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart once hopped between these early regional airfields.

Today, the region is once again promising more pioneering work and headline-making achievements in the aviation space. And Engler, who hopes his planes will soon fly out of Albany and other airports, emphasizes that there’s not a moment to waste in launching this new era of electric flight. “With every flight, a little bit more carbon goes into the air,”

he says. “It’s a race against time.”