Back in the days of my romantic, vagabond youth, I set myself a lofty goal: From the bottom point of Louisiana, I’d ride a Felt Z10 road bike, laden with panniers, to Northern Minnesota’s Lake Itasca. Looking at a map, it seemed possible—indeed, anything was possible back then. The plan was simple: follow the mighty Mississippi River from the delta to its headwaters like a modern-day Huck Finn in reverse. I bought the Felt from my friend Alex for a couple hundred dollars (“I wish I’d never gotten rid of it,” he told me recently) and set out on my adventure. I barely made it to Baton Rouge before I heard the news. My mom was sick with the unthinkable: stage 2 breast cancer. I canceled the trip, bought the first ticket home and never looked back.

Legendary framebuilder Ben Serotta knows all about being at a crossroads. As one of the preeminent road-bike framebuilders in the US, he’s had to reinvent himself and his brand several times throughout his four-decades-long career. Along the way, he’s had to make tough choices at critical junctures that, like my decision, were rooted in deeply personal rationales. His Mom is sick, get home was Can I provide a meaningful wage for my family brazing bike joints ten hours a day? For Serotta, what began as a passion for wielding a torch and working with his hands—one literally ignited by his mother—would become Serotta Competition Bicycles, a world-renowned business that, at its peak in 2002, was on its way to selling more than 3000 high-end bicycles per year and generating annual revenues of more than $6 million.

At 65, the trim, congenial Saratoga Springs native is showing no signs of slowing down. That includes riding, which he does almost daily. As a longtime road cyclist, he’s keenly aware of the connection that forms between rider and bike. Some bikes he considers “functional art.” But that doesn’t mean he’s a sentimentalist. “Most people expect that I have a deep collection of bicycles that I’ve made through the ages,” he tells me. “I don’t think I’ve ever owned more than three at a time.” In that regard, Ben Serotta will always be a creator—always looking ahead to the next innovation, the upcoming project. Says Serotta: “I’m far more interested in what the next bike is going to be than the last one.”

But to understand where he’s going, you need to understand where he’s been. Serotta grew up riding bikes through the winding, hilly roads of Saratoga and neighboring Greenfield. Today, the office that he shares with his wife, Marcie, on the outskirts of town, is only two miles—or a short bike ride—from the eclectic hardware store his parents owned in the Collamer Building on Broadway, from which Serotta first started selling bikes. He eventually moved his bike-selling operation to the brick warehouse behind it, where it became a profit-generator in its own right. (Today, restaurant Farmers Hardware occupies the building.)

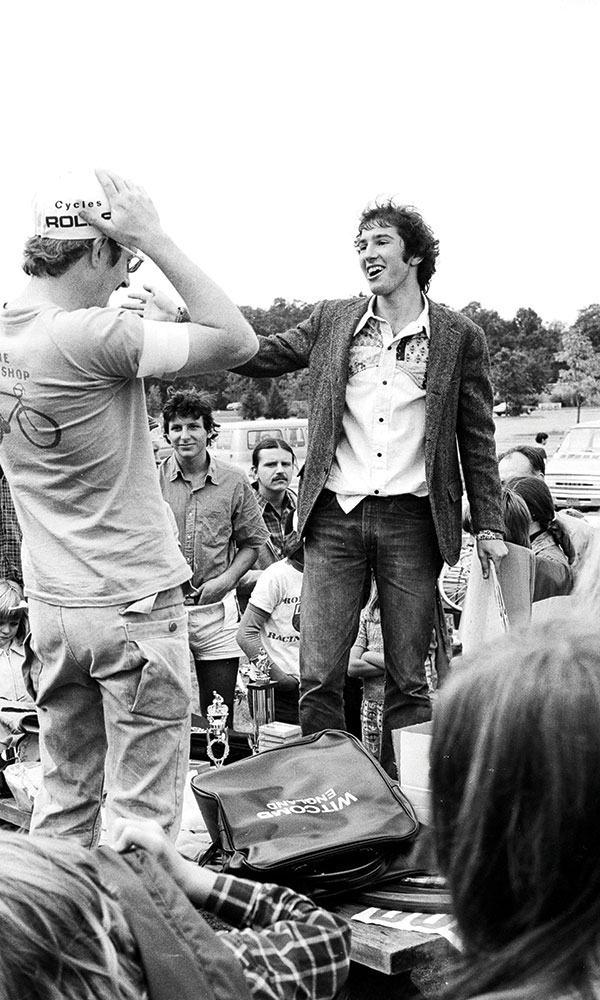

It was around this time that his mother, Caroline, who grew up in the Netherlands and attended Skidmore College, where she trained as a jewelry maker, first introduced her son to an oxy-acetylene torch. Immediately he was hooked, the glowing rosebud tip giving his precocious mind creative carte blanche to run wild. In the fall of 1971, having completed his high school credits six months early, Serotta somehow convinced his high school administration to grant him a leave of absence for the final semester of his senior year. The 17-year-old landed at Witcomb Lightweight Cycles in London, an artisanal shop specializing in custom, handmade steel bicycle frames. It was there, in a dimly lit, Dickensian workshop, that Serotta would learn the art of framebuilding.

Eventually returning home to Saratoga, Serotta set to work designing a classic high-performance racing bike—the first he’d ever build on his own. “The best size of any bike I’ve ever built is my own,” says Serotta, chuckling. A little sheepishly, Serotta opens up about his rapid ascension throughout the ’80s and ’90s, a stretch of time that would see his two daughters, Anna and Emily, born—a deciding factor in his decision to transition from successful solo builder to large-scale business owner focused on the mass production of custom-fit bikes. By the mid ’90s, the Serotta factory in Saratoga employed more than 50 craftsmen and built more than a dozen frames a day, some that would go on to be ridden in the Olympic Games and the Tour De France.

Looking back, Serotta admits he made some miscalculations in that business decision—a crucial one being when Serotta Competition Bicycles doubled down, becoming an almost exclusive custom-fit manufacturer. The frames were also made in the USA at a time when, it seemed, all the American and EU bike manufacturers were outsourcing almost entirely to Asia. Serotta’s business model—relying on sales through an established dealer network, which caused long wait times between orders and delivery—also created cash flow problems. To compound the issue, an economic downturn was making high-end luxury items—such as $10,000 road bikes—unpalatable for even the most dedicated riders.

In 2013, about a decade following the company’s apex in the early aughts, Serotta parted ways with the company he’d worked so hard to found. Shortly afterwards, in what must’ve been of little consolation, the company shuttered. What was once the Serotta factory has been acquired by local developer Ryen VanHall, and has housed Upstate Distilling Company and microbrewery Artisanal Brew Works for the last three years. And no, he’s never had the urge to stop in for a pint and wax nostalgic about the old days. That’s not the Serotta way.

But as they say, absence makes the heart grow fonder. In 2015, Serotta found himself reenergized when he was brought on as a consultant by New York City’s Citi Bike program. Then, in 2017, when he was splitting time between two workshops—owned by “Frank The Welder” Wadelton in Bellows Falls, VT, and Carl Schlemowitz in New Paltz, NY—he quietly but resolutely started building a new line of fully customized, made-to-order, steel-frame bikes, using everything he learned about weight and fit over the preceding decades. He named the line aModoMio, Italian for “My Way.” Since then, he’s withdrawn from the day-to-day—but only slightly. While the aModoMio C17 model was built by Serotta’s hands alone, the C18s and C19s have been constructed with the help of a familiar team: Wadelton and Schlemowitz. Serotta quips that his position in the newly formed Serotta Design Studio is “Designer-in-Chief.”

At first glance, it would appear that Serotta’s come full circle, but with one major change: He’s not putting resources into a manufacturing facility. Instead, he’s working with multiple companies “on the cutting-edge of materials and technology,” he says, such as 3-D printing—way beyond the range of any of the companies in the bike manufacturing industry, as far as he’s aware. One of the beneficiaries of this new process is the Duetti model, an aluminum bike in 11 sizes that he’s outsourced to an overseas factory. Up next, two new models that will be available in multiple specs: go-anywhere, adventure-ready road bikes with clearance for larger tires that are designed to handle whatever combinations the road throws at bikers: dirt, gravel or well-packed trail.

When I hear Serotta talking about such hardscrabble roadways, it’s difficult for me not to draw an analogy between them and his career. Life has thrown a hell of a lot of curves and combinations at him, but the Saratoga native just keeps his head down, methodically churning. “I thrive on getting out of bed and not revisiting what I’ve already done, but opening the next doorway, doing something a bit new and a bit different,” says Serotta.

Maybe I need to revisit that bike trip after all.

Lock, Stock and Beryl

It shouldn’t make sense: The pioneering manufacturer of custom-fit road bikes, tailored to discerning individuals, partnering with a bike share company that caters its products to the masses. (Especially when you consider that the average road-style bike is about 14 lbs., while the average urban bike share bike is about 50.) Then again, who better to put all their experience into personalizing a single bike for a wide range of body types than framebuilder extraordinaire Ben Serotta?

After working briefly on NYC’s Citi Bikes, Serotta’s now linked up with Beryl, London’s bike share program. Once again working as a design consultant, Serotta kicked things off “much the same way I would start a single bike project,” he says. “We got to know a cross-section of the people who we were hoping would be riding these bikes.” Beryl’s program will launch in Bournemouth and Poole, both in England, this spring; by the summer of 2019, the company will have put more than 1000 bikes on the streets, with a plan to launch in Northeast London down the line.

When asked what makes bike share programs tick, Serotta says: “Riding’s a great way to start and finish a work day, getting a little bit of exercise and a little bit of freedom.”